Dinner With A Dictator: What Joseph Stalin Ate

Witold Szabłowski on the Culinary Habits and Preferences of the Soviet Strongman

He lays a hand on my arm. He looks me in the eyes, and then, resignedly, he looks off toward the mountains. Then at me again. “I killed a man, Witold, do you understand?” Again he looks away, at the sky; clearly, talking to me is not bringing him the kind of relief he might have been hoping for. “He was standing next to me, roughly as far away as my brother is now.” And he points at his brother, who is sitting quite close by. “And I shot him dead, you see?”

Then he waits for me to say something.

I don’t know what to say. And I don’t know how to enter into the mood of this conversation. It’s 2009 and in the place we’re sitting, just a year earlier, the Russian invasion of Georgia was under way. I’m wondering how to get myself out of this pickle. I’m on my own, drunk, among some Georgians the size of oak trees; we’re surrounded by mountains I can’t name. A while ago they told me they’re descended from princes—as I already know, here in the Caucasus there’s often someone claiming to be royalty.

But then they started telling me that their great-uncle was Stalin’s brother—that’s an advance on the usual story, because although everyone in Georgia is proud of Stalin, I’ve never met any of his cousins before.

Especially since I know that Stalin’s brothers died as soon as they were born.

But now they’re telling me about the Russian soldiers they killed during the recent war between Russia and Georgia. Four big, beefy guys, with necks like tree trunks.

Stalin’s one and only culinary extravagance in those days was a bathtub full of pickled gherkins.It’s all too much for me. I’m trying to devise an escape plan.

But before I can make a move, one of the men lunges at me. He pins me down. And holds on.

*

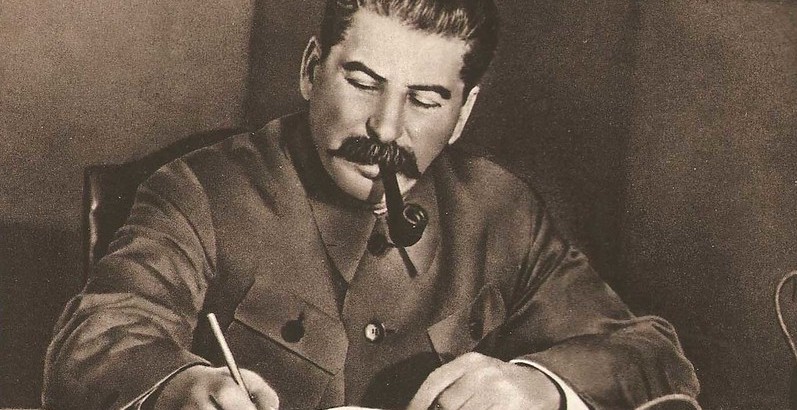

He couldn’t stand cooking. When he was a child, his mother had various jobs. One of them was as a cook. Supposedly that was why for the rest of his life Joseph Stalin hated the smell of food being cooked, and had all the kitchens serving his dachas and houses built at a distance—which was true of the dacha in New Athos that I visited in Abkhazia.

When he and his comrades were exiled to Siberia by the tsar, they agreed that they would share all the duties equally—the cooking, the cleaning, and the procurement of food. But it soon became clear that Stalin had no intention of cooking or cleaning. He just went hunting and fishing.

Yakov Sverdlov, who was in exile with Stalin, was particularly angry with him. “We were meant to cook the dinners ourselves,” recalled Stalin years later. “At the time I had a dog, and I named him Yashka, which naturally displeased Sverdlov, because he too was Yashka [the diminutive of Yakov]. After dinner Sverdlov always washed the spoons and plates, but I never did. I ate my food, put my plates on the floor, the dog licked them, and everything was clean.”

Toward the end of their exile, when they were living with a third communist, Lev Kamenev, whenever it was time to wash the dishes, Stalin would flee the house.

After the revolution he ate with his wife, Nadezhda Alliluyeva, at the Kremlin canteen, which in those days had the reputation of being one of the worst in Moscow.

The French writer and communist Henri Barbusse visited Stalin shortly after Alliluyeva’s suicide and said of his living conditions: “The bedrooms are as simply furnished as those of a respectable second-class hotel. The dining room is oval in shape; the meal has been sent in from a neighboring restaurant. In a capitalist country a junior office clerk would turn up his nose at the bedrooms and complain about the fare.”

According to Vyacheslav Molotov, who headed the Soviet diplomatic corps, Stalin’s one and only culinary extravagance in those days was a bathtub full of pickled gherkins.

*

Let’s go back to my meeting in the mountains.

It all started innocently enough. I was in Gori, Stalin’s birthplace, in the beautiful mountains of central Georgia. I was driving around the picturesque neighboring villages to find the local wine producers that used to supply the Kremlin cellars—the only wine Stalin drank was Georgian.

“Wine producers” sounds very grand. In fact, every self-respecting farmer in Georgia has some vines and reliably makes fantastic wine, as well as a sort of brandy, often 70 percent proof, known as chacha. It was a cottage industry of this kind that I was looking for.

The Georgians’ boundless hospitality made my work impossible—because how can you get any work done when everyone you visit brings out the wine and the chacha and has to treat you before they’ll answer your questions? After half an hour you’re too well oiled, and besides, the day is still young, the nature is beautiful, your host is friendly, so why on earth do any work? And then once we’d had a drink, every single host told me that a plane used to fly from Moscow just to fetch Stalin’s wine. What’s more, every other host swore he had documents to prove it, and two of them even showed them to me, though first of all, they were in Georgian, and second, I was too tipsy to understand them or remember anything about them.

So I’d been having a jolly time driving around Gori for several days when I encountered the first of the Tarkanishvili brothers. He was in his off-road vehicle, just leaving the allotment he’d inherited. He had a bit of a paunch, and he was wearing a cap with the logo of an American basketball team. When he heard what I was looking for, he told me, in broken Russian, to call him that evening.

“You won’t regret it,” he said. “My family has a better story about Stalin than anyone else. In all of Gori.”

I didn’t need to be told twice.

*

The following evening the brothers drove me into the mountains. They tossed into the back of their pickup truck a sheep that they’d butchered for shashliks. On the way all four of them started talking over one another:

“As a true son of our land, Stalin created a ‘little Georgia’ for himself in Russia. And did what he could to be surrounded by Georgians. Best of all, family.”

“Your family won’t betray you because they know that if they did, they’d have nowhere to come home to.”

“That’s why he kept all his sidekicks, those Molotovs and Khrushchevs, on a short leash. They knew that one false move and blam! You’re gone, grand Mr. People’s Commissar. Only the Georgians had peace.”

And so our journey flew by. On the way the gentlemen told me about their sports successes: one was a wrestling trainer, another trained weight lifters. They managed competitors at the international level.

By the time we reached the mountains, we were very well acquainted and fairly well canned, and the brothers finally decided to tell me about Stalin.

“For many years it was a secret—our father told us the story of Uncle Sasha, but he always stressed that we weren’t to repeat it to anyone…”

“Which was pointless, because in Georgia everyone knew anyway…”

“Our great-uncle Alexander, or Sasha, was Stalin’s brother. Don’t look at me like that! He was his brother. Boys, he doesn’t believe us…”

“He will soon. Listen, Witold. Stalin’s mother worked for our great-grandfather as a cook. And once or twice he and she…well, you know, they did what guys and gals do. When he found out she was pregnant, he married her off to the illiterate cobbler Vissarion.”

“Vissarion knew how to write! But he drank like a fish.”

“I heard he couldn’t count to three. Whatever the case, he had no idea what was going on. And when he realized, he took to beating the kid badly—really badly.”

Stalin himself knew how to make pretty good shashliks—he’d learned that at home in Georgia.“Little Stalin was always running away to spend time with our great-uncle Sasha, who was the same age as him, and who was also the son of our great-grandfather. They became friends, and many years later Great-uncle Sasha became Stalin’s cook and food taster at the Kremlin. Well, look at that—he still doesn’t believe us.”

It’s true. I didn’t believe a single word.

*

For many years Stalin, following Lenin’s example, didn’t attach much importance to food—those men of the revolution were sustained by something else. Just like Lenin’s wife, Nadezhda Sergeyevna Alliluyeva was clueless about cooking. Whereas Stalin himself knew how to make pretty good shashliks—he’d learned that at home in Georgia.

But when Alliluyeva committed suicide in 1932—some say she couldn’t take it when she realized her husband had deliberately starved Ukraine—Stalin wanted nothing to do with shashliks or any other food. He became withdrawn and sank into a depression. Like others in the government he ate at the Kremlin, in the canteen. For the children who remained with him, the state hired a cook, apparently a rather average one.

Many years later Vyacheslav Molotov recalled that the food cooked for Stalin “was very simple and unpretentious.” In the winter he was always served meat soup with sauerkraut, and in the summer, fresh cabbage soup. For a second course there was buckwheat with butter and a slice of beef. For dessert, if there was any, cranberry jelly or dried fruit compote. “It was the same as during an ordinary Soviet summer vacation, but throughout the year.”

The brothers went on to tell me several stories about their great-uncle, and then about the 2008 war between Russia and Georgia. The oldest one, Rati, really did lunge at me. But it turned out he just wanted to hug me and raise a toast to Poland’s president, Lech Kaczyński—the Georgians adore him because he defended their country against Russian aggression. For them, the brothers told me, Kaczyński is as great a hero as Stalin.

The next morning, once we had sobered up enough for one of them to be able to drive, they drove me back to Gori. We said goodbye with less enthusiasm, as you do when you have a hangover, but we promised one another we’d be friends for the rest of our lives. And although I haven’t seen them since, I remember our meeting with great fondness. But for many years I filed away the story about the great-uncle who cooked for Stalin along with the myths and fairy tales that people sometimes tell me on my travels.

I was very much mistaken. Great-uncle Sasha really did exist. More than that, he genuinely revolutionized Stalin’s eating habits; he got him out of the depressing Kremlin canteen and reminded him of the wonders and vitality of Georgian cuisine, as well as the virtues of the Georgian feast with friends. Stalin made use of these lessons to the end of his days.

Was he really the great-uncle of the four brothers who treated me to lamb shashliks that night? That I don’t know and am likely never to find out—I have tried to find them again, to no avail.

__________________________________

Excerpted from What’s Cooking in the Kremlin: From Rasputin to Putin, How Russia Built an Empire with a Knife and Fork by Witold Szabłowski, translated from the Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones. Copyright © 2023. Available from Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.