Ebony Thomas on Seeking the Fantastic When the World Tells You Not To

Writing Towards Magic as a Person of Color

“There is no magic.”

This statement, perhaps most famously attributed to Harry Potter’s uncle Vernon Dursley, is also something that my mother has said to me since I was a child. Magic has long been under siege in my culture, social class, and hometown. The eldest daughter of an African American, working-class, Detroit family, I was born in the late 1970s just as the fires of the Civil Rights era were smoldering to ashes.

My mother was doing me a favor by letting me know that magic was inaccessible to me. The real world held trouble enough for young Black girls, so there was no need for me to go off on a quest to seek it. I was warned against walking through metaphoric looking glasses, trained to be suspicious of magic rings, and assured that no gallant princes were ever coming to my rescue. The existential concerns of our family, neighbors, and city left little room for Neverlands, Middle-Earths, or Fantasias. In order to survive, I had to face reality.

My life has been intentionally constructed to prove my mother’s words wrong. Among my earliest memories are snapshots taken from behind the spectacles of my younger self, seeking desperately for any traces of magic in the real world, even when magic did not seem to search for—or take much notice of—me.m

[The] problem of representation has created discord in the collective imagination.

Secret passageways remained closed off to me, but I continued to dream. Books were my ticket to the realm of the imagination; reading, a welcomed escape. Although I grew up in urban America during the height of the crack epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s, my heart, mind, and soul were almost always somewhere else. In the realm of the fantastic, I found meaning, safety, catharsis—and hope. Though it eluded me, I needed magic.

*

My emerging critical consciousness as a reader, creative writer, and fangirl were soon on a collision course with my experiences as a teacher, scholar, and critic. The promise from Disney’s classic Cinderella film, “In dreams you will lose your heartache… whatever you wish for, you keep,” was obscured by the real conditions of my existence as a young Black woman in early twenty-first century America. It was also obscured in the lives of my family and friends, and in the lives of many children and adults whom I knew. Perhaps this is why some of my students, family members, and friends have been especially ambivalent about speculative fiction. They prefer to read and view stories that are, in their words, “true to life” or “keeping it real.” Although there are many exceptions to this conventional wisdom about Black readers’ and viewers’ genre preferences—the recent Black Panther phenomenon for one—I have been told throughout my lifetime that stories like the ones I preferred were “for White people.”

When people of color seek passageways into the fantastic, we have often discovered that the doors are barred. Even the very act of dreaming of worlds-that-never-were can be challenging when the known world does not provide many liberating spaces.

A poignant example comes from Marlon Riggs’s Emmy-award winning 1986 documentary about racial representation in media, Ethnic Notions. Toward the end of the film, there is a haunting sequence in which Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech is interposed over Ethel Waters’s ethereal performance of “Darkies Never Dream” in the 1943 movie Cabin in the Sky. While others have read her performance through the lens of minstrelsy, for me, it was almost as if Ethel’s haunting melody was audaciously pointing to the possibility of the endarkened future of King’s March on Washington, and beyond it to our time—a time when all people would ostensibly have access to the pleasures of dreaming.

But are the cartographies of dreams truly universal? When we dream inside the storied worlds of printed and digital books, fanfiction, fan-art, fan videos, television shows, movies, comics, graphic novels, online fandom communities, and fan “cons,” do those worlds offer all kinds of people escape from the world as we know it? Could they offer catharsis for some of our most pressing human problems? Might they help us collectively imagine our world anew?

This conversation is even more critical in today’s social media environment, described by media theorist Henry Jenkins as convergence culture, in which traditional and new media forms thrive together. Since today’s young people are as likely to be engaged in virtual social worlds as they are in face-to-face communication, the ways that stories are told and retold in convergence culture are more significant than ever for shaping the collective consciousness. As Jenkins notes:

Transmedia storytelling is the art of world making. To fully experience any fictional world, consumers must assume the role of hunters and gatherers, chasing down bits of the story across media channels, comparing notes with each other via online discussion groups, and collaborating to ensure that everyone who invests time and effort will come away with a richer entertainment experience.

Today’s teens and young adults are increasingly using new forms of communication to read and tell stories. They engage in textual and visual production that is collaborative, shared in what has been characterized as environments of digital intimacy. Digitally intimate virtual communities have their own ever-evolving rules, norms, and assumptions about meaning-making processes, authorship, and composing. As people participate with one another across these affinity spaces and networked publics, they engage in participatory cultures in which “everyday citizens have an expanded capacity to communicate and circulate their ideas . . . [and] networked communities can shape our collective agendas.”

Though it eluded me, I needed magic.

This participatory turn has made it possible for more people to produce individual and collaborative content as part of their everyday lives, using a wide variety of multimodal tools to make meanings that are increasingly decentralized, crowdsourced, and situated in a multiplicity of contexts. A wide variety of communicative channels, modalities, and meanings helps to expand the stories that get told, circulated, and remixed, thereby challenging single stories about individuals and groups, and opening up interpretive space for multiple possible meanings.

While digitally networked culture affords more scope for the imaginations of young people, this is not universally the case. Although a sense of the infinite possibilities inherent in fantasy, science fiction, comics, and other imaginative genres draws children, teens, and adults from all backgrounds to speculative fiction, not all people are equally represented in these genres. This problem of representation has created discord in the collective imagination. The dark fantastic is my attempt to understand that discord as it plays out in stories for young adults and in audience interactions with those stories.”

![]()

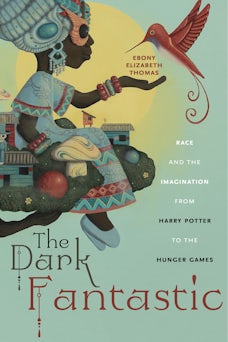

From Ebony Elizabeth Thomas’s The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination From Harry Potter to the Hunger Games. Excerpted with permission of the publisher, New York University Press. Copyright 2019 by Ebony Elizabeth Thomas.

Ebony Elizabeth Thomas

Ebony Elizabeth Thomas is Associate Professor in the Literacy, Culture, and International Educational Division at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education. A former Detroit Public Schools teacher and National Academy of Education/Spencer Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow, she is an expert on diversity in children’s literature, youth media, and fan studies. The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to the Hunger Games is out May 2019 from NYU Press.