Discovering Franz Kafka’s Nearly-Lost Drawings

Andreas Kilcher on the “Grotesque, Carnivalesque” Inventions

1.

In a letter to his fiancée, Felice Bauer, on February 11–12, 1913, Kafka describes a dream that was prompted by Felice’s recollection of their first meeting in Prague in August 1912. Kafka writes that they “were closer to each other than one is when walking arm in arm” as they strolled along Prague’s Old Town Square, but then he comes up against the limits of description to capture this imagined scene: “Oh God, how difficult it is to describe on paper the invention I had made for walking not arm in arm, not attracting attention, and yet very close to you.” Just a few lines later, he has another go at it: “How on earth can I describe how we walked in my dream?” Then he finds a way: “But wait, I’ll draw it. This is arm in arm: [Drawing] But this is how we walked: [Drawing].”

This solution to his dilemma indicates a surprising priority of drawing over writing in the attempt to communicate an image—a dream image. What’s more, this surprising turn to drawing provides Kafka with an occasion to reflect on his earlier drawings, something that he does more explicitly here than anywhere else in his work:

How do you like my drawing? I was once a great draftsman, you know, but then I started to take academic drawing lessons with a bad woman painter and ruined my talent. Think of that! But wait, one of these days I’ll send you a few of my old drawings, to give you something to laugh at. These drawings gave me greater satisfaction in those days—it’s years ago—than anything else.

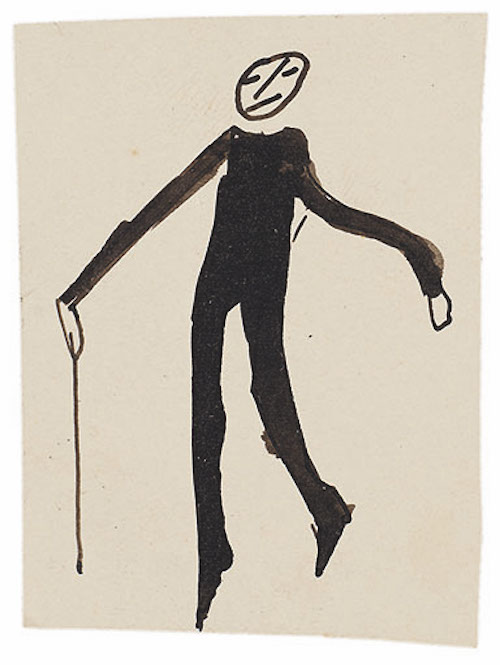

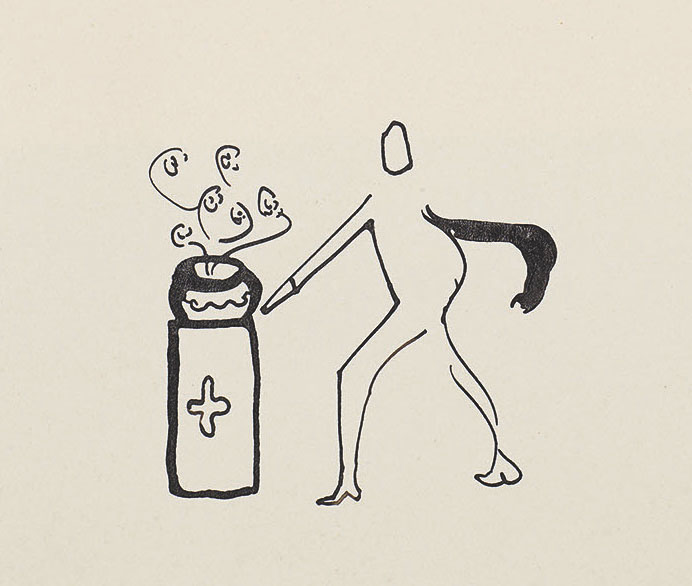

They are generally free-floating, lacking any surroundings, and in themselves they are disproportional, flat, fragile, caricatured, grotesque, carnivalesque.

Kafka’s 1913 allusion to his earlier artistic efforts—“it’s years ago”—refers to his student days with a turn of phrase that could hardly give greater weight to this occupation: Drawing “gave [him] greater satisfaction in those days . . . than anything else.” It is no longer possible to determine who the “bad woman painter” was who gave Kafka drawing lessons. However, this reference additionally clarifies how seriously Kafka practiced drawing during his time as a student from 1901 to 1906, as well as during the following year, when he was a legal trainee at the higher regional court, until the fall of 1907. Roughly 150 sketches from these years survive.

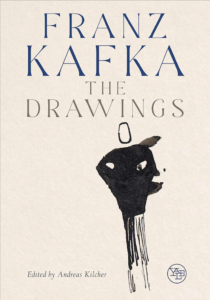

Figure cut out of the sketchbook, ca. 1901–ca. 1907; India ink on paper; 6.3 × 4.6 cm. Drawing by Franz Kafka. The Literary Estate of Max Brod, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem. Photos: Ardon Bar Hama.

Figure cut out of the sketchbook, ca. 1901–ca. 1907; India ink on paper; 6.3 × 4.6 cm. Drawing by Franz Kafka. The Literary Estate of Max Brod, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem. Photos: Ardon Bar Hama.

It is notable that Max Brod, who had met Kafka in the fall of 1902, was well aware at the time that his friend drew, but not that he wrote, as he emphasized in his Kafka biography: “I went about with Kafka for several years without knowing that he wrote.” However, Brod was positively excited to learn of Kafka’s interest in drawing, even admiring the sketches that this fellow student one year his senior shared with him from the margins of his lecture notes. These notes, printed on a hectograph machine, were “decorated with fantastical drawings in the margins. I carefully cut around these burlesque images and thus laid the foundation for my collection of Kafka’s drawings.”

Image from sketchbook, ca. 1901–ca. 1907. Drawing by Franz Kafka. The Literary Estate of Max Brod, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem. Photos: Ardon Bar Hama.

Image from sketchbook, ca. 1901–ca. 1907. Drawing by Franz Kafka. The Literary Estate of Max Brod, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem. Photos: Ardon Bar Hama.

Brod retrospectively described these circumstances in somewhat greater detail in the appendix to his book Franz Kafkas Glauben und Lehre (Franz Kafka’s Faith and Teaching, 1948). Aside from Kafka’s February 1913 letter to Felice, this is the most important historical evidence of Kafka’s early drawing. A good forty years later, Brod reports that he collected Kafka’s drawings—even earlier than his manuscripts—but also implies that there were additional drawings that Kafka destroyed:

He was even more indifferent, or perhaps better, more hostile to his drawings than he was to his literary production. Anything that I didn’t rescue was destroyed. I had him give me his “scribblings,” or I rescued them from the wastebasket—indeed, I cut a number of them from the margins of the course notes from his legal studies, those illegally reproduced “transcripts” that I always “inherited” from him (since he was one year ahead of me).

2.

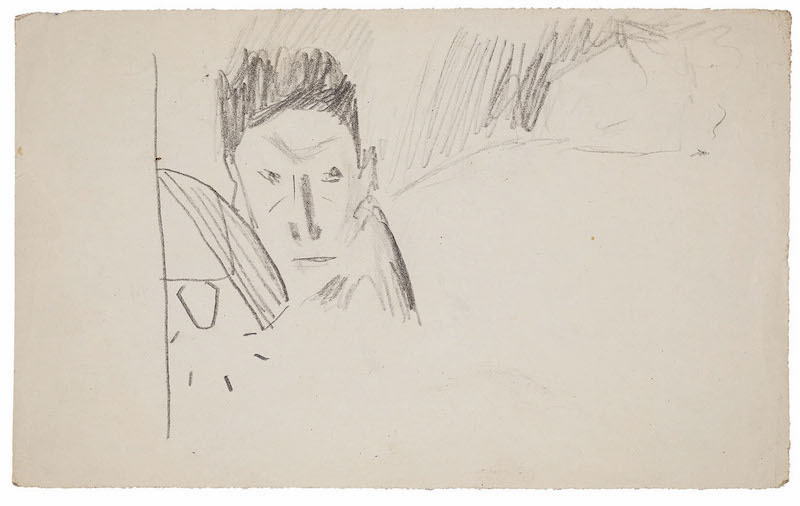

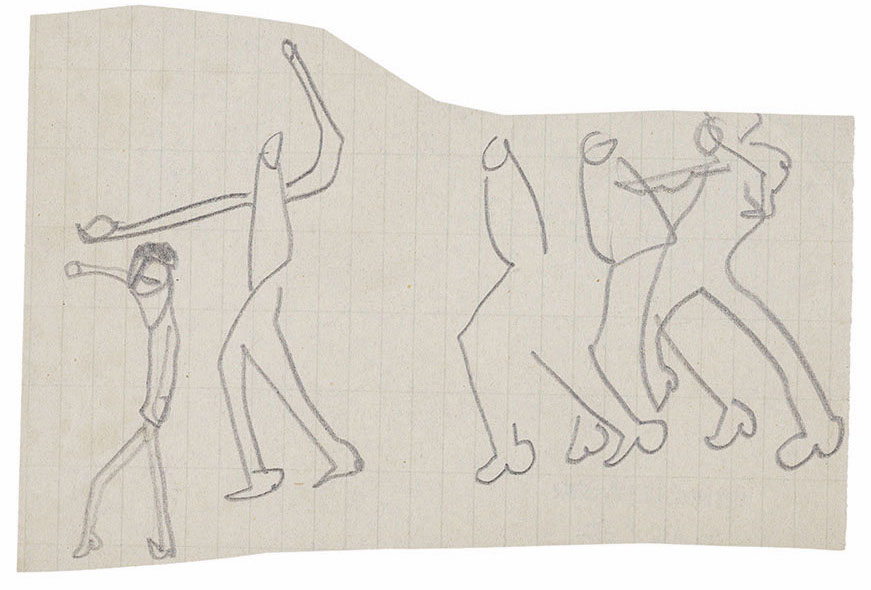

Kafka’s drawings generally suggest human faces and figures with only a few strokes. The expressions and postures are not static, but often dynamic, sometimes leaning as if in motion, usually in profile, moving from right to left. Particularly typical subjects of these drawings include fencers, horseback riders, and dancers. In addition to these dynamic individual figures, there are groups of figures that thematize “social intercourse,” to quote a term of the art historian Oscar Bie’s that Kafka attentively noted. The sketches are minimalistic from the standpoint of draftsmanship, often reduced to a few symbolic lines and strokes, with an effect that is frequently fragmentary, tentative, unfinished. Yet it would be a mistake to see them as mere drafts. What Bie emphasized in his book Die moderne Zeichenkunst (The Modern Art of Drawing, 1905), which made an impression on Kafka, can be applied to Kafka’s drawings: In the modern era, drawing has left behind its status as a mere preparatory stage for a painting and come into its own as an art form. This self-assertion of drawing, even in the quite provisional form of the sketch, was also reinforced by the new significance of printed graphic arts, according to Bie: “The art of drawing is present in the sketch as much as it is in the color print, there is no essential difference between black and color anymore, and hand-drawing is superior to reproduction only in its material value.” Kafka himself maintained that sketches, however marginal and dashed off, were a genuine art form.

Self-portrait, ca. 1905–ca. 1907 or slightly later; pencil on paper; 10.5 × 17.1 cm. Drawing by Franz Kafka. The Literary Estate of Max Brod, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem. Photos: Ardon Bar Hama.

Self-portrait, ca. 1905–ca. 1907 or slightly later; pencil on paper; 10.5 × 17.1 cm. Drawing by Franz Kafka. The Literary Estate of Max Brod, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem. Photos: Ardon Bar Hama.

This understanding of his drawings is confirmed by the subjects of Kafka’s drawings: Most of them are not fully elaborated bodies or portraits. They are not fleshed out and situated in three-dimensional space, they do not have fully developed physiques. On the contrary, they are generally free-floating, lacking any surroundings, and in themselves they are disproportional, flat, fragile, caricatured, grotesque, carnivalesque. This places Kafka’s bodies at a far remove from the classical proportions of formal “beauty.” Quite the contrary, in many cases they appear exaggerated, with certain distinguishing features strongly emphasized.

“Mob,” ca. 1901–ca. 1907; pencil on paper; 7 × 10.5 cm. Drawing by Franz Kafka. The Literary Estate of Max Brod, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem. Photos: Ardon Bar Hama.

“Mob,” ca. 1901–ca. 1907; pencil on paper; 7 × 10.5 cm. Drawing by Franz Kafka. The Literary Estate of Max Brod, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem. Photos: Ardon Bar Hama.

But these aesthetic characteristics should not be used too hastily to pigeonhole Kafka’s drawings in an art historical category; the drawings resist any attempt at a broader, more generalized classification. Just as Kafka refused to accept the role of the student in relation to the teacher, as he described in his letter to Felice, so, too, his drawings refuse to be seen as student works that follow existing models; instead, they display a striking originality that asserts itself even in its “unschooled” fashion. They should be taken seriously primarily as visual statements and artistic expressions. They are not enigmatic hieroglyphs, but rather the movements of a hand that did not follow any pattern or school, and was thus given free rein to draw.

*

Quotations are from the following sources:

Franz Kafka, Letters to Felice, ed. Erich Heller and Jürgen Born, trans. James Stern and Elisabeth Duckworth (New York: Schocken Books, 1973), page 189.

Max Brod, Franz Kafka: A Biography, trans. G. Humphreys Roberts and Richard Winston, 2nd, enlarged edition (New York: Schocken Books, 1960), page 60.

Max Brod, Streitbares Leben, 1884-1968, rev. ed. (Munich: F. A. Herbig, 1969), page 159.

Max Brod, Franz Kafkas Glauben und Lehre(Winterthur: Mondial, 1948), page 137.

Oscar Bie, Die moderne Zeichenkunst (Berlin: Bard, Marquardt, 1905), page 23.

__________________________________

Essay by Andreas Kilcher, translated by Kurt Beals. Adapted from Franz Kafka: The Drawings, edited by Andreas Kilcher with Pavel Schmidt; with essays by Judith Butler and Andreas Kilcher; translated by Kurt Beals. Published by Yale University Press in May 2022. Reproduced by permission.

Credit for lead image: Figure cut out of the sketchbook, ca. 1901–ca. 1907; India ink on paper; 5.9 × 10.9 cm. Drawing by Franz Kafka. The Literary Estate of Max Brod, National Library of Israel, Jerusalem. Photos: Ardon Bar Hama.

Andreas Kilcher

Andreas Kilcher is professor of literature and cultural studies at ETH Zurich.