Eleanor Shearer on Migrants in Hiding and a Caribbean History of Canada

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

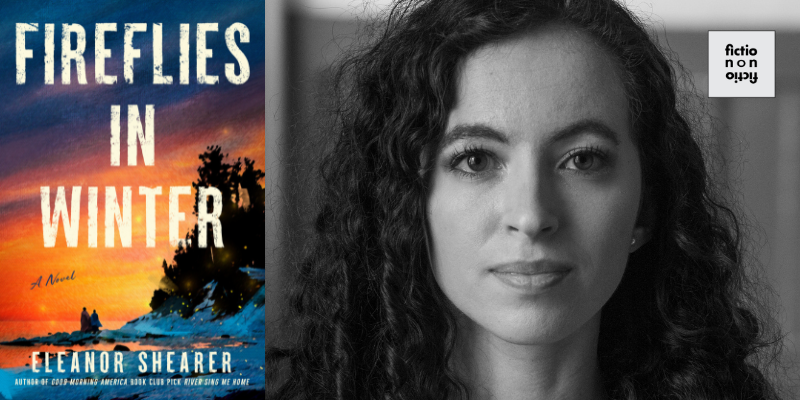

Novelist Eleanor Shearer joins co-hosts V.V. Ganeshananthan and Whitney Terrell to discuss her new novel, Fireflies in Winter, which depicts the little-known history of how the Leeward Maroons of Jamaica—a free Black community descended from formerly enslaved Africans and indigenous people—came to Nova Scotia at the end of the 18th century. Shearer, who is British and has Caribbean ancestry, explains the genesis of her interest in the Maroons as an example of successful resistance to slavery, since they fought the British in Jamaica, but also a kind of collusion with it, as they captured and returned runaway slaves to plantations there. She reflects on the connections between her Black heroines’ precarious situation in historic Canada and the situation of immigrants in the U.S. and elsewhere today. She also considers her research process, depicting queer life in earlier periods, the importance of sensory and embodied detail in historical writing, and her choice to write about the past in the present tense. Shearer reads from Fireflies in Winter.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan and Whitney Terrell.

Fireflies in Winter • River Sing Me Home • ‘Rebranded plantations’: how empire shaped luxury Caribbean tourism | Slavery | The Guardian

Others

Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery • Davos 2026: Special address by Mark Carney, PM of Canada | World Economic Forum • Prime Minister Carney delivers remarks at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting • Black Loyalist Heritage Center, Nova Scotia • Carrefour Atlantic Emporium Bookstore • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 8, Episode 22: Suzette Mayr and Kai Thomas on Canada Versus Trump

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH ELEANOR SHEARER

Whitney Terrell: So, Cora and Agnes and Thursday are not the only people in this story. Cora lives with Silas and his son Benjamin. I wonder if you could give us, our listeners, and hopefully future readers, an outline of the structure of the book, and talk about those characters and what Cora’s relationship is to them and how they’re getting on as the novel goes.

Eleanor Shearer: In many ways, this is a grief book as well as a book about freedom, because Cora is grieving for the home that she lost in Jamaica, but she’s also grieving for a close friend in Jamaica. They grew up together, but then this woman married this man, Silas, who’s a captain in the Maroons. The structure of Maroon society is very martial. I mentioned earlier that they form patrols and militias to keep the plantation system in Jamaica in order. So, many of the men are doing military service. It’s probably also worth mentioning that, although it’s not made explicit so much in the novel, it was also a polygamous community. It’s very possible that Silas emerges as a threat to Cora in terms of possibly being forced to marry him. It’s possible that that’s something that could have been seeded even back in Jamaica, when he had his first wife, Elsie, who was Cora’s friend, because he would have been allowed to marry both of them.

Benjamin is the son of Cora’s friend who died in the war that was fought just before the Maroons were exiled, and Cora herself is an orphan. She doesn’t remember either of her parents, and so she occupies this slightly ambiguous position within the community that Silas, at points, exploits to have power over her. And the Maroon characters are not just Silas and Benjamin, but Cora has got her adopted mother, Leah, as well. I wanted to flesh out these different relationships, not all of them good, not all of them bad, and give a sense of the contrast between the sort of quote, “civilized world,” the world of community and people and family ties, or friend ties that Cora exists in Preston—which is where the Maroons settled in Nova Scotia— versus the world of the wilderness that Agnes pulls her out into.

Agnes is living there by herself. The ideas in the novel are about freedom, but also about sexuality. This is a queer love story at a time when it wouldn’t have been safe to be queer, and so there are questions of, where are you most free? I don’t want to sugarcoat the idea of living by yourself in the wilderness. The natural world is not purely benign in this novel. It threatens the characters at multiple points. In some senses, you know, being embedded in community, that’s real freedom, because you have people around you to support you. But also, especially if you are queer, like these characters, living by yourselves in the wilderness brings a different kind of freedom. Setting up that social world is a way of then setting up the choices that Cora has to make in the novel, around where can she be most herself? And where can she be most free?

V.V. Ganeshananthan: Whitney mentioned some of the other characters. I love Thursday, I find Silas frustrating, and I have a huge soft spot for Benjamin, who is one of the book’s kids. The book does a really beautiful job of showing the subtle and long term challenges for children of displacement, migration, violence—being in hiding or living at the edge of legal precarity for these very young children. And Benjamin’s not the only child who appears in the book.

I’ve been seeing versions of this in Minnesota where children are, say, separated from their parents, as ICE arrests, detains and deports people. If the families are able to stay together, the experience, of course, impacts the children severely. If the children are separated from their parents, they may not understand what’s happening, or their understanding of how time is moving for them, or if their parent might come back. Benjamin reminded me of all of that, and I was thinking about, in your book, the question of how best to protect and support children in those situations divides people. They don’t agree, and it puts them at different kinds of risk. Can you talk a little bit about putting children in this story, why that was important to include, and about writing about Benjamin?

ES: I think I like to have children in my novels where I can sense continuity through the generations. Especially coming from a Caribbean context where family is so fraught a subject—and actually one of the big things that comes out from my own family experience, as well as some of the research that I did when I was speaking to people in the Caribbean about the legacy of slavery, was a sense that the fracturing of families, which was something that was so common in the period of enslavement, really continues to echo through this day.

What you were saying about some of the more brutal examples of it in America today reminds me of—although this is different because it involved some level of agency or choice on behalf of migrants in the Caribbean—some of the most heartbreaking stories of the Windrush Generation. I’m not familiar with any of it happening in my family in particular but there are these people called The Barrel Children. This would be where a parent would travel from the Caribbean to England, and they would leave children, often young children, behind with some sense that maybe once they were settled, they would be able to send for them. In the meantime, they would send barrels of food and supplies back to grandparents, aunts and uncles, who were looking after these kids. You do have these stories of people who might have had their mother leave when they were four years old, and then suddenly they’re called to England when they’re fifteen. They’re leaving behind their primary caretakers to go and be with someone that they effectively don’t know. That’s to say that there are lots of examples from Caribbean history that informed the way that I wanted to write about children and about Benjamin in particular.

The other thing to say is that I mentioned this is, in some ways, a grief book. Benjamin’s mother has obviously just died, and I, unfortunately, experienced a bereavement recently in my own life that’s been sending me into reading about lots of things to do with grief. The thing about grief and young children is the resilience that often children can learn quite quickly to express normality—they might seem to be playing, they might not express grief in the way that adults do, which makes adults feel like they’re so resilient they bounce back from this big loss, that it’s not taken very long for them to come to terms with the fact that a parent is missing, or a sibling is missing, or someone else significant is missing—but often underneath that, there is huge trauma that obviously shapes the outcome of their life. So that was probably going into writing little Benjamin, to some extent. This is someone who’s experienced this extraordinary uprooting and loss, not just of his home, but of his mother. He might, on the surface, seem quite resilient about it, but there are moments where you can see the hurt shining through.

You mentioned the decisions of the adults around him, of how to process that grief. There’s an early scene where Benjamin says to Cora that he’s seen his mother who’s dead, and then Cora almost wants to have a conversation about that, to understand what is going on, that he’s having a vision of his mother. But his father, Silas comes in and shuts it down immediately like “Your mom’s dead. That’s not possible.” There’s a lot to unpack in terms of how children, specifically, might relate to this. And I do think it was rooted in a sense of past and present. There’s so much upheaval in the real world for children that is so unbelievably tragic and leaves so many lasting marks.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy.

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.