Edward Gorey, like all incoming freshmen, had been assigned to one of the residence halls around Harvard Yard. Mower, a small red-brick building completed in 1925, has its own courtyard, a patch of tree-shaded green that gives it a secluded feel. Gorey’s new home was suite B-12, on the ground floor, a no-frills affair with two bedrooms giving onto a common study room with three desks and a fireplace. His roommates were Alan Lindsay and Bruce Martin McIntyre, about whom we know zilch, as he would say.

In his first month at Harvard, Gorey met a fellow veteran and fledgling poet with whom he soon formed a two-man counterculture. Frank O’Hara, his upstairs neighbor in Mower B-21, would go on to fame as a leading light in the New York School of poets (which included John Ashbery and Kenneth Koch, both Harvardians as well). Brilliant, intellectually combative, lightning quick with a witty comeback, O’Hara was a virtuoso conversationalist who turned cocktail-party repartee into an improvisatory art.

Like Gorey, he’d come to Harvard on the GI Bill. He, too, was Irish Catholic, but whereas Ted had slipped the traces of a Catholic upbringing early on, O’Hara had all the post-traumatic baggage of the lapsed Catholic: “It’s well known that God and I don’t get along together,” he wisecracked in one of his poems. But the most obvious evidence that he and Gorey were cast in the same mold was O’Hara’s “drive for knowing about all the arts,” an impulse that “was as tireless as it was unfocused,” according to his biographer Brad Gooch, who adds that “he showed a genius, early on, for being in the know”—another Goreyan quality. By 1944, when he enlisted in the navy, he’d become “something of an expert on the latest developments in 20th-century avant-garde music, art, and literature,” mostly by way of his own autodidactic curriculum, Gooch writes. Like Gorey, O’Hara was fluent in modern art, bristling with opinions on Picasso, Klee, Calder, and Kandinsky. At the same time, he shared Ted’s passion for pop culture, which for O’Hara meant the comic strip Blondie, hit songs by Sinatra and the big-band trumpeter Harry James, and, most of all, film: he was an ardent moviegoer, papering his bedroom walls with pictures of popcorn Venuses like Marlene Dietrich and Rita Hayworth. Insatiable in his cultural cravings, all-embracing in his tastes, unreserved in his opinions, O’Hara was in many ways Gorey’s intellectual double, down to the fanatical balletomania.

The two were soon inseparable. They made a Mutt-and-Jeff pair on campus, O’Hara with his domed forehead and bent, aquiline nose, broken by a childhood bully, walking on his toes and stretching his neck to add an inch or two to his five-foot-seven height, Gorey towering over him at six two, “tall and spooky looking,” in the words of a schoolmate.

Swanning around campus in his signature getup of sneakers and a long canvas coat with a sheepskin collar, fingers heavy with rings, Gorey was the odds-on favorite for campus bohemian, with the emphasis on odd. “I remember the first day Ted Gorey came into the dining hall I thought he was the oddest person I’d ever seen,” said George Montgomery. “He seemed very, very tall, with his hair plastered down across the front like bangs, like a Roman emperor. He was wearing rings on his fingers.” Larry Osgood, a year behind Ted, shared Montgomery’s double-take reaction the first time he saw Gorey. He was standing in line to buy a ticket to a performance by the Martha Graham Company when he noticed a “tall, willowy man” with his nose in a little book. “Ted never stood in line for anything without a book in his hands,” says Osgood. “One of the things that struck me about him and made me, in my philistine way, sort of giggle at him was [that] one of his little fingernails was about three inches long. He’d let it grow and grow and grow.”

Swanning around campus in his signature getup of sneakers and a long canvas coat with a sheepskin collar, fingers heavy with rings, Gorey was the odds-on favorite for campus bohemian, with the emphasis on odd.

Gorey struck an effete pose. He affected a world-weariness and tossed off deadpan pronouncements with a knowing tone, an irony he underscored with broad, be-still-my-heart gestures—“all the flapping around he did,” a fellow dorm resident called it. Even so, he wasn’t some shrieking caricature of pre-Stonewall queerness. “He was flamboyant in a much more witty and bizarre way that normal queens weren’t,” says Osgood. “Giving big parties and carrying on, listening to records of musicals and singing along to them” wasn’t Gorey’s style.

As always, Gorey defied binaries. His eccentric appearance belied a shy, reserved nature. His speech, body language, and cultural passions—theater, ballet, the novels of gay satirists of mores and manners such as Saki, Ronald Firbank, E. F. Benson, and Ivy Compton-Burnett—were a catalog of stereotypically gay traits and affinities. Yet no one in the almost exclusively gay crowd he traveled with ever saw him at gay bars such as the Napoleon Club or the Silver Dollar. He was either so discreet that he eluded detection or, as he later maintained, so yawningly uninterested in sex that there was nothing to detect.

O’Hara was impressed by Gorey’s assured sense of himself, his refusal to apologize for his deviations from the norm, especially his blithe disregard for conventional notions of masculinity. O’Hara, who’d had his first same-sex experience when he was 16, was conflicted about his sexual identity—all too aware of his attraction to men but gnawed by the suspicion that gay men were sissies and haunted by fears of what would happen if his secret got out in the conservative Irish Catholic community where he’d grown up, in Grafton, Massachusetts. Posthumously, O’Hara would take his place on the Mount Rushmore of gay letters, but during his Harvard years he was torn between the closeted life he was forced to live whenever he returned home and the more liberated life he lived at Harvard and in Boston’s gay underground.

Gorey’s comparatively over-the-top persona was a revelation to O’Hara. “As his life in [his hometown] became more weighted and conflicted, O’Hara compensated by growing increasingly flamboyant at Harvard,” writes Gooch. “His main accomplice in this flowering was Edward St. John Gorey,” who constituted O’Hara’s “first serious brush with a high style and an offbeat elegance to which he quickly succumbed.”

Style is key here: consciously or not, Gorey was acting out a “revolt through style,” a phrase coined by cultural critics to describe the symbolic rebellion, staged in music, slang, and fashion, by postwar subcultures—mods, punks, goths, and all the rest of them. Gorey wasn’t so much rebelling against the conformist, compulsorily straight America of the late 40s as he was airily disregarding it, decamping to a place more congenial to his sensibility, a world concocted from his far-flung fascinations and conjured up in India ink.

Growing up, Gorey and O’Hara had always been the smartest kids in any room they walked into. Now each had met his match, not just in IQ points but in cultural omnivorousness, creativity, and oblique wit. They fed off each other’s enthusiasms, seeing foreign films at the Kenmore, near Boston University; sneaking into the ballet during intermission at the old Boston Opera House, on Huntington Avenue; and attending poetry readings on campus given by Wallace Stevens, W. H. Auden, Edith Sitwell, and Dylan Thomas. Poking around in bookstores near Harvard Square, they initiated one another into the esoteric charms of writers sunk in obscurity.

O’Hara was impressed by Gorey’s assured sense of himself, his refusal to apologize for his deviations from the norm, especially his blithe disregard for conventional notions of masculinity.Ronald Firbank (1886-1926), a little-known English novelist of the 20s, was typical of their rarefied tastes. If Gorey and O’Hara’s aesthetic cult had a patron saint, it was Firbank, whose influence on both men lasted long after Harvard. O’Hara’s wordplay, his ironic humor, and his witty interpolation, in his poems, of snippets of overheard dialogue owe much to Firbank. As for Gorey, he once cited the author as “the greatest influence on me . . . because he is so concise and so madly oblique,” though he later qualified his admiration, conceding that he was “reluctant to admit” his debt to Firbank “because I’ve outgrown him in one way, though in another I don’t suppose I ever will. Firbank’s subject matter isn’t very congenial to me—the ecclesiastical frou-frou, the adolescent sexual innuendo. But the way he wrote things, the very elliptical structure, influenced me a great deal.” (Gorey repaid the debt in 1971 when he illustrated a limited edition of Two Early Stories by Firbank.)

He also took from Firbank what he took from Japanese and Chinese literature, namely, the aesthetic of “leaving things out, being very brief,” to achieve an almost haikulike narrative compression. (“I think nothing,” Firbank declared, “of filing fifty pages down to make a brief, crisp paragraph, or even a row of dots.”)

Gorey admired Firbank’s exquisitely light touch, his mastery of an irony so subtle it was barely there; we hear echoes of Firbank’s drily hilarious style in Gorey’s prose and in his conversational bon mots. To the Goreyphile, Firbank sounds startlingly Goreyesque: “The world is disgracefully managed, one hardly knows to whom to complain.” In Vainglory (1915), Lady Georgia Blueharnis thinks the view of the hills near her estate would be improved “if some sorrowful creature could be induced to take to them. I often long for a bent, slim figure to trail slowly along the ridge, at sundown, in an agony of regret.” Can’t you just see that bent, slim figure trailing slowly through the twilight of a Gorey drawing?

A writer’s style is inextricable from his way of looking at the world, and Gorey absorbed Firbank’s sensibility along with his style. His habit of treating serious subjects frivolously and frivolous matters seriously, his love of the inconsequential and the nonchalant, his carefully cultivated ennui, his puckish perspective on the human comedy: all these Goreyesque traits bear the stamp of Firbank’s influence.

Even Gorey’s stifled-yawn lack of interest in the subject of sex—“Such excess of passion / Is quite out of fashion,” a young lady observes in The Listing Attic—has its parallel in the can’t-be-bothered languor that was part of the Firbank pose. “My husband had no amorous energy whatsoever,” one of his characters confides, “which just suited me, of course.”

Gorey’s most obviously Firbankian attribute is his immersion in the nineteenth century. Firbank was besotted by the same fin-de-siècle literature and aesthetic posturing whose influence wafts off the pages of Gorey’s Dugway plays. A throwback to the Mauve Decade, he was “1890 in 1922,” to quote the critic Carl Van Vechten. (“I adore all that mauvishness about him!” a Firbank character cries.) Yet, like Gorey, he was very much of his moment: his compressed plots and collagelike rendering of cocktail-party chatter were as modern in their own way as Gorey’s Balanchinian economy of line, absurdist plots, and pared-down texts were in theirs.

Firbank, it should go without saying, was gay. He looms large in the prehistory of camp, the coded sensibility that enabled gays, in pre-Stonewall times, to signal their sexuality under the radar of mainstream (read: straight) culture and, simultaneously, to mock that culture with tongue firmly in cheek. To gay readers who could read the subtext in Firbank’s pricking wit and “orchidaceous” style, as detractors called it, his prose hid his queerness in plain sight.

“As his life in [his hometown] became more weighted and conflicted, O’Hara compensated by growing increasingly flamboyant at Harvard.”

The content of his novels, which poked fun at bourgeois institutions such as marriage, had special meaning for gay readers, too. “One can imagine how such a flagrant parody of heterosexual mores might function within the gay subculture—reinforcing the self-esteem of those who thought their nontraditional sexuality a rebellion against the conventionalism of late Victorianism,” writes David Van Leer in The Queening of America. “An appreciation of [Firbank] became the litmus test of one’s sexuality and of one’s allegiance to the dandyism of post-Wildean homosexuality. When gay poet W. H. Auden announced that ‘a person who dislikes Ronald Firbank may, for all I know, possess some admirable quality, but I do not wish ever to see him again,’ his statement was not an aesthetic judgment. It was a declaration of community solidarity.”

It’s hard to imagine Gorey rejoicing in the gay “community solidarity” signaled by a fondness for Firbank. A nonjoiner if ever there was one, Gorey distanced himself from those, like the “very militant” museum curator he knew in later years, who insisted that their queerness was central to their identity. “I realize that homosexuality is a serious problem for anyone who is—but then, of course, heterosexuality is a serious problem for anyone who is, too,” he said. “And being a man is a serious problem and being a woman is, too. Lots of things are problems.”

Too true. But being a homosexual in 1946, or facing up to the fact that you might be, was surely just a little bit more serious, as problems go, than being heterosexual. When Gorey arrived on campus, the Harvard Advocate was defunct, closed in the early 40s by outraged trustees who’d discovered that its editorial board was, for all purposes, a gays only club. When the magazine resumed publication in 1947, it did so with the understanding that gays were banned from the board (a prohibition everyone disregarded but that was nervous-making nonetheless). During Gorey’s Harvard days, a student caught making out with another young man was expelled. Shortly after he graduated, in the spring of 1951, two Harvard men who’d engaged in what O’Hara’s biographer calls “illicit activities” got the axe as well—a regrettable affair that turned into a “horrible tragedy,” says Gorey’s schoolmate Freddy English, when one of the young men committed suicide.

Whether Gorey thought of himself as gay at Harvard and whether his emerging style and sensibility represented a coming to terms with his sexuality he never said. Still, as noted earlier, nearly all his influences during those formative four years, from Firbank to Compton-Burnett to E. F. Benson, were gay. Then, too, the fact that he was surrounded, for the first time in his life, by unmistakably gay men—one of whom, Frank O’Hara, had become a close friend (though not, it should be emphasized, a lover)—must have pressed the question of his own sexuality.

When Gorey arrived on campus, the Harvard Advocate was defunct, closed in the early 40s by outraged trustees who’d discovered that its editorial board was, for all purposes, a gays only club.If he, like O’Hara and others in their clique, was struggling with his identity, the pervasive homophobia of the times must have affected him in some way. With the coming of the Cold War, right-wing opportunists whipped up fears of communist infiltration at the highest levels of government. Gays, they maintained, were an especially worrisome threat to national security, since their “perversion” rendered them vulnerable to being blackmailed into spying for the Russkies. Harvard’s expulsions of gay students made the mood of the moment impossible to ignore.

A report by Gorey’s freshman adviser, Alfred Hower, hints at shadows moving beneath the witty insouciance he showed the world. “Gorey seems a rather nervous type and not particularly well adjusted,” Hower writes, adding, hilariously, “He started to grow a beard, which may or may not be an indication of some eccentricity.”

When his frequent absences from Harvard’s required “physical training” course landed him on academic probation, his mother pled his case with Judson Shaplin, the assistant dean of the college. In a revealing letter, she laments the difficulty Ted is having adjusting to the demands of college life, noting that he coasted through grade school and as a result “just never learned how to study,” a weakness compounded, in her eyes, by Parker’s unorthodox, no-grades approach to academics. But the roots of her son’s fecklessness lie, she suggests, in the fact that Ted, “as the only child of divorced parents . . . has been handicapped by a combination of too much mother and too little masculine influence.”

To our ears, Helen Gorey’s pat analysis of her son as a mama’s boy, infantilized (and, presumably, sissified) by a smothering mother, sounds like an outtake from the script for Hitchcock’s Psycho. But she was only echoing the Freudian wisdom of her day. “From the 1940s until the early 1970s, sociologists and psychiatrists advanced the idea that an overaffectionate or too-distant mother . . . hampers the social and psychosexual development of her son,” Roel van den Oever asserts in Mama’s Boy: Momism and Homophobia in Postwar American Culture.

It seems likely that this mounting intolerance toward gays—or, for that matter, any weirdo who came off as “very, very faggoty” (George Montgomery’s first impression of Gorey)—would have unsettled a college student trying to make sense of who he was. A nightmarish little vignette in Gorey’s collection of limericks, The Listing Attic (most of which he wrote “all at once” in ’48 or ’49), suggests something was troubling him.

At night, in a scene straight out of Hawthorne or Poe but perfect for the lynch-mob mentality of the McCarthy era, capering men encircle a statue, brandishing torches. On top of the statue—the famous bronze likeness of John Harvard in Harvard Yard—a terrified figure cowers as one of the revelers strains with outstretched torch to set him on fire. In the foreground, black trees shrink back in horror; even their shadows recoil, stretching toward us in the firelight. Gorey writes,

Some Harvard men, stalwart and hairy, Drank up several bottles of sherry;

In the Yard around three

They were shrieking with glee:

“Come on out, we are burning a fairy!”

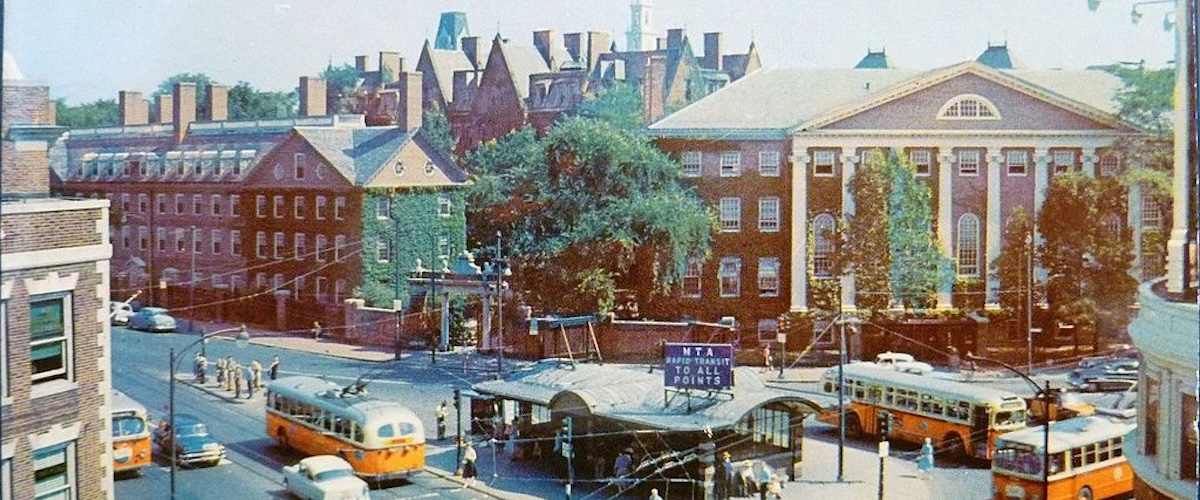

Within a month of meeting, Gorey and O’Hara had decided to room together. On a November 21, 1946, application for a change of residence, Gorey says he’d like to move to Eliot House, a residential house for upperclassmen whose invigorating mixture of aesthetes, athletes, scholars, and “Eliot gentlemen” (young men with Brahmin surnames like Cabot and Lodge) was handpicked by the housemaster and eminent classicist John Finley. A devout believer in Harvard’s house system, which was modeled on Oxford’s residential colleges, Finley fostered the life of the mind over tea parties and at more formal symposia featuring luminaries such as the poet Archibald MacLeish and I. A. Richards, a founding father of New Criticism.

It wasn’t until the beginning of Gorey’s sophomore year, in the fall of ’47, that Harvard approved his move to Eliot, where he and O’Hara ended up in suite F-13, a triple. O’Hara took one of the two little bedrooms; the third man, Vito Sinisi—a philosophy major who, in a zillion-to-one coincidence, had studied Japanese with Gorey in the Army Specialized Training Program at the University of Chicago—called dibs on the other; and Gorey slept in the suite’s common room. By day, he could often be found there, at a big table near a window, drawing his little men in raccoon coats.

Gorey and O’Hara transformed their suite into a salon, furnishing it, in suitably bohemian fashion, with white modernist garden furniture rented from one of the shops in Harvard Square. A tombstone, pilfered from Cambridge’s Old Burying Ground or perhaps from Mount Auburn Cemetery and repurposed as a coffee table, added just the right touch of macabre whimsy. (Founded in 1831, Mount Auburn is a bucolic necropolis in Cambridge, not far from Harvard. It’s inconceivable that Gorey didn’t frequent its winding paths; judging by his books, the prop room of his imagination was well stocked with Auburn’s gothic tombs, Egyptian revival obelisks, and sepulchres adorned with urns and angels.)

Gorey and O’Hara decorated F-13 with soirees in mind; it was just the sort of place for standing contrapposto, cocktail in one hand, cigarette in the other, making witty chitchat. “The idea,” said O’Hara’s friend Genevieve Kennedy, “was to lie down on a chaise longue, get mellow with a few drinks, and listen to Marlene Dietrich records. They loved her whisky voice.” (Dietrich was to gay culture in the ’40s what Judy Garland would be to later generations of gay men. Gorey carried a torch for her long after Harvard.)

Gorey and O’Hara continued to swap newly discovered enthusiasms and kindle each other’s obsessions. The 50s would witness the birth pangs of what the 60s would call the counterculture. As youth culture pushed back against the father-knows-best authoritarianism and mind cramping conformity of postwar America, Hollywood and the news media provided teenagers with templates for rebellion: the brooding, alienated rebel without a cause role-modeled by James Dean; the beatniks in Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” (1956) and Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957). At Harvard in 1947, though, countercultures were strictly do- it-yourself affairs. Gorey and O’Hara were a subculture unto themselves within a larger subculture, the gay underground. At a moment when T.S. Eliot’s high-modernist formalism held sway in literature classes and little magazines, its brow-knitting seriousness and self-conscious symbolism the order of the day, Gorey and O’Hara embraced the satirical, knowingly frivolous novels of writers like Firbank, Compton-Burnett, and Evelyn Waugh.

Gorey and O’Hara were a subculture unto themselves within a larger subculture, the gay underground.Gorey and O’Hara and their clique weren’t defiantly nonconformist (although they were obliquely so) or overtly political (though there was a politics to their pose). Nor were they populist in the Whitmanesque way the Beats were or in the communitarian way the hippies were. Even so, says Gooch, “they were a counterculture,” albeit “an early and élitist form of it”—textbook examples of what the cultural critic Susan Sontag called the “improvised self-elected class, mainly homosexuals, who constitute themselves aristocrats of taste.”

Joined, over time, by kindred spirit John Ashbery—a class ahead of them at Harvard and destined to win acclaim as a major voice in American poetry—Gorey and O’Hara defined themselves through their tastes, sense of style, and aesthetic way of looking at the world.

“Nobody was organized; there was just style, so to speak, rather than movements,” says the critic and novelist Alison Lurie, a close friend of Gorey’s at Harvard and afterward, during his Cambridge period. To Lurie, Gorey and his friends “represented an alternative reality” to the blustering machismo of iconic he-men like Norman Mailer (who impressed her as “a noisy, bullying kind of person” when she met him through his sister, Barbara, her classmate at Radcliffe).

Gorey, O’Hara, and their circle recoiled from the strutting, pugnacious masculinity epitomized by Mailer, but they staked out their position through taste, not the sort of polemical tantrums he staged. Ted “loved Victorian novels and Edwardian novels,” Lurie recalls. “He would never have read with much pleasure The Naked and the Dead. This macho thing was very irritating to Ted and his friends. . . . So if you were tired of men behaving this way, these writers were very encouraging to you.” Vets who’d seen combat, as Mailer had, looked down on men who hadn’t, like Gorey, Lurie notes, “and sometimes they would show this, you know? So I suppose there was this kind of reaction to this violent masculine mystique that some of these guys came back with.”

Gorey, O’Hara, and their inner circle shared an affection for the self-consciously artificial, the over-the-top, and the recherché. Their ironic, outsider’s-eye view of society often expressed itself in the parodic, highly stylized language of camp. In her essay “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” Sontag defines that elusive sensibility as a “way of seeing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon . . . not in terms of beauty but in terms of the degree of artifice, of stylization”—a definition that harmonizes with Gorey’s remark, “My life has been concerned completely with aesthetics. My responses to things are almost completely aesthetic.”

___________________________________

Excerpted from Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey. Copyright © 2018 by Mark Dery

Used with permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York. All rights reserved.