Edward Gorey's "Great Simple Theory About Art" is essential reading for writers.

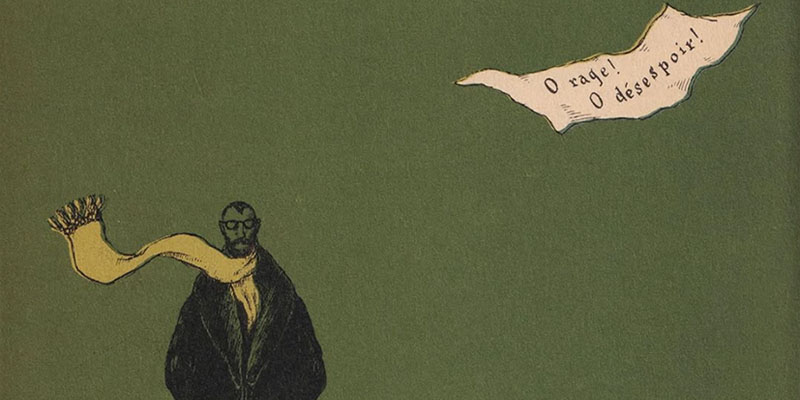

“Many of Edward Gorey’s most fervent devotees,” Stephen Schiff wrote in a profile of the artist in The New Yorker in 1992, “think he’s (a) English and (b) dead. Actually, he has never so much as visited either place.” Alas, he has now visited at least one: Gorey—born nearly a century ago, on February 22, 1925—died in 2000, leaving behind a vast catalogue of work—the macabre, deadpan, funny and sometimes brutal illustrations and short narratives for which he has become a cult icon—and a mysterious personal legacy.

It’s always tempting to try to “figure out” what makes a weird genius like Gorey tick, and I doubt the world ever will. But in Mark Dery’s biography of Gorey, Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey, I recently came across a hint. In one of his many letters to his friend and collaborator Peter Neumeyer—collected, by the way, in Floating Worlds: The Letters of Edward Gorey & Peter F. Neumeyer— Gorey shares what he calls “E. Gorey’s Great Simple Theory About Art,” which Dery notes is “as revealing a statement of his aesthetic philosophy as we’re ever going to get.”

It is, according to Gorey, “the theory . . . that anything that is art . . . is presumably about some certain thing, but is really always about something else, and it’s no good having one without the other, because if you just have the something it is boring and if you just have the something else it’s irritating.”

“E. Gorey’s Great Simple Theory About Art isn’t so simple,” Dery writes.

It owes something to his Taoist rejection of the either/or epistemology of Western philosophy. And to his Derridean-Beckettian awareness of the limits of language. And to his Asian-Barthesian belief in the importance of ambiguity and paradox as spaces where readers can play with a text, making their own meanings. And to his surrealist sense that ‘there is another world, but it is in this one’ (Paul Éluard). Yet above and beyond all that, there’s still something mysterious in his Great Simple Theory, an elusive idea or maybe just an inexpressibly quality that’s more than the sum of these philosophical parts. In a postcard to Neumeyer, Gorey quotes Plato’s Gorgias: ‘There is no truth; if there were, it could not be known; if known, it could not be communicated.’

But technically it’s simple. Look how few lines it takes up. And Gorey liked this kind of non-simple simplicity, as his own work makes clear. “The way I write, since I do leave out most of the connections, and very little is pinned down, I feel that I’m doing a minimum of damage to other possibilities that might arise in a reader’s mind,” he told Schiff. He disliked, he said, writers who “forced a personality” on him, or who were “completely exhaustive about whatever it is they’re writing about until you’re just left feeling ‘O.K., you’ve nailed me to the chair, that’s it, there’s nothing left to think about, there’s nothing left to question.'” (Not afraid to name names, he told Schiff that his least favorite writers were Thomas Mann and Henry James—”I hate Henry James more than tongue can tell,” he said. “I have read everything he wrote, sometimes more than once. I think he’s the worst writer in the English language.”)

“My favorite genre is the sinister-slash-cozy,” Gorey added.

I think there should be a little bit of uneasiness in everything, because I do think we’re all really in a sense living on the edge. So much of life is inexplicable. Inexplicable things happen to me; things that are so inexplicable that I’m not even sure that something happened. And you suddenly think, ‘Well, if that could happen, anything could happen.’ One moment, something is there, and then, the next, it is not there. One minute, both of my feet are perfectly all right, and then, a minute later, somebody has dropped a fifty-pound weight on one of them, and now suddenly I’ve got an injured foot and I have to go do something about this injured-foot thing. The things that happen to you are usually the things that you haven’t thought of or that come absolutely out of nowhere. And all you can do is cope with them when they turn up.

The something, the something else, the unexpected, the world-changing, and all of us on the edge, all of us left grasping. That sounds like good art, all right.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.