Eley Williams on Classic Ghost Stories and Goodnight Moon as Avant-Garde Horror

Book Recommendations From the Author of The Liar's Dictionary

Welcome to the Book Marks Questionnaire, where we ask authors questions about the books that have shaped them.

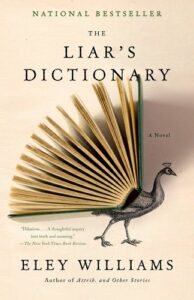

This week, we spoke to the author of The Liar’s Dictionary (out now in paperback), Eley Williams.

*

Book Marks: Favorite re-read?

Eley Williams: I return to books far less frequently than I used to—this is bound up with boring beleaguered reasons related to shot-to-hell attention spans, a self-imposed pressure to “keep up” with new releases, and excuses I persist in making about not having the time. Rereading a favorite book is one of life’s great pleasures—even if the second or third read means the book’s initial dazzle wanes or abrades. That said, there’s nothing waning about Ali Smith’s collection The First Person And Other Stories (2008), which is on what feels like a constant rotation in my house and in my head. There is comfort to returning to its stories, but a thrill too. She is a writer who can do wit and devastation and placidity within a paragraph.

Perhaps the key to the appeal of Smith’s writing for me originally was the attention she paid: to details of language, incidence, literary conventions. Myths collapse into song lyrics; hauntings surge into literary criticism of a shadow; an anecdote about an accordion becomes a soul-clenching portrait of a relationship honing, tuning, refining. Honestly, something for every mood, in every sentence, in every story. It’s a queer and honest and radical and funny and fraught collection, and I love it as much as when I first gulped it down. I’m going to go and read it again right now.

BM: What book do you think your book is most in conversation with?

EW: In my naivety, I suppose I thought that ‘fictional portrayals of lexicography’ might be a pretty roomy niche for my book to occupy—far from the case. The Liar’s Dictionary first came out in the UK in 2020, the same year as Pip Williams’ hugely popular and critically acclaimed work of historical fiction The Dictionary of Lost Words. Both of our books deal with themes of discrepancies and strangenesses related to language, and specifically the cultural and social institutions that can either shape, use or actively oppress the way words are codified not least as related to gender, class and other structures. Both examine individuals’ complicity in these structures, and also quirks of happenstance related to dictionaries’ composition, and the human, tender ambivalence that can surround aspects of characters being in language’s thrall.

Pip Williams’ novel uses close research of source material directly related to the real Oxford English Dictionary, while mine goes a little madcap with a similar-but-different, entirely fictitious compendium of words; however, we both clearly relied on some shared secondary scholarship and certainly fell down shared rabbit-holes of research. It’s wonderful to think that our two very different books might be read alongside one another—and the fact we have shared surnames, and a prominent character in my novel is called ‘Pip’? An enjoyably uncanny fractal pattern of connections between the two novels.

BM: A book that blew your mind?

EW: A short, smart and smarting work of non-fiction, I feel like So Mayer’s A Nazi Word for a Nazi Thing (2020) should be on every syllabus that considers curation, “gatekeeping,” cultural history, literary experiment and notions of editorial probity. I learned a hell of a lot, both about the book’s subjects but also how to communicate research: Mayer riffs upon and examines connections between totalitarian regimes and defiant artistic expression, with considerations of shame, pomp, and state violence. It’s riotous and scintillating scholarship by a writer who makes theory and critique an active, generous, nuanced moment of activism. Highly recommended.

BM: Last book you read?

EW: With Hallowe’en just gone, I have been swigging at an anthology of M.R. James ghost stories. There is much to enjoy there, both in terms of the quasi-kitsch of some of the stories’ framing devices, and the genuinely, palpably unsettling dread he can instill. Come for the bumbling academics and dusty seaside resorts, stay for the matted, fetid glimpses of an unnameable curse etc. I swear the population of spiders in my house tripled between my starting the anthology and my closing the covers, and the walls of my room now creak with a perceptibly ominous cadence. I see that there will be a BBC TV adaptation of “The Mezzotint” this Christmas—something to look forward to/new visualizations of horridness, forthcoming.

BM: What book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

EW: I was very pleased to see that Golem Girl: A Memoir by US-based writer Riva Lehrer was the winner of this year’s Barbellion Prize in the UK, a new award “dedicated to the furtherance of ill and disabled voices in writing.” Lehrer’s memoir is a complex and rousing account of her life, written with candour, zest, and clarity about lives and of the notion of portraiture generally. I have read few books that access and share accounts of vulnerability, desire and artfulness so well: I’m thankful for its place on my bookshelves.

BM: Favorite book to give as a gift?

EW: I’ve been giving copies of Lavinia Greenlaw’s Some Answers Without Questions to friends in recent months; a book that’s difficult to define, but then sometimes the best gifts are never wholly simple things. In many ways it is a memoir, but also a polemic, but also a keepsake about difficulty and exhaustion, but also a demonstration against them. It helped me recognise and take solace in attempts to find a voice or energy in times of alarm or disjuncture, and I hope handing it to others might do the same.

BM: Classic book you hate?

EW: The book is, I’m sure, wonderful. I’m convinced it is. I am told it is rounded, philosophic, funny, radical, dynamic, aching, searching, sublime. I fully admit that the fact I cannot get past the first couple of pages despite trying my best means I am the problem—I am flatness itself, with the intellectual capacity of a dusty sock and potentially the absence of a soul, a coward!, but: I swear I can feel my brain desiccate every time I read the first page of Anna Karenina. I will get over this. I will.

BM: What’s a book with a really great sex scene?

EW: Francis Ponge’s description of an orange in Le parti pris des choses goes there, doesn’t it. Or the scene in Ali Smith’s Girl Meets Boy, where the full stops leave the page. Apparently prose-poetry comes to mind, which probably says something either very revealing or uncertain.

BM: Favorite children’s book?

EW: Difficult to answer this and not think of how my perception of “children’s book” has shifted recently. For the history of children’s picture books, I really must first recommend Clare Pollard’s recent non-fiction Fierce Bad Rabbits. I have a 9-month-old son, and I am inexorably, not-unenjoyably going around the bend reading Goodnight Moon to him with my wife every night before bed. I’m agog and aghast by it every time: it’s like an avant-garde horror narrative. Why is there a bowlful mush? Who is the old lady whispering “Hush!” who seems to flit in and out of existence in the corner of the room? Why are the bears in the picture on an early page all staring at each other, paws folded, like they are in a group therapy or a mob-boss debriefing? WHAT DO YOU MEAN, “GOODNIGHT NOISES EVERYWHERE?”—Goodnight Moon seems to enact the scrabbling anti-logic of falling asleep perfectly, and I love-hate it.

I can’t wait until my son’s old enough to read The Wind in the Willows, which I think has just the right amount of balance between Edwardian tweedy social drama among woodland creatures alongside completely batshit incursions about a small god Pan noodling in the faux idyll of an imagined English countryside. Sweet, brooding, excoriating, with cross-dressing toads and, I’m told, a fictional representation of a famous dictionary editor (the character Ratty sharing much in common with the very real Frederick Furnivall, with whom Kenneth Graham was acquainted): one to re-savour when we get there.

Personally, I loved the Redwall books when I was growing up, and blame them for a brief but thoughtful stint studying theology as an undergraduate. Eulalia.

BM: Book you wish would be adapted for a film/tv show?

EW: I think that the stories of Saki (H. H. Munro) would make for very compelling viewing, and their mix of satire, horror, comedies-of-manners and campiness would translate well to television in the right hands. I suspect I would not have liked Saki the man, but the bitter, awful, and horribly funny world of his stories seems ripe for adaptation. James Norton as Clovis? Olivia Coleman expounding upon the Schartz-Metterklume method? Timothee Chamalet as Gabriel-Ernest? I believe the poet and writer Timothy Thornton once posited developing some stories into a series of stages operas: here’s hoping.

*

Eley Williams is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. She is the author of Attrib. and Other Stories, and her work has appeared in The Penguin Book of the Contemporary British Short Story, Liberating the Canon, The Times Literary Supplement, and London Review of Books. She lives in London.

Eley Williams’ The Liar’s Dictionary is out in paperback from Anchor Books

*

Book Marks

Visit Book Marks, Lit Hub's home for book reviews, at https://bookmarks.reviews/ or on social media at @bookmarksreads.