Drip Painting Was Actually Invented by a Ukrainian Grandmother... Not Jackson Pollock

Noah Charney on the Erasure of Women's Revolutionary Contributions to Art History

We’re supposed to think that Jackson Pollock invented drip painting, and with it the American branch of Abstract Expressionism. He did, didn’t he? So say Life and Time magazine and countless art history books and professors in dimly lit lecture halls, their brows tinted by the light from the projector, their words backed by the windy hum of its motor. The first drip, or all-around painting—made by the revolutionary technique of splattering and dripping paint on the fly while approaching the canvas from all angles, as it lay on the floor—was Pollock’s 1947 Galaxy. Wasn’t it?

It makes for a good story. Pollock was the macho, hard-drinking, Wyoming-raised cowboy of postwar American art—Hemingway with a paint bucket. Painting within the lines, the traditional way, wasn’t manly enough for a rebel like him. And he certainly made a name for himself. He remains one of the two most famous American painters, along with Andy Warhol. Americans, especially American men in the 1940s and 1950s, blazed trails and cast their shadows across the globe. This is the narrative that we’ve been taught.

And it’s all wrong. Or rather, it’s been airbrushed and skewed to fit this idea that men, particularly American men, are the trailblazers. This is so in just about every sphere, but in our case, we’re talking about art.

What Janet Sobel sparked, Jackson Pollock made famous.

Insert audible sigh and rolling of the eyes here.

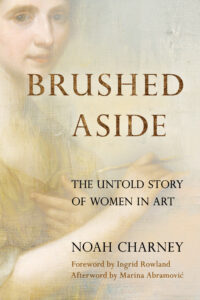

That’s what Brushed Aside: The Untold Story of Women in Art seeks to correct. For what has so often been overlooked or airbrushed out—brushed aside (pun intended)—is the role of women in the story of art. As artists, of course, but there are other books that showcase women artists (though in a different way than we will here). I’m interested in shining the spotlight on the overshadowed role of women in all aspects of art and its history. Not just as artists, but also as patrons, curators, influencers, critics, scholars, models, muses, and more. The result will, I hope, show a 360-degree view of women in art. So, how do we make the history of art into the herstory of art? Let’s begin by gently bumping Jackson Pollock off his pedestal.

Because all-over painting and the drip technique were actually invented by a Ukrainian grandmother.

Janet Sobel (1893–1968) was born as Jennie Lechovsky in a Jewish settlement in Ukraine. Her father was killed in a pogrom, the trauma of which prompted her to move to the United States, with her mother and three siblings, in 1908. A year later she married and went on to raise five children. It was decades later that she first picked up a paintbrush, when her then nineteen-year-old son passed his art supplies off to her. He’d won a scholarship to the Art Students League but didn’t plan to take it.

She tried to convince him to do so, to which he replied, “If you’re so interested in art, why don’t you paint?”

So paint she did. She was entirely untrained, and that has often been a good thing. In the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, it was considered a feather in one’s cap to be an “academic painter,” as the best artists were emerging from the early days of the academy system. But from the nineteenth century onward, being called an “academic painter” would be more of an insult, suggesting that, while you’ve got the certificate to show you’ve trained, you’re likely just continuing stale older traditions. Those who rock the boat and start revolutions aren’t those indoctrinated by academies, which have tended to be phallocentric and focus on the most celebrated revolutionaries, those who seem to best fit along the historical trajectory. Sobel experimented. She would squirt paint directly out of a tube, drip it with an eyedropper, even pull wet paint across the canvas using suction from a vacuum cleaner. She didn’t set her canvases on easels but laid them on the floor so she could attack them from all angles. As art historian Kelly Grovier wrote, “she assaulted the surface of canvases laid out on the floor, orchestrating a liquid lyricism of spills, splashes and spits, the likes of which had never before been seen.”

Sobel’s first drip painting was one she’d call Milky Way and finish in 1945—two years before Pollock “invented” drip painting. One of Sobel’s sons, Sol, immediately saw that his mother was onto something and became her annunciator—the one who acclaimed her talents. He wrote to the leading tastemakers of the time, including Marc Chagall, who, like Sobel, had fled antisemitic pogroms of his youth and was among the world’s most famous painters. But he also wrote to Sidney Janis, a wealthy clothing manufacturer and art collector who had been an advisor to MoMA (the Museum of Modern Art) since 1934 and who would be described today as an art world influencer. Janis saw Sobel as one of the great Contemporary American artists (along with others who were immigrants to America, including Willem de Kooning and Marko Rothko). He said that she would “probably eventually be known as one of the most important Surrealist artists in the country,” referring to her earlier formal style, before she turned to abstraction through drip painting. Janis included Sobel in an exhibition that toured the United States, “Abstract and Surrealist Painting in America,” which helped make her name, as well as helping her launch her first solo show in New York. Another hugely influential woman, Peggy Guggenheim, also included Sobel in a high-profile exhibition she promoted called “The Women.” But these were all in 1944 and featured Sobel’s work prior to her innovation of the drip technique.

Guggenheim was so impressed with Sobel that she also put on a solo show for her at her gallery, Art of the Century. That ran in 1946 and did include Milky Way. The leading art critic of the time, Clement Greenberg, wrote about visiting that exhibit with Jackson Pollock in 1946. Greenberg recalled the exhibit with a combination of dismissive misogynism toward Sobel and an admission that she had inspired Pollock. He wrote that he and Pollock had “noticed one or two curious paintings shown at Peggy Guggenheim’s by a primitive painter, Janet Sobel (who was, and still is, a housewife living in Brooklyn)….Pollock (and I myself) admired these pictures rather furtively….The effect—and it was the first really ‘allover’ one that I had ever seen—was strangely pleasing. Later on, Pollock admitted that these pictures had made an impression on him.”

A deeper look at this quote from Greenberg is revelatory of the sort of issues that have led to the marginalization of women in the story of art. Sandra Zalman wrote, in an article on Sobel, “Even as he selects Sobel as Pollock’s predecessor, Greenberg asserts that Pollock had already surpassed her.” Grovier notes Greenberg’s use of the word “furtive.” Whether intentionally inserted or a bit of a Freudian slip, it smacks of admission. This is the moment and the artwork that inspired Pollock to turn to “all-around” painting using the drip technique, using tricks that Sobel—a “Brooklyn housewife” as Greenberg dismissingly mentioned—had invented.

How do we make the history of art into the herstory of art?

It wasn’t just the predominately male media, and critics like Greenberg, that championed Pollock and never noticed Sobel. Camille Paglia, one of the most famous feminist scholars, described Pollock as the trailblazer in her book Glittering Images: A Journey through Art from Egypt to Star Wars: “During the summer of 1947, there was a major breakthrough: he invented his signature ‘drip’ style, which would transform contemporary art.” This is exactly what I was taught as an art history student. Later, Paglia would be the first to shine light on Sobel as the actual originator of this hugely influential style—but she likely didn’t know of her when she wrote her book.

Pollock was a hugely important figure and a wonderful painter. It’s not my goal to overtilt the axis of art history and topple icons. We must give credit where it’s due. One tip of the hat goes to the person who founded or invented a new style, technique, or genre—the true trailblazing revolutionaries. But it is just as remarkable to note who took that revolutionary spark and made of it a signal fire. What Janet Sobel sparked, Jackson Pollock made famous. Those are two different skill sets. Sometimes they inhabit the same person, sure. But in this case, the innovation goes to Sobel and the marketing and chain of influence goes to Pollock.

Sobel receded from view almost as swiftly as she’d emerged from obscurity due to four ruinous factors. First, in 1946, the same year of her big solo show, she subjugated her career to her husband’s. The family moved to rural New Jersey, which was where her husband’s costume jewelry business was based. Sobel didn’t know how to drive and therefore couldn’t access the heart of the art world, New York City.

Second, Sobel developed, or first took note of, a rare allergy that she had to an ingredient in the paint she was using. She switched to other media, including crayons, but could no longer paint, and so could no longer drip. Third, Peggy Guggenheim, her biggest supporter, left New York and moved to Europe, settling in Venice—even further from Sobel’s circle of access. Finally, while Sidney Janis wrote in praise of her work, she lacked a high-profile writer to help promote her work. There was no Clement Greenberg as her annunciating angel. She wound up as a footnote for far too long, her spotlight, like her career, too brief. It’s only recently that scholars like Kelly Grovier and Sandra Zalman have pulled her back into the light. But they are rare discoverers of this lost artist. There’s not a single book about her in print.

I take issue with the fact that Sobel is almost completely forgotten, unknown, overshadowed by Pollock. And so are hundreds of important women who have influenced the story of art. My hope is that Brushed Aside: The Untold Story of Women in Art will go some way to correcting this oversight—one born of patriarchal prejudice—to celebrating the Janet Sobels of the art world.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Brushed Aside: The Untold Story of Women in Art by Noah Charney. Copyright © 2023. Used by permission of the publisher Rowman & Littlefield. All rights reserved.

Noah Charney

Noah Charney is the internationally best-selling author of more than a dozen books, most recently, The Devil in the Gallery: How Scandal, Shock, and Rivalry Shaped the Art World, and including The Collector of Lives: Giorgio Vasari and the Invention of Art, which was nominated for the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in Biography. He is a professor of art history specializing in art crime, and has taught for Yale University, Brown University, the American University of Rome, and the University of Ljubljana. He lives in Slovenia.