Documenting a Legendary Publisher's Final Project

Uncovering the Story of Barney Rosset Through Friends, Family, and a Shaman

Too few today are aware of what we owe Barney Rosset, whose legendary censorship battles smashed sexual taboos and blew open mid-century American culture. His Grove Press and its in-house Evergreen Review introduced millions of young intellectuals to progressive currents in literature, theater, film, and revolutionary politics, unleashing the 60s counterculture.

In an era when the Postmaster General was empowered by Congress to seize any material he deemed obscene, Barney was a rebel with a cause: a relentless crusade to break the back of what he saw as over-reaching government authority. Defying censors, he published the most notorious banned books of the day: D.H. Lawrence’s racy Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Henry Miller’s steamy Tropic of Cancer, William Burrough’s drug-drenched Naked Lunch. As he hoped, they were banned and seized by the government. Game on.

It took him three years of costly municipal and Supreme Court battles and near bankruptcy, but he won the right to freely publish, without constraint or interference. In a landmark First Amendment decision, government censorship was declared unconstitutional. Writers, readers, filmmakers, and comedians rejoiced. But no one rejoiced more than Barney, who went on to publish writers so radical the CIA and FBI surveilled him constantly. Among his “rads”: Beckett, Kerouac, Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, Pinter, Mamet, Selby, Sontag, Stoppard, Genet, the Marquis de Sade, Malcolm X, and Che Guevera.

I’d learned early on as a teenager that any book with Grove Press on its spine was an instant window into everything my buttoned-up parents were determined to keep me from knowing, but I didn’t meet the man behind the books until much later in life. In 2003, I went to Barney Rosset’s East Village loft with the filmmakers Al Maysles and Ed Howard to discuss making a documentary of his life. I was immediately seduced; listening to Barney was like taking a graduate seminar on mid-twentieth century literature and radical politics. He was an irresistible raconteur, a Zelig—it seemed that he’d been everywhere and knew everyone.

Although we didn’t end up making that documentary, I developed a friendship with Barney and his wife Astrid. Though I stayed in touch, I stopped going down to the loft. And then Barney died. In 2013, I went to visit Astrid and was shocked to see a surreal sculptural mural blazing across one long wall like a neon sign. In the three years I’d been away, Barney had begun something entirely unexpected.

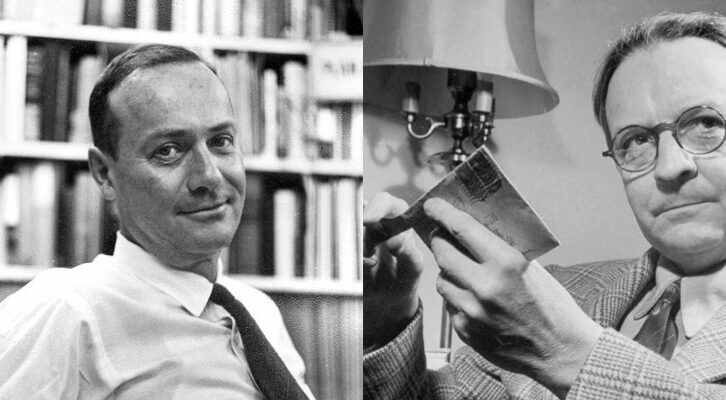

Astrid Meyers-Rosset and Barney’s wall

Astrid Meyers-Rosset and Barney’s wall

According to Astrid, Barney’s first wife, the painter Joan Mitchell, had come to him in a dream and instructed him to paint. So one morning, he removed the paintings and books from a 12′ x 22′ wall and started, sending Astrid off for acrylic paints. He began transforming Styrofoam packaging into fantastic dioramas and Velcroed them to the wall. He would roam around the loft searching for things he could embed: a Zapatista keychain, a Korean suicide knife, Day of the Dead dolls, the onyx cufflinks he’d worn to Kenzaburo Oe’s Nobel ceremony. Astrid said the local paint store knew her so well that they brought out jars of spackle as soon as she walked in.

At this time, Barney was 86 years old. Over the next three years he painted his wall mural obsessively, reworking it constantly, sleeping rarely. Friends came and went, bringing him more material. When he became too frail to climb a stepladder, he fashioned a brush out of a pool cue to reach the corners. He’d painted until just a few days before his death.

Now, Astrid said, the building had been put up for sale, and the landlord had told her she would have to move. She and Barney had been renters since moving into building in the early ‘90’s after Barney, in financial duress, had sold Grove Press, his East Hampton estate, and his Central Park South apartment. I asked what would happen to the mural. “Well,” Astrid said, “when the building is sold it will be destroyed.”

That’s when I decided a film had to be made to preserve the wall. Over the next year, whenever we found the money, we filmed Barney’s friends and family and numerous denizens of the East Village, asking them to help us interpret the wall. No one could figure it out. Why would a famous publisher and editor not include a single word? Was the wall a sort of memoir? A hallucination? Were the embedded symbols and dioramas clues? What was Barney trying to say, if anything? Was the wall simply a distraction from the thought of impending death?

Word got out and curiosity built. We filmed the reactions of two painters, an art critic, one musician, three writers, a biographer, a museum curator, three filmmakers, an underground performance artist, a tech executive, two editors, two publishers, an Iraq war veteran, an animal behaviorist, two gallerists, an architect, and one shaman. By the time the building was sold, we had accumulated ninety hours of footage, of fascinating people who had been inspired by Barney, including a Swedish director who put on a production of Waiting for Godot in San Quentin with an all-inmate cast, a legendary jazz musician’s artist son, a neurologist who explained the science of memory, a Bangkok expat writer of sexy detective novels, a young novelist who helped found Occupy Wall Street, and a shaman who channeled Barney’s spirit.

Each of them had a separate story to tell. Through their recollections, we began to trace the sources of Barney’s life-long rebellion against authority, whether it was government censorship, conventional morality, or—as time ran out—death itself. Barney had splattered his memories onto this huge wall. Every vignette was a portal. Our film became the story of Barney’s wall, and Barney’s wall is the story of Barney. It is, as a cast member says in the film, a geography of memory.

![]()

Barney’s Wall (teaser Clips) from Barney’s Wall the film on Vimeo.

Sandy Gotham Meehan

Sandy Gotham Meehan is Creative Director of FoxHog Productions and Producer/Director/Writer of Barney's Wall. Her most recent film, James Salter: A Sport and a Pastime, premiered at the Hamptons International Film Festival. Sandy is a board member of The Paris Review and of Lapham's Quarterly, and is Trustee Emeritus of The Checkerboard Film Foundation. Sandy holds a BA and MA from Stanford University in English Literature. She provides consulting expertise on narrative structure to independent filmmakers and is an expert on Kickstarter campaign development.