Edwidge Danticat on Haiti and Trump, Past and Present

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

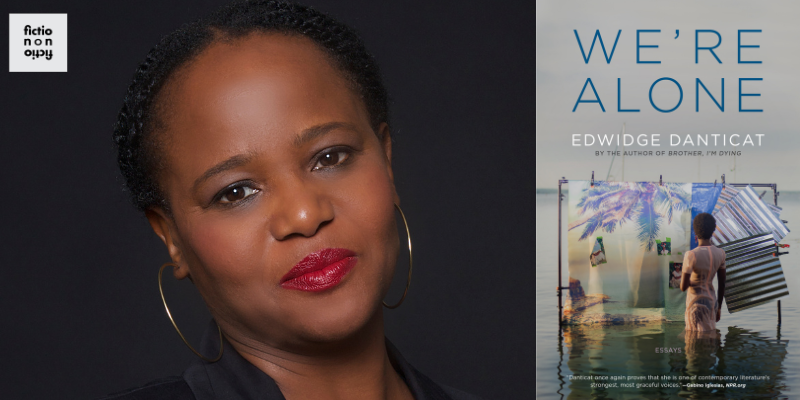

Acclaimed fiction writer and essayist Edwidge Danticat joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss her new essay collection We’re Alone. Danticat reflects on misinformation and xenophobic rhetoric, such as Trump’s false 2024 debate claim about Haitian immigrants eating pets in Springfield, Ohio, and how that type of language and propaganda has broadened during Trump’s second term to include even more immigrant communities. She recounts what she has learned about conditions in prisons and detention centers during her visits there and also considers today’s immigration policies, including the Trump administration’s attempts to end Temporary Protected Status for Haitian immigrants and how deliberately humiliating immigrants not only hurts them, but also deters others considering crossing borders. Danticat describes her connection to Haiti and the ways natural disasters can unexpectedly bring people together as well as how these disasters are tied to migration. She reflects on political instability in Haiti, the meaning behind the title of her new book, and how writers like Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, Jean Rhys and Paule Marshall shaped her thinking and writing process. Danticat reads from We’re Alone.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/ This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, Amelia Fisher, Victoria Freisner, Wil Lasater, and S E Walker.

We’re Alone • Create Dangerously • Breath, Eyes, Memory • Brother, I’m Dying

Others:

Jamaica kincaid (@virtuouspomona) • Rootedness: The Ancestor as Foundation | Black Women Writers (1950-1980) • The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde • Dany Laferrière • Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys • Immigrants can have ponies | Seinfeld (1989)

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH EDWIDGE DANTICAT

Whitney Terrell: One of the things that I really enjoy about your book is this bringing back of history and reminding us of things that we now forget that the American government has done. To me, there are echoes of the current administration all the time. So when Trump talks about invading Greenland, it’s not a new idea. And that “Before” you’re talking about is a Before of many kinds of Before, not just Hurricane Before, but before invasions, like the invasion of Grenada or before colonialism.

Edwidge Danticat: There’s the nostalgia of the exile or the immigrant, that looking back. My parents used to always talk about Haiti in this very conflicting way that didn’t make sense until I was much older. So they would say, “Oh my gosh. This was always so beautiful. This was this moment, we used to stroll…” They would describe these very pastoral scenes that remind me a little bit of that Seinfeld, where the immigrants are describing, “we had ponies.” And George Costanza is like, “Why did you come here then?” So it was this idyllic vision in their minds, but it was only contrasting to the present, to which they would then prevent their children from even wanting to go and see because they’re like, “Oh, it’s too dangerous.” At the same time, they’re like, “It’s so great.” So we grew up with those perimeters.

This idea of Before, which is sometimes very unfair to the present, because it’s just stagnant and stuck in your mind in a certain way, that’s really what I was thinking about. Elsewhere in the book I mentioned where Audre Lorde says—and it’s something I cling to—you mentioned the present… I think every day about where she says, there are no new pains. To paraphrase, we’ve experienced them already, different variations of things, and sometimes in our sadness and anger and despair, I think it’s worth remembering that we’ve been through things like this before.

WT: Speaking of things we’ve been through before, although not me personally, since I live in Kansas City, Missouri, and we don’t have a hurricane season, but we are entering the hurricane season in both the U.S. and Haiti and your essay, “Rainbow In The Sky” talks about a sort of “kinship” to hurricane survivors in Miami because of your prior experiences with them. We’ve talked a lot about the divisions between America and Haitian societies, but here in disaster, you seem like you find a point of connection. Could you expand on that?

ED: Oh, absolutely. I spent most of my childhood in New York after coming from Haiti at twelve, and then moved to Miami in 2002. I lived there for over 20 years, and I remember my first big hurricane summer was Katrina. That was a big summer of hurricanes. Then the next big one was when we had Maria. I remember people joking because that summer, it was the one with Dominica, where they had Maria and Joseph, and then people were like, “Jesus is next.” But yes, that vulnerability, especially in some coastal towns. There was this moment where people were finding items that were marked from Haiti and from the Dominican Republic in the Carolinas, that were washing up on the beach, which also shows this common vulnerability.

And I remember during Katrina, especially, because we had to leave our house, we had to go stay with some other people, because my daughter was really little and I would be watching the news and all the —to the one, and I wrote another essay about it, in another book of essays, Create Dangerously—all the news anchors were going “Why?” Because they were watching the bodies floating, the lack of aid, the desperation in New Orleans, and they were like, “This is not Haiti. This is not Africa”—as if Africa is a country—to say, “Oh, we should be above that. These things only happen in those places.” Really, overemphasizing that when nature was saying, “Yeah, we’re all connected in this way. We’re all like, equally vulnerable.” And I remember when I was living in Florida, you count down to like November 1, which is technically when it’s done. But the trick of these hurricanes—people have been lucky these last few years—but sometimes it could be early October, and you have your home for a week due to a hurricane. So if we believe in extreme weather or climate change, which I do, you have to believe the vulnerability. And I think there’s so many ways that that’s also connected to migration. Because if a place is devastated by nature, of course, then the people who live there, who survive that devastation, will be looking for other places to go, move to. So these things are certainly interconnected.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: Of course, if we’re talking about climate change as a reason for migration, often that’s paired with things like political instability. You have an essay titled “Chronicles of a Death Foretold” and in that essay, you’re describing the political instability of Haiti during the time in which Juvenal Moise was in power and was subsequently murdered. I wonder if you could walk us through the aftermath of that assassination on both the personal level and the public level.

ED: The book opens in 2018 when I’m in Haiti with my family, as we were many almost every summer. And there was a soccer game in Brazil is like the, the sort of honorary, but even more so, like stronger than that team of and then soccer team of Haiti like Brazil Argentina, like, like fans on both sides and that after that game, they were these measures announced, like the price of gasoline went up, and so that started a whole series of protests that then resulted. And there was some money that Haiti had been loaned from Venezuela paid through a fund called PetroCaribe. So there were young people rising up and asking about that money. And then there’s something called peyi lòk, where the country was almost in lockdown for months and months at a time. So there was a surge of activism, yes, against President Jovenel Moïse, but going back to his predecessor, President Martelly, and people were really frustrated, and then the assassination happened which then left—we had a rise in armed groups even then. There were political assassinations, including of a really famous feminist young woman who was an activist. And they were crimes at that time. But after the assassination, there became a larger void, and I think many different parties, including the armed groups which then consolidated their power, drove out the Prime Minister who had succeeded the president. So now there’s a nine-person Council, which was supposed to have held elections next February, but it doesn’t look like that will happen. And then there’s a UN resolution that was just passed to create a force, that just happened, very recently, but there’s been some Kenyans there, which hasn’t changed much of the situation, because the armed groups have coalesced into this coalition.

So it’s really a struggle for—so many people, including family members of mine, have been in the last two years, in four different locations, because the neighborhoods get taken over by these armed groups. It’s a very difficult situation, and it’s very hard to see exactly what’s on the horizon. On the side of hope, it’s in the individuals, like on the ground, the people who refuse to leave who are—you know, I’m on a panel for a that’s looking at art projects to be like, “Oh, in the middle of all that I’m describing, they’re like these artists. They’re these feminists. There are these activists.” There are people who really want to see the country move forward, but they’re caught between this construction of leadership that was almost formed by the international community that’s at the head of the country, and then the armed groups that have so much power. So it’s a very difficult situation.

WT: I want to circle around to the title of the collection, We’re Alone. And in the preface, you talk about that this can be viewed in two ways. One is that we’re alone and no one’s coming to save us. The other being that the writer writes alone, the reader reads alone, but they are alone together. In what ways have writers like Toni Morrison and Paul Marshall influenced this idea to you of being alone together in your writing?

ED: I was an extremely shy child in a family of very vivacious oral storytellers. Finally, when someone gave me a book, I was like, “Oh, thank God. Like, I can just go in the corner with that and be by myself.” I was so relieved that there was another way of being a storyteller than to stand in front of a bunch of people and recite a story. I’ve always treasured that intimacy as a reader and then I realized that also you have, as a writer, because you’re alone, being alone with the book, it’s one of these rare pleasures where you’re just immersed and lost in a story. So I read those writers: Paul Marshall, Toni, Morrison, James Baldwin, Haitian, writers like Marie Vieux Chauvet and others I adore. I just read them by myself in a corner. I felt like, in that moment, they were my own.

There’s a Haitian writer, Dany Laferrière. He’s a Haitian-Canadian writer. Now he’s on the Académie française in France. But he tells the story of his childhood, of being in Petit-Goâve, which is a small town in Haiti. And he says, growing up, he thought Shakespeare was a Haitian writer, Sophocles was a Haitian writer. He says, “Otherwise, what were they doing in my room?” He had this whole nation of repatriating the writers. I feel like maybe I intimatesize—if that’s a word to invent—I draw them in intimately. And then it can also be flipped as a writer, because sometimes when I read something very daring and intimate that someone writes about themselves, it feels like I’m alone with them. And none of us are the same people we are on the page, right? But when I meet them and they’re nice to me, that’s even extra. “I love you. I love you.” I’m not effusive that way, but I’m screaming it in my mind. If they’re kind, I just find it amazing, like it’s an extension of the book. It’s not necessary. I don’t put that kind of pressure on anyone, but the fact that these women were kind to me, including Nikki to Giovanni who passed away recently, is something of another time. There are so many ways now that you people can pre-know you online, whereas back in those days, your first encounter was on the page or in person. So I think there was something about that too where you were really face to face for the first time, as opposed to having been communicating through some other indirect way, or getting an impression of that person.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy. Photograph of Edwidge Danticat by Lynn Savarese.

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.