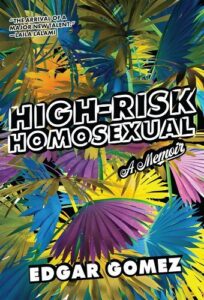

Edgar Gomez on Sex, Desire, and Going on PrEP

Also, Being Dubbed a "High-Risk Homosexual"

A few weeks before I started taking PrEP, the once-a-day pill that would reduce my risk of contracting HIV by nearly 100 percent, a man traveling on business messaged me on Grindr, inviting me to his hotel room. I’ve always been jealous of my gay friends who hook up with abandon. The ones who visit bathhouses as casually as if they were going candle shopping at Target. The apps allow me to pretend I’m like them. Chill about sex. Reading the man’s message, I tried to picture myself showing up to his room. The door would be unlocked, he told me. He’d be waiting inside, facedown, ass up on the mattress. I could do whatever I wanted. I began to type out a response, but then the same anxiety crept in that always did, instantly shattering my desire.

What if I brushed my teeth too hard, and in one of the back rows there was a little cut, small enough not to notice but big enough for HIV to wiggle its way in?

My nails. I bite them till they bleed. All those wounds. What if his semen touches my fingers and . . . ?

And if the condom slips off? Or breaks?

And if he bites my lip?

And if he doesn’t regularly get tested?

I logged out. It was too . . . stressful. Too . . . scary. The rare times I did have casual sex, I had to bury my face in a pillow to stifle my nervous laughter while thinking, Hope he’s worth it, because this might kill you!

It wasn’t funny, but it felt true.

Perhaps educating myself would have relieved my overblown fear, but the little I did know about HIV terrified me enough, and I was afraid of what else I might discover if I looked closer. I knew the stigma surrounding HIV was so pervasive that even for people who are positive and undetectable (meaning the amount of virus in their blood is so low it is impossible to transmit through sex), dating became more difficult than it already was. The language men use on the apps alone was proof of that: “Clean and looking for same,” some write, like having an STD makes you dirty.

I knew that in high school, a new friend had been so cautious of sharing his status with me that while getting to know each other, he constantly accused strangers of having AIDS, probably to gauge my reaction before deciding whether I was trustworthy. I knew there was medicine, he must have been on it, but that it was costly, and in a year the insurance I had through my graduate school program would end. Add to all that what I knew from television and films.

If my life was to be anything like those of the queer people on Lifetime, after coming out of the closet as a teenager, I was destined to spend the next few years dodging mobs of gay bashers. College would be a montage of close-ups of me inhaling poppers under a disco light, pairs of underwear strewn on my bedroom floor next to empty bottles of vodka. These would be the “fun” years, artfully selected to seduce viewers into thinking the gay lifestyle was worth it. But then, some distant morning at the wise gay age of 27, I would wake up with a sharp pain in my thigh, trace it with my fingertips to a purple lesion.

A few months later a nurse would be spoon-feeding me applesauce at a hospice. Flash forward to my funeral, my mother draped over my casket, one or two friends in the back of the church. The ending credits would roll over the image of them weeping, the survivors, left behind to warn the next generation.

That last part, at least, isn’t fiction, because the gay people who lived through the early days of the crisis did warn me. In the art I grew up with. In the cautionary tales many of them told. Be careful, they said. Sex can kill you. Look what it did to us. I don’t doubt their words came from a place of love and immeasurable hurt. They couldn’t have known the side effects of hearing that message over and over, that screenwriters would take it and multiply it by a thousand so straight people would have something morbid and exotic to consume for their entertainment, that I would turn to those movies seeking reflection and find in them only loss. They just wanted me to have a chance. Now there was a new voice saying: With PrEP, you do. Write something new.

The day I received my first bottle of little blue pills was a blur. I’d been so thrilled to qualify for the drug that I didn’t look closely at the prescription I was handed by Dr. Chen, my doctor at my university’s health center. She told me it would take two weeks for the antiviral in PrEP to reach a high enough level in my body to fight HIV, another two before the side effects like nausea and nightmares would go away. As she spoke, a clock started counting down in my mind. One month, then I could go out and have fearless sex. That’s all I could focus on.

On my fourth week, after passing a series of lab tests, Dr. Chen gave me the prescription for my second bottle. This time, I did look at it.

I looked at it, bewildered, for a long, long time.

There was my name: Edgar Gomez. My age: Twenty-five years old. And some words that I guessed referred to me, though I didn’t know how they applied: High-Risk Homosexual.

At home, I read-read the prescription, not sure how to feel. “High-Risk.” Was I that? What did those words even mean? They sounded like something you might see flashing on screen in an animal cruelty commercial. For the price of your daily cup of coffee, you could save this high-risk homosexual. I couldn’t help but think of all the times people had taken pity on me for being queer, for being poor, for being the child of a Central-American immigrant single mother who supported our family by working as a cashier at Starbucks, as if there was no way I could be those things and happy. As if we surely spent every night sobbing and rocking ourselves to sleep, clutching our empty bellies. I didn’t need their pity, and I didn’t want them to give up their coffee. If they did that, mom would lose her job. Then I’d really be a high-risk homosexual.

I shoved the prescription into a drawer, logged on to Grindr, fell into bed, and covered my head with a pillow. I had enough things on my mind without having to wonder why I’d been suddenly reduced to those three words. Things like sex, which was the reason I got on PrEP in the first place. I mean, to go from “If you sleep with someone, you’ll die” to “Just kidding! Be a ho!” was such an earth-shattering shift that I still couldn’t believe one pill a day was all it took. Lying there, my phone vibrated with a new message. I poked my head out from beneath my pillow.

His name was Carlos, and he was only free for a few hours. Did I want to join him in his car for some fun?

Within forty-five minutes, I was in the passenger seat of a Mustang, admiring the spaceship features on his dashboard and trying to act casual. This wasn’t supposed to be revolutionary. We weren’t supposed to be battling stereotypes. He and I were just two people, about to fuck.

“You’re on PrEP, right?” he asked almost immediately.

“Uh-huh,” I said, though I’d already told him so in our messages.

A small monitor below his radio fed footage from a hidden camera in the rear of his car. Behind us, there was nothing but gravel. We were parked in a spot tucked behind my apartment. I didn’t want him coming inside. I didn’t want my straight roommates thinking I was the kind of guy who met randos online and brought them home. A high-risk homosexual, or whatever.

“Cool. Wanna move to the back?” He unbuckled his seatbelt. “There’s more room.”

I kept my eyes on the gravel. “Don’t you want to turn your car off?” I asked.

He crawled over the divider, briefly looking over his shoulder to say, “Nah. This shouldn’t take that long.”

It didn’t.

Half an hour later I was back in bed with my palm resting on my stomach, feeling Carlos swimming inside of me. I couldn’t remember ever being so aware of my body. Then again, I rarely swallowed. I hated the taste of semen, how you couldn’t ever predict the flavor, the way some men squeezed out every drop and presented it to me as if it were artisanal toothpaste.

Somewhere in my belly, something growled. The air conditioner rattled away on its coolest setting. A trickle of sweat fell from my forehead, snaking its way down my neck. Is it working? Is it working? Is it working? I wondered, thinking about the so-called miracle drug that was meant to take this anxiety away.

What if you didn’t take enough?

Or you needed to wait a little longer for it to become effective?

What if you’re one of the 0.01 percent it doesn’t work on?

What if you’re exactly who everyone thinks you are? What does that make you then?

__________________________________

From High-Risk Homosexual: A Memoir by Edgar Gomez, available via Soft Skull Press.