Doubting Shakespeare’s Identity Isn’t a Conspiracy Theory

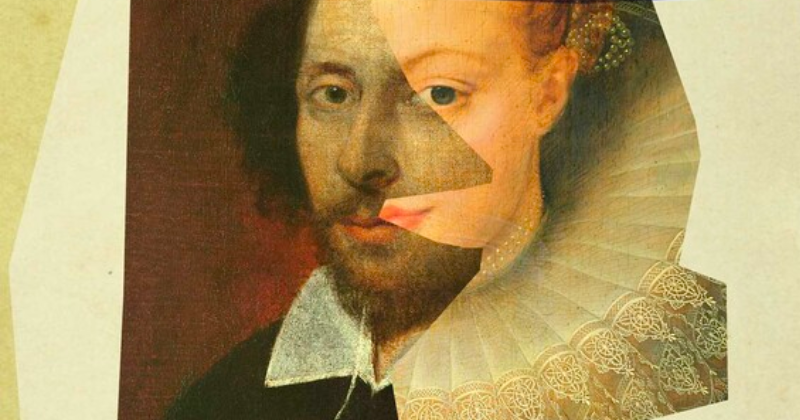

Elizabeth Winkler Argues the Mystery Behind the God of Iambic Thunder Is Part of the Thrill

The Shakespeare authorship question—the theory that William Shakespeare might not have written the works published under his name—is the most horrible, vexed, unspeakable subject in the history of English literature.

Among Shakespeare scholars, even the phrase “Shakespeare authorship question” elicits contempt—eye-rolling, name-calling, mudslinging. If you raise it casually in a social setting, someone might chastise you as though you’ve uttered a deeply offensive profanity. Someone else might get up and leave the room. Tears may be shed. A whip may be produced. You will be punished, which is to say, educated. Because it is obscene to suggest that the god of English literature might be a false god. It is heresy.

This is curious, because many of our greatest writers and thinkers have suspected that the name was indeed a pseudonym for a concealed author. “I am ‘sort of’ haunted by the conviction that the divine William is the biggest and most successful fraud ever practiced on a patient world,” wrote Henry James.

“We all know how much mythus there is there is in the Shakspere question as it stands to-day,” Walt Whitman noted. Whitman, the poet of democracy, was no snob, but he was convinced that there was another mind behind the plays.

Mark Twain agreed. “So far as anybody actually knows and can prove, Shakespeare of Stratford-on-Avon never wrote a play in his life,” he wrote. “All the rest of his vast history, as furnished by the biographers, is built up, course upon course, of guesses, inferences, theories, conjectures—an Eiffel Tower of artificialities rising sky-high.”

For Vladimir Nabokov, the mystery inspired a poem. “You easily, regretlessly relinquished the laurels… concealing for all time your monstrous genius beneath a mask,” he wrote. “Reveal yourself, god of iambic thunder, you hundred-mouthed, unthinkably great bard!”

I’ve come to see the authorship question as a kind of metaphor for the problem of history—of how we know what we think we know about the past. It’s also a metaphor for the problem of authority—of who has the authority to determine the truth about the past.

In England in the summer of 1964, the question came before the courts. Miss Evelyn May Hopkins had died, leaving a third of her inheritance to the Francis Bacon Society for the purpose of finding the original manuscripts of Shakespeare’s plays. The aim of finding the manuscripts was to prove that Francis Bacon, the Elizabethan philosopher and statesman, was in fact the author of the works attributed to Shakespeare. Her heirs were not pleased. Seeking to reclaim their inheritance, they brought a suit against the society, arguing that Miss Hopkins’s bequest be overturned on the grounds that the search would be a “wild goose chase.” To support their case, they solicited the testimony of scholarly experts.

Counsel for the next of kin “described it as a wild goose chase; but wild geese can, with good fortune, be apprehended,” observed the Right Honorable Richard Wilberforce, a justice of Her Majesty’s High Court. Many discoveries are unlikely until they are made, he pointed out: “one may think of the Codex Sinaiticus, or the Tomb of Tutankhamen, or the Dead Sea Scrolls.” Wilberforce was a stolid Englishman, a former classics scholar at Oxford who rose through Britain’s legal ranks to become a senior Law Lord in the House of Lords and a member of the Queen’s Privy Council. Having reviewed the evidence submitted to the court, he summarized it as follows:

“The orthodox opinion, which at the present time is unanimous, or nearly so, among scholars and experts in sixteenth and seventeenth century literature and history, is that the plays were written by William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon, actor.”

However, Justice Wilberforce continued, “The evidence in favor of Shakespeare’s authorship is quantitatively slight. It rests positively, in the main, on the explicit statements in the First Folio of 1623”—the collection of Shakespeare’s plays, which turns 400 this year—”and on continuous tradition; negatively on the lack of any challenge to this ascription at the time” of the First Folio’s publication. Furthermore, the justice found, “There are a number of difficulties in the way of the traditional ascription … a number of known facts which are difficult to reconcile.”

For instance, when Shakespeare died, he left detailed instructions for the distribution of his assets but mentioned no poems, plays or manuscripts of any kind. At his death, only half of the plays had been published. Did he have no concern for their preservation? Why didn’t he say anything in his will about his poems—several major narrative poems, 154 sonnets? “[S]o far from these difficulties tending to diminish with time, the intensive search of the nineteenth century has widened the evidentiary gulf between William Shakespeare the man, and the author of the plays,” noted the justice.

He went on to consider the testimony of the scholarly experts. Kenneth Muir, King Alfred Professor of English literature at the University of Liverpool, supported the plaintiffs, Miss Hopkins’s aggrieved heirs. He considered it “certain” that Bacon could not have written the works of Shakespeare.

Scholars seek approval from leaders in their fields—department chairs, journal editors, peer reviewers. They fear rejection.Hugh Trevor-Roper, Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford, departed slightly from his English literature colleagues, taking what the justice deemed “a more cautious line.” Though Professor Trevor-Roper “definitely does not believe that the works of ‘Shakespeare’ could have been written by Francis Bacon, he also considers that the case for Shakespeare rests on a narrow balance of evidence and that new material could upset it; that though almost all professional scholars accept ‘Shakespeare’s’ authorship, a settled scholarly tradition can inhibit free thought, that heretics are not necessarily wrong. His conclusion is that the question of authorship cannot be considered as closed.”

Justice Wilberforce agreed. The question was not closed. The evidence for Shakespeare was too slim, the problems too many. The scholars might be wrong. Even if Francis Bacon was unlikely, new material might show someone other than Shakespeare to have been the author.

Whoever wrote them, the manuscripts of Shakespeare’s plays had never been found. Their discovery would be “of the highest value to history and to literature,” Wilberforce proclaimed. Indeed, he added, to the consternation of the plaintiffs and the Shakespeare scholars, “the revelation of a manuscript would contribute, probably decisively, to a solution to the authorship problem, and this alone is benefit enough.”

Miss Hopkins’s bequest to the Francis Bacon Society was upheld.

The 1964 trial did not rule directly on the authorship question—Did he or didn’t he?—but it raised the problem of authority. Were the Shakespeare scholars called to testify to the traditional attribution, in support of Miss Hopkins’s irritated heirs, infallible? Was it possible that heretics— nonspecialists—might be right?

Behind the observations that “a settled scholarly tradition can inhibit free thought” and “heretics are not necessarily wrong” lay the whole history of knowledge: of truth perverted by confirmation bias and groupthink; of scholars clinging to outdated theories, contemptuous of ideas that threaten their authority; of long-held certainties rendered quaint by new knowledge; of entire fields revolutionized by heresy. The trial had the effect of displacing the authority of the scholars, making them mere witnesses—biased, partial—and putting the truth in the hands of the court, which concluded, in fact, that the truth was not certain.

*

In 2023, questioning an expert’s authority feels exceedingly uncomfortable. It puts people in mind of COVID deniers and other bad actors who have weaponized “just asking questions.” We’re generally better off trusting experts. At the same time, it remains true that authorities aren’t always right. Geologists ridiculed Alfred Wegener’s theory of continental drift for decades before fully accepting it. Historians insisted that Thomas Jefferson didn’t father children by his slave Sally Hemings—until DNA evidence proved that he did.

Academia is vulnerable to groupthink, a phenomenon of social psychology in which a group maintains cohesion by agreeing not to question unproven core assumptions and excluding anyone who deviates from group doctrine. Scholars seek approval from leaders in their fields—department chairs, journal editors, peer reviewers. They fear rejection. These dynamics encourage conformity. Though Shakespeare scholars have interpretive differences, they adhere to a fundamental set of common beliefs, their core belief being the traditional theory of authorship.

And yet in private, some Shakespeare scholars quietly admit doubts. “Yes, of course ‘Shakespeare’ could have been a pen name or a scam or a committee of Bacon/Marlowe/Oxford/ Henry Neville/etc.,” a professor at an Ivy League university wrote to me, listing some of the alternate authorship candidates.

As we exchanged emails, it seemed this professor was perfectly fine with letting Shakespeare be seen as the author, even if he knew it might not be true. “I think we’ve got a big enough task in figuring out what the plays are doing in themselves,” he explained, although I wondered if knowing more about their author wouldn’t help with that.

Shakespeare is a mystery that scholars cannot explain. “Shakespeare’s knowledge of classics and philosophy has always puzzled his biographers,” admitted the scholar E.K. Chambers. “A few years at the Stratford Grammar School do not explain it.” Others have tried to resolve the puzzle by downplaying Shakespeare’s erudition. The plays merely “looked learned,” especially “to the less literate public,” insisted Harvard’s Alfred Harbage.

But the plays have sent scholars writing whole books on the law in Shakespeare, medicine in Shakespeare, theology in Shakespeare. Shakespeare and astronomy. Shakespeare and music. Shakespeare and Italy. Shakespeare and the French language. “The creative artist absorbs information from the surrounding air,” Harbage assured his readers, floating a theory of education by osmosis. Throwing up his hands, Samuel Schoenbaum, one of the 20th-century’s leading Shakespeare scholars, resolved the conundrum by explaining that “Shakespeare was superhuman,” an explanation that is, of course, no explanation at all.

The mystery inspires our awe, is part of what we love about Shakespeare, is part of what, in fact, makes Shakespeare Shakespeare. Shakespeare satisfies our need for the sacred, for something that surpasses our ability to understand. In the West generally and in Britain in particular, he functions as a secular god. Pilgrims began flocking to Stratford-upon-Avon in the 18th-century to pay homage to the poet.

They dropped to their knees at “The Birthplace,” the purported site of his nativity. They cut “relics” from the local mulberry tree, like pieces of the true cross. They sang odes to Shakespeare: “Untouched and sacred be thy shrine, Avonian Willy, bard Divine!”

There is nothing inherently outrageous about pseudonymity. Literary history is full of writers who concealed their authorship, and the Renaissance was a particularly great age of assumed names.By the mid-19th century, English departments began to develop, and ideas about Shakespeare that were enshrined during this period of extreme veneration have been passed down from one generation of scholars to the next.

This may be why the authorship question has taken on the fanatical, emotional veneer of a religious war. No one takes kindly to the denial of his god. Shakespeare scholars—which is to say the Shakespearean priesthood—decry the snobbery in the view that a glover’s son could not have written the works of Shakespeare. (Was not a carpenter’s son the savior of mankind?) In the same breath, they resent the affront to their apostolic authority by what they see as a rabble of amateurs and cranks.

In 2011, Professor Stanley Wells declared, “It is immoral to question history and to take credit away from William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon.” Immoral to question history— when inquiry is the very basis of the historical discipline! Instead of engaging with the arguments, scholars launch these ad hominem attacks. I’ve sat down with eminent Shakespeare scholars who couldn’t offer alternate explanations for evidence that Shakespeare may not have been who he seemed because they didn’t even seem familiar with it.

But there is nothing inherently outrageous about pseudonymity. Literary history is full of writers who concealed their authorship, and the Renaissance was a particularly great age of assumed names. Some writers scrambled their names into anagrams. (Nicholas Breton appeared as “Salohcin Treboun.”) Others used obvious pseudonyms like “Democritus,” who explained that the name allowed him “to assume a little more liberty and freedome of speech.”

A writer known as “Martin Marprelate,” who criticized the Church of England, had a natural need to conceal his identity. Satirists crafted humorous names like “Simon Smell-knave” and “Thomas Tell-troth.” Meanwhile, some writers used false attribution, ascribing their work to another, living person. As the scholar Marcy North explains, false attribution was “popular and marketable,” allowing authors to cultivate a recognizable brand while remaining anonymous.

The authorship question has engaged historians, sociologists, psychologists, physicists, philosophers, lawyers, theater directors, and Supreme Court justices. “Academics err in failing to acknowledge the mystery surrounding ‘Shake-speare’s’ identity,” Mortimer Adler, professor of philosophy at the University of Chicago, wrote. “They would do both liberal education and the works of ‘Shake-speare’ a distinguished service by opening the question to the judgment of their students, and others outside the academic realm.”

The late Justice John Paul Stevens agreed: “I think the evidence that he was not the author is beyond a reasonable doubt.” Shakespeare professors rarely engage. This paradigm may be shifting. At York University in Canada, a professor of theater named Don Rubin created a course on the authorship question. His colleagues in English scoffed, but there was a waiting list every year. By 2018, the University of London began offering an online course called Introduction to Who Wrote Shakespeare.

Arguments about the past are a fundamental feature of academic freedom and democratic debate. There is nothing dangerous or “immoral” in questioning Shakespeare. In fact, there is something delightfully Shakespearean about the Shakespeare authorship question. The plays themselves are full of mistaken identities, disguises, and appearances that are never quite what they seem. For those who are willing to forgo the comforts of certainty, this is the greatest drama the bard never wrote.

__________________________________

Adapted from Shakespeare Was A Woman and Other Heresies: How Doubting the Bard Became the Biggest Taboo in Literature by Elizabeth Winkler. Copyright © 2023 by Elizabeth Winkler. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.