Discovering The Power of Books During the Syrian Revolution

Delphine Minoui on Reading as Refuge

At first Ahmad is a distant voice coming through my computer speakers. A fragile whisper from a hidden basement. When I first make contact with him on Skype, on October 15, 2015, he hasn’t left Daraya in nearly three years. Located fewer than five miles from Damascus, his town is a sarcophagus, surrounded and starved by the regime. He is one of 12,000 survivors. In the beginning, I struggle to understand what he is saying. He mumbles, timid but keyed up, his words broken by the omnipresent crackling of explosions. Between detonations, I try to focus on his face. He appears on my computer screen, then disappears, at the mercy of an internet connection patched together from small satellite dishes smuggled from abroad in the early days of the revolution.

His image stretches and deforms like a Picasso portrait: round cheeks slant at an angle under black-rimmed glasses before breaking into a million cubic pieces and fading behind a thick black curtain. When the pixels come back together, I listen carefully and try to read his lips, chewing on my pencil.

He introduces himself. Ahmad, 23 years old, born in Daraya, one of eight children in his family. Before the revolution, he studied civil engineering at Damascus University. Before the revolution, he liked soccer, movies, and being around plants in his family’s nursery. Before the revolution, he dreamed of becoming a journalist. His father quickly dissuaded him from the idea, having himself spent twelve months in prison for a simple remark whispered to a friend. “Insult to power,” the court had ruled. That was 2003, when Ahmad was eleven. A somber memory that had burrowed deep inside him.

Then the revolution. When Syria rouses in March 2011, Ahmad is 19, a rebellious age. His father, still traumatized from jail, forbids him to go into the streets. Ahmad misses the first protest held in Daraya, but sneaks into the second one. He joins the crowd, chanting at the top of his lungs: “One, one, one, the Syrian people are one.” In his chest, inside this budding revolutionary, something rips, like a sheet of paper. His first sensation of freedom.

Weeks, then months go by. The protests are unending, too. Bashar al-Assad’s voice shouts menacingly from transistor radios. “We will win. We will not yield. We will eliminate the dissenters.” Regime forces shoot into the crowd. The first bullets whistle, but Ahmad and his friends chant even louder—“Freedom! Freedom!”—as other resisters take up weapons to protect themselves. Unable to imprison them all, Syria’s president decides to put their town under lockdown. It’s November 8, 2012. Like many others, Ahmad’s family pack their suitcases and escape to a neighboring town. They beg him to follow. He refuses—this is his revolution, his generation’s revolution. Ahmad gets hold of a video camera and finally realizes his childhood dream: he will expose the truth. He joins the media center run by the new local council. In the daytime, he roams the devastated streets of Daraya. He films houses ripped apart, hospitals overflowing with the injured, burials for the victims, traces of a war invisible and inaccessible to foreign media. At night, he uploads his videos to the internet. One year of paralyzing violence goes by, full of hope and uncertainty.

The first bullets whistle, but Ahmad and his friends chant even louder—“Freedom! Freedom!”—as other resisters take up weapons to protect themselves.

One day in late 2013, Ahmad’s friends call him—they need some help. They found books that they want to rescue in the ruins of an obliterated house.

“Books?” he repeats in surprise.

The idea strikes him as ludicrous. It’s the middle of a war. What’s the point of saving books when you can’t even save lives? He’d never been a big reader. For him, books smack of lies and propaganda. For him, books recall the portrait of Assad and his long giraffe neck that mocked him from his schoolbooks. After a moment of hesitation, he follows his friends through a gouged-out wall. An explosion has ripped off the house’s front door. The disfigured building belongs to a school director who fled the city and left everything behind. Ahmad cautiously feels his way to the living room, illuminated by a single sliver of sunlight. The wood floor is carpeted with books, scattered amid the debris. With one slow movement, he kneels to the ground and picks one at random. His nails flick against the dust-blackened cover, as if against the strings of a musical instrument. The title is in English, something about self-awareness, a psychology book, no doubt. Ahmad turns to the first page, deciphers the few words he recognizes. It turns out the subject doesn’t matter. He’s trembling. His insides turn to jelly. An unsettling sensation that comes with opening the door to knowledge. With escaping, for a second, the routine of war. With saving a little piece, however tiny, of the town’s archives. Slipping through these pages as if fleeing into the unknown.

Ahmad takes his time standing up, the book against his chest. His entire body is shaking.

“The same sensation of freedom I felt at my first protest,” he whispers through the computer screen.

Ahmad cuts off, his face once again a patchwork of pixels. A detonation has interrupted the internet connection. I stare at the screen. I think I hear a sigh. He takes a big breath and continues his story, giving an inventory of the other books found in the rubble that day: Arabic and international literature, philosophy, theology, science. A sea of information in arm’s reach.

“But we had to hurry,” he continues. “Planes were rumbling outside. We moved fast, dug up the books, and filled the bed of a pickup to the brim.”

In subsequent days, the collection effort continues in the ruins of abandoned houses, destroyed offices, and disintegrating mosques. Ahmad quickly develops a taste for it. With each new hunt for books, he savors the immense pleasure of unearthing abandoned pages, bringing back to the world life buried in wreckage. They excavate with their bare hands, sometimes with shovels. In all, they are forty or so volunteers—activists, students, rebels—always at the ready, waiting for the planes to go silent so they can dig in the rubble. They salvage 6,000 books in one week. One month later, the collection reaches 15,000. The books are short, long, dented, dog-eared, damaged; some are rare and highly sought-after. They have to find someplace to store them. Protect them. Preserve this small crumb of Syria’s heritage before it all goes up in smoke. By general agreement, a plan for a public library takes shape. Daraya never had one under Assad. So this will be the first. “The symbol of a city that won’t bow down—a place where we’re constructing something even as everything else collapses around us,” adds Ahmad. He stops, pensive, before uttering a sentence I will never forget: “Our revolution was meant to build, not destroy.”

He’d never been a big reader. For him, books smack of lies and propaganda. For him, books recall the portrait of Assad and his long giraffe neck that mocked him from his schoolbooks.

Fearing reprisals from the regime, the organizers decide this library would be kept in the greatest of secrecy. It would have neither name nor sign. It would be an underground space, protected from radar and shells, where avid and novice readers alike could gather. Reading as refuge. A page opening to the world when every door is locked. After scouring the city, Ahmad and his friends uncover the basement of an abandoned building at the border of the front line, not far from the snipers, but largely spared rocket fire. Its inhabitants are gone. The volunteers hurriedly construct wooden shelves. They find paint to freshen the dusty walls. They reassemble two or three couches. Outside, they pile a few sandbags in front of the windows, and they bring a generator to provide electricity. For days, the book collectors busily dust, glue, sort, index, and organize all these volumes. Now arranged by theme and in alphabetical order on overstuffed shelves, the books find a new, harmonious order.

One last detail remains to be sorted out before the library’s unveiling: making sure that every book is numbered and carries its owner’s name, meticulously written by hand on the first page.

“We’re not thieves, and certainly not looters. These books belong to the residents of Daraya. Some are dead. Others have left. Others have been arrested. We want all of them to be able to retrieve their belongings once the war is over,” insists Ahmad.

I set down my pencil, impressed by his civic-mindedness and speechless at such respect for others. For all others. These young Syrians cohabit with death night and day. Most of them have already lost everything—their homes, their friends, their parents. Amid the bedlam, they cling to books as if to life. Hoping for a better tomorrow. For a better political system. Driven by their thirst for culture, they are quietly developing an idea of what democracy should be. An idea that’s growing. That challenges both the regime’s tyranny and the brutality of Daesh, whose fighters set the library of Mosul, in Iraq, on fire in the beginning of 2015. Ahmad and his friends are true soldiers for peace.

Another explosion rips through our conversation. Unflappable, Ahmad continues his story. He tells me how on the day of the library opening the celebration was muted—no fruit juice or streamers, just a few friends gathered for the occasion. But most important, yes, most important of all, that tingling sensation prickling in his chest again, like it did during his first protest chant.

The library very quickly becomes one of the cornerstones of this isolated town. Open from 9 am to 5 pm, except on Friday, the day of rest, it welcomes an average of 25 readers per day, mainly men. In Daraya, Ahmad explains, women and children are not very visible and rarely venture outside. In general, they make do with reading the books their fathers or husbands bring home, rather than risk the barrel bombs raining from the sky.

With each new hunt for books, he savors the immense pleasure of unearthing abandoned pages, bringing back to the world life buried in wreckage.

“Last month, around six hundred fell on the town,” says Ahmad.

His friend Abu el-Ezz, codirector of the library, was a near casualty. In September 2015, he was on his way to the book cellar when one of the many barrel bombs being tossed from regime helicopters landed in front of him. These containers full of explosives and scrap metal fall randomly and are therefore particularly destructive. Abu el-Ezz was hit in the neck by pieces of shrapnel that affected his nervous system; he suffers from cramps that stab down to the small of his back. Ever since the explosion, he’s been on bed rest in a makeshift clinic.

Detonations echo. The bombings have resumed. Ahmad continues. This time, he lets me know that he needs to end our call. We don’t know it yet, but there will be many more conversations like this one. Much longer ones, in fact. In his shattered country, where virtual connections have replaced physical ones, it’s common to spend entire evenings talking on the internet. But I’m anxious to visualize this extraordinary place. To discover the color of its walls. The faces of its readers. The titles of all the books gathered there, saved from chaos.

__________________________________

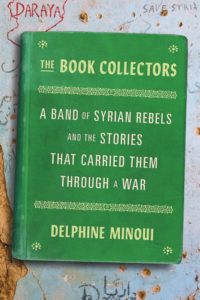

Excerpted from The Book Collectors: A Band of Syrian Rebels and the Stories That Carried Them Through a War by Delphine Minoui. Used with the permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Copyright © 2017 by Éditions du Seuil. Translation copyright © 2020 by Lara Vergnaud. All rights reserved.

Delphine Minoui

Delphine Minoui, a recipient of the Albert-Londres Prize for her reporting on Iraq and Iran, is a journalist and Middle East correspondent for Le Figaro. Born in Paris in 1974 to a French mother and an Iranian father, she now lives in Istanbul. She is the author of I'm Writing You from Tehran.