He woke up early, unusual for him, and got out of bed with cheerful enthusiasm.

He headed to the tap to wash his face and freshen his breath with minty toothpaste but discovered the water had been shut off. God! When had they come? Did they never sleep!

Then he remembered that he hadn’t paid the utility bill this month. But how could he, if paying for water meant not paying for something else?

He could do without electricity for a month, without water for a month, without a phone for a month. He could stand the shopkeeper’s frustrations and the landlord’s provocations, and he swore, if the government allowed people to sleep on the streets, he could do without a house for a month, too. With that, he put ‘house’ on his ‘marginal list’, the list of things he could do without.

He tried not to give this trivial, inconsequential thing the pleasure of spoiling his good mood; he overcame it. He and his family always kept extra water just in case, and when that ran out, probably about two days into the shutoff, he could run a hose from his neighbour’s house.

‘Fill up a bucket and fast,’ he shouted to his son. ‘I need to shower and get out of here.’

He shut the bathroom door behind him, even though it was ridden with holes.

Cold water cascaded over his body and he felt invigorated. He wished the day would skip over the next two hours, cast them aside or return to them later. Either would be fine; what he wanted was to shut his eyes, open them, and find that it was nine o’clock, time to start his new job.

From that day forward he wouldn’t have to wait for his brothers to send money sporadically from abroad; he wouldn’t change his route to avoid the shopkeeper, or the butcher, or the neighbour who lent them part of his pension.

Their meals wouldn’t follow the rule of ‘here one day, gone the next, the third day only crumbs’; his children wouldn’t go to bed without dinner, without even a little glass of milk.

‘No no no… get out of here, boy… Mohammed, c’mere c’mere, your brother shoved the door. Ali grab that boy there, the door’ll fall on his foot…’

The bathroom door was nothing more than a sheet of zinc with partially patched holes, but it mostly concealed whoever was behind it.

He got dressed without rinsing all the soap off his body,and swore that he would replace this corroded piece of zinc they generously called a door.

He made some tea, adding just a small pinch of sugar as usual. He put his faith in God, praised His name, and went to leave, but…

The front door! What was with the door? He tried to open it, pushed harder and harder, but it wouldn’t budge. It was a double door, and one side was shorter than the other.

‘Damn this warped door!’ he said scornfully. ‘Mohammed, I’ve told you a hundred times not to shut this blasted door so hard… when you slam it, it sticks like this.’

After a torrent of angry words he finally managed to open the door, with a screech heard by half of the neighbourhood. He looked down, and saw that the right sleeve of his freshly pressed shirt was now completely wrinkled.

But… no matter. He didn’t want anything to spoil his mood. He tried to smooth the fabric with his other hand and kept walking. A bus was waiting and he quickly stepped aboard; he didn’t want to be late for his first day.

‘Get everyone in the doorway to move back into the bus, boy,’ shouted the driver. ‘Good lord, getting fined is the last thing we need this morning.’

As soon as the driver stopped speaking, the man felt himself being pushed by many hands and a struggle began.

‘Brothers, please, move all the way in, God bless…’

One man punched his neighbour, the person next to him stamped on another one’s foot, and a tall man was hunkered down so much it looked as if he were praying.

‘Guys, open the window… it’s hot, and meningitis is going around!’ someone yelled.

Finally the bus arrived at the station. He pried himself from the crowd and sped off towards the office. Only when he arrived did he realise that the bus door had snagged his shirt. He tore off the flap of fabric and kept walking in his ripped shirt.

He went over it in his mind. No one will notice the tear, he convinced himself. He would try to stand so that no one could see it, and would buy a new shirt in a few days. He was a different man than he’d been yesterday when he was unemployed.

He entered the office owned by a certain businessman. (He was one of those men who appeared on the scene quite suddenly: rich, with an unknown past. All anyone knew was that he was a businessman. Since when, how? No one knew).

But… why should he care? It was none of his business, what mattered to him was this job, everything else was unimportant. He would work hard, prove his skills, and move up in life. Maybe this job would even open up other doors among the business elite.

The water would be turned back on, he wouldn’t need to do without the things on his ‘marginal list’ – he’d have everything on the list every single month. He would buy a new bathroom door, install it himself, and repair the floor. He would fix the warped front door soon, too. They wouldn’t need to skimp on sugar in their tea any more, even if it was healthier, and he would… he would… he would… He let himself sink into daydreams.

He reached the businessman’s office on the second floor, and gazed at the beautiful door, solid and well-made. It must be from a factory that makes doors and windows and other things, or maybe it’s imported, he thought to himself. At any rate, it definitely hadn’t come from a workshop in the nearby industrial zone.

A sleek, elegant plaque was a fixed up high, engraved with the word: DIRECTOR.

He felt the door, how cold it was, and took a deep breath. He grasped the handle and said to himself: I’ve done it; at last I’ve made it into the world.

But… What was wrong with it?! Why wouldn’t it open? Was it warped like his front door? Or off its hinges like his bathroom door? Did it snatch clothing like the bus door?

He turned the handle a few times, knocked, knocked again, and then again, with no response.

An office boy passed by.

‘Is the director in?’ he asked the boy.

‘You want the boss?’

‘Of course I do, why else d’you think I asked?’ he snapped.

‘Are you Amr Ahmed?’

‘Yes that’s me, in flesh and blood.’

‘Sorry, the boss said that when you arrived, to tell you that the position was offered to someone else, and he’d taken it.’

‘What! What are you talking about?’

‘Honest, that’s what happened.’

Injustice… anger… rebellion. He banged on the door and tried to force it open… and the hole in his shirt ripped further. What would happen to his children? He’d put all his hopes on this job, he deserved it, he was qualified, why had it been given to someone else? Why?!

He wouldn’t leave without getting an answer to his questions, without knowing the reason. He thought about his situation, his house, his ‘marginal list’, his brothers who trickled support to him, his warped front door, the propped-up bathroom door.

Exhausted by everything he had been through, and desperately tired of thinking about tomorrow, he threw himself to the ground before the director’s door and cried.

He cried feverishly, in defeat, out of a sense of injustice, and he lay there, intermittently lifting his gaze, wishing for it to open or for someone to look out. His wait stretched on, and the door stayed impassively shut.

–Translated from the Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette

__________________________________

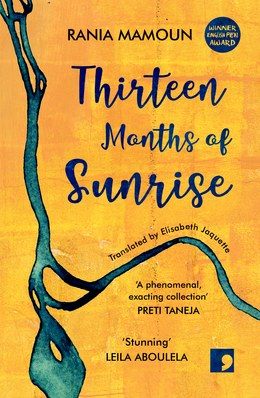

“Doors,” excerpted from Thirteen Months of Sunrise by Rania Mamoun. Used with permission of Comma Press. Translation copyright © 2019 by Elisabeth Jaquette.