Don't You Dare Call Me a Beatnik

Tosh Berman on His Dad, Wallace, and the Postwar California Art Scene

Compared with the shack in Beverly Glen, our residence in San Francisco, at 707 Scott Street, appeared to be a mansion. We had the bottom floor and various interesting people rented the upstairs. My parents became the managers of the residence and were responsible for collecting the rent and taking care of the premises. I have no real recollection being upstairs at all, mostly due to my fear of staircases. At least we had our bathroom on the first floor. I believe there was a bathroom upstairs as well, and the other tenants must have shared it.

Louise Herms lived upstairs, before she married George Herms. I found her to be very comforting, perfect even. The poet John Wieners lived on the second floor as well. There he wrote what’s perhaps the best known of his published journals, The Journal of John Wieners Is to Be Called 707 Scott Street for Billie Holiday 1959 (1996), usually referred to as 707 Scott Street. In the book, my dad figures as “Wally,” a character that wanders into the poems and leaves silently. It’s a remarkable document of that time in San Francisco, as well as a magnificent book of poetry, which, of course, I read when I was an adult.

I had a friend on the block on Scott Street who lived in a big house with a Christmas tree that was up all year round. On a daily basis, we played at the park across the street from our homes. There was no father figure in his household. Most of the kids I met had a set of parents, so when I was four or five, I was struck by the oddness that not everyone had two parents. I never asked my friend why he didn’t have a father. Even then, I was conscious of the fact that I should not ask such questions of a person unless they brought the subject up.

My parents took me everywhere. If there were a gallery opening, I would go. Sometimes, but rarely, they had a babysitter for me. The babysitters that I remember were Leslie Caron, the actress, and John Reed, the artist. The producers of the film The Subterraneans (1960), based on Jack Kerouac’s 1958 novel, wanted my parents to appear in a club setting, so they demanded a babysitter for me. Why Leslie Caron, the lead actress in the film, had to be my babysitter is beyond me.

John Reed was a rather delightful person. I haven’t the slightest idea where he came from, but I knew even then he was an artist. My parents liked him very much. He seemed to be very much of a jazzer in aesthetic and in life. I presume he enjoyed a drink or two, or many. I remember that he smelled like beer, and compared to my parents’ other friends, he was the most boho of the set. He always had a beard and wore a cap. I remember a few times when he took off his hat, his hair was all scrunched down and sweaty. He liked to laugh, and had a lazy chuckle. He seems to me to have been a beautiful soul with a hard life. His artwork was much admired by my dad, but I don’t think he ever had a show when he was alive.

He was also quite close to Walter Hopps; in fact, he used to live in Walter’s Pasadena house when Walter was in some other part of the world. Redheaded, with a red beard and freckles, he would have looked like a teen character from a situation comedy if he didn’t drink and shaved his beard. My family lost contact with him, especially after my father’s death. The last I heard of John, his body was found in the bushes by a freeway entrance.

I think I was meant to be loved from a distance. This had to do with the fact that I’m an only child. There is something catlike in that; you want someone to come up and pet you, but not hang out too much afterward.

I started reading around this time, mostly comic books. I was drawn to the illustrations, the inking, and even the smell of the comic book itself. At the time, I didn’t have a collection. But I remember my attraction to the medium was immediate. Popeye was a favorite, and I think I understood the narrative of Popeye and Bluto fighting over Olive Oyl. That triangle is part of my DNA, and I later often found myself sucked into the world of a girl and another guy. I grew out of that type of thinking or feeling in my very late twenties, but romance or yearning for attention was of great importance to me. But not in the sense that I needed someone at all times—God, no—but I think I was meant to be loved from a distance. This had to do with the fact that I’m an only child. There is something catlike in that; you want someone to come up and pet you, but not hang out too much afterward. I much prefer objects: the vinyl LP, for instance.

The first time I became aware of a vinyl LP was in San Francisco in our house on Scott Street. The album was Lotte Lenya Sings Berlin Theatre Songs by Kurt Weill (1958). It was an LP I couldn’t have escaped from even if I wanted to. Not only was it played on a constant basis in our household, but my German grandmother, Martha, also owned a copy, so when I visited her, I heard it there too. It’s a fantastic album on many levels. The songs by Lenya’s husband Weill and Bertolt Brecht are brilliant. The melodies steeped into my childhood like Peter Lorre’s voice calling out to a child in the Fritz Lang film M (1931).

Also, one of the first TV shows that I can remember was The Ernie Kovacs Show (1961-62). The program used Lotte Lenya music for its theme song, which was weird enough because that show was such an odd one for a small child to watch. Even as a teenager, I couldn’t escape: The Doors recorded “Alabama Song” (1966) and later David Bowie did a version (1980) as well. I can’t ignore the three recordings of that song. It is not about love or hate. The melody and the song are stamped on my personality.

With that in mind, it’s probably not so strange that I was raised with an image of Jean Cocteau always somewhere around the house. Cocteau was a poet, and he made poetic novels, poetic drawings, poetic art, and of course, poetic cinema. Cocteau’s definition of cinema was “poetry written on light,” which is, in theory, an excellent explanation of movies. As I mentioned before, Wallace never talked about why he liked an individual artist or art movement, but he often showed his affection by putting the artist’s image up on the studio wall, or wherever he did his artwork. The house on Scott Street had homages to the great on its walls. Someone like Cocteau made such an impression on Wallace, I think, not only due to his skills as an artist and filmmaker but also for the way he transformed his world into an artistic landscape. Cocteau’s taste reshaped his world as his personal platform. Wallace was attracted to this artist who conveyed his signature with not only poetry, but also with films, prose, drawings, and his own outsized personality.

At the time, Cocteau’s poetry was published here and there in English. My dad published one of the poems and a drawing in Semina, but Cocteau’s films made the deepest impression on Wallace and his circle during the early 1950s. A family friend and filmmaker from the Bay Area, Lawrence Jordan, owned a 16mm print of Cocteau’s Orpheus (1949). He had an incredible collection of 16mm film prints, and he would treat us to a movie after dinner. I remember I was very fond of Lawrence’s little handmade books of stills from his favorite films. Each book was focused on one film. He made one of Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible (1944), as well as Buster Keaton’s The General (1926), among others. I presume he took photographs of the movie screen.

These private showings were a real treat for me as a kid, not only for the exposure to such remarkable films as a child, but also for the seriousness of the proceedings, the sense that what we saw on the blank white wall was something incredible. Lawrence would never show anything less than fantastic. Even with the films I didn’t pick up on, owning to my tender age, I had a delightful time sleeping in front of the images flickering on the wall. The comfort of being in a dark room with my parents and their good friend made me sleepy, and that feeling has stayed with me forever. I remember watching a variety of films over at his house, but without a doubt, dinner was always spaghetti. So to this day, when I think of Orpheus or The General, I immediately think of spaghetti with tomato sauce.

San Francisco life, though fabulous for me, became difficult for Wallace, due to the beatnik culture that sprang up during the late 1950s. Always a sensitive soul who felt the vibe of his times, he was not comfortable living in the city, especially a city well known to tourists for beatnik activity. He loathed—to the very core of his being—to see a bus full of tourists stop by the Coexistence Bagel Shop and call attention to him as a beatnik. With the success of his great novel On the Road (1957), Kerouac inadvertently created a culture of people who were fascinated and alarmed by the beats. They became a joke for mainstream culture, with a TV show, The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis (1959-63), having a beatnik as one of the main characters. This funny figure—Maynard G. Krebs, played by Bob Denver of later Gilligan’s Island (1964-67) fame—became the iconic representation of what a beatnik was supposed to be at the time. Thus, anyone who wore a plain sweatshirt, sandals, and canvas pants was part of the beatnik conspiracy. Which may have been true in a cultural sense, but the beats were too unorganized of a group to overtake the youth of the Free World.

Wallace never talked about why he liked an individual artist or art movement, but he often showed his affection by putting the artist’s image up on the studio wall, or wherever he did his artwork.

When it began covering the beatnik phenomenon, the mainstream press invaded the beats’ personal space, and such space was crucial to a countercultural figure like my dad. All of a sudden his favorite hangout was overrun by tourists who wanted a look at a real “beatnik.” San Francisco became a magnet, meanwhile, for kids who wanted to join the beatnik revolution, as well as for reporters, who commented on, made demands of, and then took the piss out of a group of people who were uncomfortable in the media glare in the first place. Kerouac, for example, had a tough time going from beat writer to very famous person. It didn’t gel with his sense of culture, nor did he want to be spotlighted in such a way.

Allen Ginsberg, on the other hand, was a natural for the media. He was extremely articulate, and he was comfortable with the press and how it worked. But to my dad or someone like Kerouac, fame was a depressing process. By no means did Wallace have “Jack Kerouac” fame, but even a touch of it drove him batty. Wallace in a sense aspired to be invisible. He didn’t want to destroy mainstream culture, but he preferred to live in its margins. My dad refused to conform his particular taste or art to another’s standard, and he needed distance to work, to view, and to comment, in his way, on a world that he was both part of and alien to.

The New York Post sent a journalist by the name of Al Aronowitz to San Francisco to write a series of articles on the Beat Generation. More likely, his assignment was to expose the inner workings of a beatnik and his or hers world. Aronowitz did his research well, for he had already interviewed Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassidy, and, of course, Allen Ginsberg. Wallace, for some odd and now forgotten reason, agreed to be interviewed for the Post, but immediately regretted it. The interview took place that afternoon, and by the evening Wallace had arranged to get his friend Artie Richard to help him get the tape back so they could destroy it. They found Aronowitz in his motel room with the audio tape. There and then, my dad destroyed the tape in front of Aronowitz. The thing is, Wallace also destroyed the interview with Kerouac and Cassidy, which was also on the tape. This, one would think, exterminate the relationship between these two men. But Wallace and Al became friends, and later, in the 1960s, Aronowitz became famous for introducing Bob Dylan to the Beatles, as well as turning on the Fab Four to marijuana.

At the same time there was a growing drug problem on Scott Street. Speed was the narcotic of choice for the upstairs residents, which would have been perfectly OK if it hadn’t attracted undercover narcotic officers to the household. My father, being naturally paranoid, was alarmed when a stranger came to the house—especially if he were a friend of John Wieners. My dad was convinced John only picked up men who were undercover cops. Due to this fear and the depressing drug scene on the premises, Wallace decided to move the family to the idyllic community of Larkspur, north of San Francisco.

__________________________________

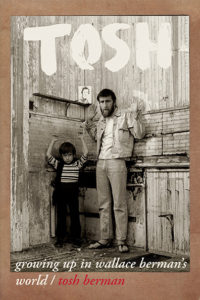

From Tosh: Growing Up in Wallace Berman’s World. Used with the permission of City Lights Publishers. Copyright © 2019 by Tosh Berman.

Tosh Berman

Tosh Berman is a writer, poet, and publisher of TamTam Books.