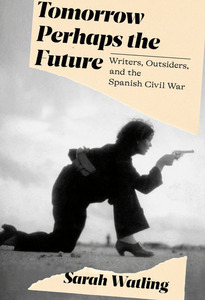

Why the Spanish Civil War Mattered to Writers on Distant Shores

Sarah Watling Looks at the Role Literature Played in the Fight Against Fascism

The Spanish war began in July 1936 when a group of disaffected generals—including Francisco Franco, who would emerge as their leader— attempted to launch a coup against their country’s elected government. The reaction of foreign powers was significant from the start.

Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany offered decisive material support to Franco’s side (the nationalists) while the Republican government received from its fellow democracies in France, the United States and Great Britain only a queasy refusal to intervene.

As the Republic battled to survive this well-resourced attack, relying on a tenacious popular resistance to the military takeover and on arms from Soviet Russia and Mexico, many observers understood the war as an opportunity to halt the global advance of fascism: one that their own governments seemed loath to take up.

Some months in, Nancy Cunard challenged her fellow writers to make public statements on the war in an urgent call that framed things like this:

It is clear to many of us throughout the whole world that now, as certainly never before, we are determined or compelled, to take sides. The equivocal attitude, the Ivory Tower, the paradoxical, the ironic detachment, will no longer do.

This was where the Spanish Civil War began to matter to me. It happened that, when I first found this eye-catching statement, I was living through an era of national and international upheaval that made Nancy’s 80-year-old challenge snatch up my attention.

It was possible, in her day, to see democracy as a teetering edifice, a system that had outlived, even failed, its potential. Alternatives vied for dominance. The Great Depression in America, that “citadel of capitalism,” had not only destabilized economies around the world but shaken faith in the capitalist system itself—proving, to some minds, the validity of the Marxist theory that had predicted its collapse.

The twenties and early thirties had seen military dictators or non-democratic forms of government gain the upper hand in a raft of countries: Hungary, Poland, Yugoslavia, Romania, Japan, Portugal, Austria, Bulgaria, Greece and, of course, even earlier, Russia. By 1936, Germany and Italy had been governed by fascists for years. Their regimes found plenty of sympathizers in countries shaken by the First World War and ensuing Depression.

The British Union of Fascists, for instance, was already almost four years old. Nor was fascist aggression on the international stage something new. Italy had invaded Ethiopia in 1935; Germany was openly remilitarizing—something forbidden by the terms of the peace imposed at the end of the First World War. For some, the great dichotomy of the 1930s was provided by fascism and communism. For many others (including those who weren’t convinced of a meaningful difference between the two), Spain was perhaps simpler still: fascism or opposition to fascism.

By my day it had become fairly common to hear people drawing dark parallels with the 1930s: that decade in which Mussolini and Hitler crushed opposition and raised their armies, and Franco took over Spain, and “Blackshirts” marched in the streets of London. We thought we knew these facts, but it seemed they were losing their power to terrify or forewarn; that acknowledging them belonged to an old tyranny of decency and truth that others were ready to throw off.

It’s an absurd kind of grandiosity, in a way, to relate the darkest past to your own moment and its preoccupations. Yet I felt many of the things I had taken for granted dropping away around the time I first started reading about Nancy Cunard. Democratic processes, mechanisms of justice, truth itself: all were under renewed threat.

My country seemed a less moderate, less peaceful place than I was used to, and newly emboldened extremists were taking eagerly to the public stage. Inequalities of wealth and opportunity were widening. The urgency of the climate crisis felt increasingly clamorous. It was difficult not to simply feel hopeless; pinioned into a narrow space of outraged despair.

And yet, it was quite convenient to have so much out in the open. It was something to respond to. It gave Nancy’s uncompromising position a certain appeal—even offered, perhaps, a kind of permission. I kept remembering a feminist demonstration I had taken part in years before, when I was 21. Meeting friends in a park afterwards, one of them had punctured our exultant mood: the turn-out I’d bragged of was more or less meaningless, he opined, an act of preaching to the choir. What was the point when everyone on the march was already persuaded?

Of all the defeats in history, perhaps only Troy has been as well served by literature as Republican Spain was during and after the ascension of Franco.By 2019—a year in which, though abortion rights had just been extended in Ireland, the UN Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights could describe US policy on abortion as “gender-based violence against women, no question” and the anti-feminist, far-right Vox party made unprecedented gains in Spain, raising the uncomfortable specter of Franco—the response I should have made was becoming clearer to me. My 21-year-old self had marched to give notice of her resistance. There was nothing to be gained by trying to understand the point of view we were protesting (that the way women dressed could provoke rape), but much to be risked from letting that idea exist in the world unchallenged.

Nancy’s “taking sides” has an air of immaturity about it, perhaps precisely because of the playground training most of us receive in it. So much prudence and fairness is signified by resisting these easy allegiances, by seeing “two sides to every story”—a terminology that tends to imply that truth or moral superiority can only ever exist in not choosing either one. And it was becoming clear that polarization serves the extremes best of all.

But something about Nancy’s construction spoke to me. It suggested that there is power in the act of taking a side; that there are moments on which history rests, when nuance or hesitation (perhaps or tomorrow) will prove fatal, when it is vital to know—and to acknowledge—which side you are on.

The worst times can take on an appearance of simplicity and war is exactly the kind of aberration that removes options, leaving the single choice of one side or another in its place. Yet when Nancy and thousands of other foreigners to Spain acted voluntarily in support of the Spanish Republic, they made their beliefs public. Their actions proposed the worst times as periods of opportunity, too: invitations to reclaim principles from the privacy of our thoughts and conversations and ballot boxes, and make them decisive factors in the way we live and act.

This is why my book is not about the Spanish experience of the war, but rather about the people who had the option not to involve themselves and decided otherwise.

Writers are good for thinking through. I was interested in the question of critical distance—whether it is always possible or even, as I’d instinctively assumed, always desirable—and I could think of no better individual to shed light on this than a writer (or intellectual) in war-time.

But people from all walks of life understood the Spanish war as a question, a provocation that demanded an answer. Thousands from across the world volunteered on behalf of the Republic, going so far as to travel to the country as combatants and auxiliaries. Others declared themselves through campaigning and fundraising. Martha Gellhorn defined herself as “an onlooker”: I wanted to explore, too, the experience of people whose commitment drew them closer to the action.

Alongside her in this book are the British Communist Nan Green and her husband, George, who wrenched themselves from their children to volunteer with medical and military units in Republican Spain. There is a young African American nurse named Salaria Kea who saw her service there as a calling. There is one of the boldest photographers to contribute to the memory of the war: Gerda Taro, a refugee from Germany for whom the fight against fascism was personal.

They left their own accounts of the conflict, whether through images or text, and following their stories taught me much about how historical narratives are formed in the first place; why leaving a record can be one of the most instinctive, and contested, human impulses.

They went because, as Martha Gellhorn put it, “We knew, we just knew that Spain was the place to stop Fascism.”

When I went looking for Salaria Kea, the negotiations and challenges her story had undergone became as interesting to me as the missing pieces. A woman of color deemed a political radical, a nurse and not a writer: hers was a voice that rarely received a welcome hearing. My book voices many of my questions, but with Salaria so much was unclear that I realized I could only tell her story by narrating the pursuit and leaving the questions open.

“Rebels,” like Franco, turn military might against the government they’re meant to serve. But I found that all the people I chose to follow fulfilled the word’s other definition, of those who “resist authority, control, or convention.” I wanted to know why they believed that the moment had come, with Spain, for taking sides.

Or, rather, I wanted to know how they recognized the Spanish war as the moment for doing something about the way their present was heading, and what “taking sides” had meant in practice. I wanted to know whether Nancy really thought the mere act of declaring a side could make a difference, as she suggested when she put out that urgent call. I wanted to know why she had addressed it specifically to “Writers and Poets.”

The Spanish war is often remembered for, and through, its writers—and notably writers from outside the country. Of all the defeats in history, perhaps only Troy has been as well served by literature as Republican Spain was during and after the ascension of Franco, who would eventually rule in Spain for almost forty years. Countless novels and memoirs, a handful of them the greatest books by the greatest writers of their generation; reams of poetry, both brilliant and pedestrian, have preserved the memory of its cause.

As I read, I began to think that their authors’ position had something to say about the nature of writing itself. It seemed significant that each of the writers in this book saw themselves, whether at home or abroad, as an outsider. If not belonging was a fundamental part of that identity, taking sides on Spain only crystallized a series of pressing questions about the purpose and privileges of writers.

The 1930s was a decade of art colliding with politics, of artists determining to marry the two. Presented with the trauma of the Great Depression, the unavoidable phenomenon of Soviet Russia and the spread of fascism, there were journalists and poets alike who sought new modes and new material. Writers questioned their obligations to society, asked what art could achieve; they interrogated the intellectual life to expose its value and its limitations.

The list of foreigners who spent time in Spain during the war reads like a roll call of the most celebrated voices of the era: think of the Spanish war and I imagine you think of Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell, perhaps Stephen Spender, John Dos Passos, W. H. Auden. Delve a little further and you will find a far greater array of authors, including writers who were female, writers of color, writers who did not write in English (though the wealth of Spanish-language literature falls beyond the scope of a book interested in the outsiderness of writers).

They went because, as Martha Gellhorn put it, “We knew, we just knew that Spain was the place to stop Fascism,” or because they believed in the liberal project of the Republic and wanted to raise awareness of its plight, or because they wanted to observe, or even participate in, the cause célèbre of the moment. They saw history coming and went out to meet it.

__________________________________

From Tomorrow Perhaps the Future by Sarah Watling. Copyright © 2023 by Sarah Watling. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.