We Have This Device. It’s Called a Book.

How science fiction sees the future of reading

Speaking to the American Booksellers Association in 1989, science fiction demi-god Isaac Asimov asked his audience to imagine a sci-fi information storage device that, “Can go anywhere, and is totally portable. Something that can be started and stopped at will along its data stream, allowing the user to access the information in an effective, easy manner.” After what I imagine was a dramatic pause, Asimov answered his own sci-fi riddle: “We have this device. It’s called a book.”

Twenty-five years later, given our actual onscreen-reading habits, the answer to Asimov’s riddle is less obvious. In 2015, is the traditional book format still our most elegant reading technology? Maria Konnikova, speaking to the Slate podcast, the Gist, last year, thinks the answer is “maybe.”

“We do know that certain ways of presenting text are easier than others. And the traditional book format, believe it or not, has been shown to be one of the best ways for our eyes to read.”

Konnikova takes great pains to point out that she doesn’t necessarily think reading from a screen is worse than reading from a page, and is careful to push the notion of direct light versus reflected light out of the debate. Instead, she posits there’s “…something about the tangibility of pages…and what we know about information and the way we process information is that we think spatially.” She then elaborates on the idea that reading comprehension might be better, or at least, preserved better in our brains from the experience of a physical book versus a screen.

Asimov’s slick little riddle, aside from providing reassurance to his audience, was also a response to a decade of technological breakthrough, as the personal computer of sci-fi’s collective imagination became a reality. Science fiction had imagined it, and so it came to pass. So, what else does our literature of the future tell of us of the book? Does it survive? Will it remain the “most effective, easy storage device”?

Inarguably the best of the Star Trek films, 1982’s Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, is also the most literary. In an early scene, Spock gives Captain Kirk a hardbound copy of A Tale of Two Cities, because he knows of Kirk’s “fondness for antiques”: in Star Trek’s 23rd-century future, real books are curiosities of the distant past. This kind of winking hyperbole is everywhere in pop sci-fi, where the medium isn’t just the message, but also the gag. Back in 1984, the brainiest member of the Ghostbusters—Egon Spengler (the late Harold Ramis)—anticipating a millennial deluge of thousand-word think pieces, online and otherwise, told us “print is dead.” So, is it?

From the book bonfires of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 to the conspicuous absence of literature in Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games, the future of the book—in literature, cinema and television alike—is not a happy one. In a vast majority of futuristic science fiction, reading books—or at least the owning of books—is no longer a part of everyday life. (This isn’t to say these are all bookless dystopias: the plot of sci-fi, b-movie “classic,” Zardoz, for example, hinges on Sean Connery’s discovery of Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz in an abandoned library. Sadly, Connery’s character fails to find any books on fashion, which might explain the bright red adult diapers and thigh-high boots.)

The uber-geek-chic sci-fi adventure show, Doctor Who often tries to correct for the bleak inevitability of a bookless future, and in a memorable 2008 two-part storyline—“Silence in the Library”— the Doctor himself declares “Books! People never really get tired of books!” The episode takes place on a planet called “The Library,” which has continents divided into genres (the equator is biographies!) and a planetary core that is a giant card-catalogue hard drive. But the books in “The Library” are not originals. Instead, the automated world produces all new editions of any kind of book imaginable. At first glance, a Library Planet seems like it would be a book-lovers’ dream… but then the ugly question surfaces: where, in this print-on-demand paradise, have all the original print books gone? The answer is pretty obvious.

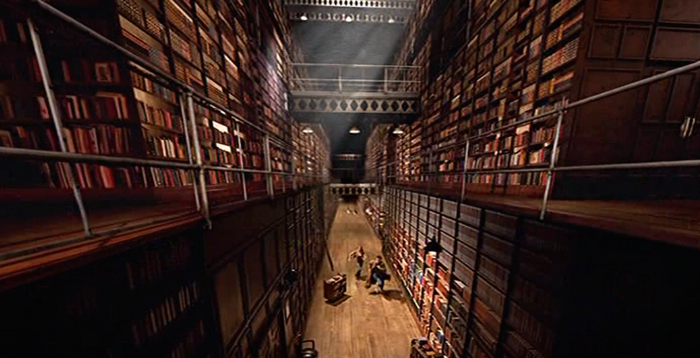

Quiet, please. You’re inside the Library Planet.

Quiet, please. You’re inside the Library Planet.

In the vast majority of imagined sci-fi worlds, the dearth of physical books usually just means everyone is “reading” in a different way. Well before we got e-readers in the real world, most of the reading in science fiction happened on screen. And now we’ve arrived at the future: we read from screens, every day, all the time. So what happens next, after and beyond reading from screens?

In Ernest Cline’s 2012 science fiction novel Ready Player One, much of Earth’s population interacts with a virtual reality system called the OASIS in which analog objects are duplicated in a digital realm, including old magazines and science fiction novels—these are recreated and “read” by one’s avatar while hooked into the virtual reality world.

Cline creates an in-universe reason for the retroactive obsession with analog: the programmer of the OASIS is a child of the 1980s. Not only does this conceit allow for characters to obsess over cultural touchstones that make sense to us right now, it also presents a reading dystopia with a little bit of hope for books. Despite the impoverishment of the “real world” in Ready Player One, Cline asserts an idealized digital realm where education and reading are not only encouraged but rewarded. Notably, Cline’s fictional virtual reality system relies on the idea of “haptics,” meaning digital objects create physical sensations for the person doing the interfacing: digital books feel like real books (this, of course, checks out with Konnikova’s idea that reading something with spatial “heft” is relevant to our ability to retain the information).

So, if all these books are preserved in the future with some sort of technology, and that technology isn’t horrible for us (like-mandated haptics in Ready Player One) then maybe the ubiquitous sci-fi reading dystopia isn’t as bad as first thought. Maybe the real question is one of preservation: does text survive into the future and how? Chris Rusbridge, the former director of the digital curation centre for JSTOR believes that the digital preservation of texts should be viewed not as ends in themselves, but instead, simply as ways we pass on the information:

“[I] view digital preservation as a series of holding positions, or perhaps as a relay. Make your dispositions on the basis of the timescale you can foresee and for which you have funding. Preserve your objects to the best of your ability, and hand them on to your successor in good order at the end of your lap of the relay.”

A Tale of Two Cities as a physical object may have been seen as an “antique” to Spock and Kirk in the 23rd century, but that doesn’t mean the information contained in the book—or humanity’s ability to retain the information—is lost. Maybe 23rd-century Dickens is just sitting at a different holding position than we’re familiar with now. If the digital preservation of texts taking place in our own lifetimes is only a “relay,” and we’ll end up with holographic, or “straight to brain” books in a far, far future, then maybe the physical book as antique won’t be such a terrible thing. Science fiction worlds often seem to want to correct for the loss of books (and reading), by populating the universe with enlightened, old fashion bookish characters like Spock, or the Doctor (from Doctor Who) or Alena Graedon’s protagonist Anana in The Word Exchange, or Asimov’s Hari Seldon or Ernest Cline’s Wade and Samantha. Bradbury famously had his “book people” memorize entire volumes in order to preserve books (though that actually happened in one of our real-world 20th-century dystopias). So perhaps people can will be “relays” and “holding positions,” too.

Science fiction’s preoccupation with futuristic reading achieves real depth in the 2014 novel The Word Exchange by Alena Graedon. Though not marketed as sci-fi, The Word Exchange is science fiction at its best, and in many ways, is the first time the reading dystopias of other science fiction narratives are sufficiently explained. In Graedon’s world, a tech company called Synchronicity Inc. buys the rights to every word in the dictionary, cornering the market on meaning as commodity. This happens as everyone’s e-reader gizmo, the Meme, is being replaced by a biologically integrated device called the Nautilus, which will allow all information to be directly fed into the brain.

Interviewing her last summer, Graedon mentioned researching “EEG” or electroencephalography technology to insure the science behind the Nautilus was at least plausible. She explained that the Nautilus “has organic components… and breaks the barrier between the technology and the person without necessarily breaking the skin… These biologically integrated technologies exist right now.” Not surprisingly, Graedon’s fictional reading apparatus backfires, resulting in wide-spread Word Flu, an aphasic pandemic that can lead to death. And the treatment for characters stricken with Word Flu? Reading the pages of an old-fashioned, physical book. So does Graedon believe the simple technology of the physical book the best we have?

“I’m not sure… but it is true that the kind of deep contemplation and abstract thinking that reading very long documents required and made possible, meant that people had to hold things and abstractions…so if you switch to things that have hypertext, you don’t have to remember things in quite the same way. So, a book is not a perfect technology, but I think the relationship between a person and a book—that dialectic—has lead to such extraordinary things that it’s hard for me to imagine that the replacement of that won’t have some sort of fallout.”

Imagining that fallout has been the calling of generations of science fiction writers, and will be so for generations to come. But from Asimov to Graedon, through all the dark and outlandish scenarios of science fiction’s collective imagination, a simple refrain seems to survive, in one iteration or another: “We have this device. It’s called a book.”

Ryan Britt

Ryan Britt is an essayist, critic, fiction writer, storyteller, and teacher living in New York City.