Dirty Dancing Belongs in the Lesbian Rom-Com Canon

Esther Newton Makes an Important Case

Tonight in the lesbian retirement community where I spend the winter I was flipping the TV dial and happened to come across a rerun of Dirty Dancing, a 1987 film set in a Jewish Catskills resort. I loved it even more than when I first saw it. But online I learned that Jennifer Grey’s Jewish nose, which I had especially loved, had later been mutilated by her choice to have a nose job. Grey is supposed to have said that she went into plastic surgery a celebrity and came out anonymous. In other words, she chose to alter a characteristic she was born with and wound up compromising her beauty.

Although I have ideas but not certainties about why I grew up, despite relentless opposition, a mannish woman who wanted intimacy with other, mostly feminine women, I can’t remember a time when this wasn’t true. If these parts of me were not innate, like Jennifer Grey’s nose, they might as well have been. As an adolescent I wished for what might be called a “gender job”—some magic that would make me feel like other girls and everything that went with it, including heterosexuality. I felt ugly and awkward, and it was only through the affirmation of my female lovers that I gradually came to see myself as they did: a woman more masculine than feminine, with good looks and charisma who could live in her own body.

Judging by current newspaper and Facebook wedding photos, feminine-looking lesbians now sometimes marry others like themselves, and although for some reason I don’t see their wedding pictures in the New York Times, I know about quite a few masculine-masculine couples. We appreciate now that both gender and sexual orientation are not either-or propositions; that they are, rather, continuums that are much more fluid than I was led to believe as a child and young adult.

Many—probably most—lesbians are more in the middle, and many who appear to be more masculine or feminine don’t accept a “label” or look down on butches, so by no means is this the story of every lesbian, although many queer people of my age will recognize the toxic atmosphere of my youth.

*

“You are not what you want. You are what wants you back.”

–Gary Shteyngart, Little Failure

In the 1950s and 60s the partner of any butch had to be feminine and preferably identify as femme. The femme lesbian looked more feminine in dress and mannerisms, but she had antipathy toward aspects of the conventional female role, and she was attracted to butches. I presume that many of my readers, both today’s young “queer” women and others, may not know (or know that they know) any lesbian femmes, even though the identity is still evolving and vibrant. The majority of my partners have been femmes, although some did not call themselves that, and in their loving gaze I saw who I could be.

Ok, so Johnny’s a man. But we gays have had to project ourselves into heterosexual narratives.

Feminine women in mainstream media are not legible as femmes because they never get to say so and are always represented as attracted to men. Although I cannot speak for them, in trying to characterize femmes as I have known and loved them, I return to Dirty Dancing and its portrayal of a (heterosexual) femme-like attitude: Jennifer Grey’s performance of Frances “Baby” Houseman, the young Jewish heroine. From the early scene when Baby purposely spills water on a sexist jerk and walks away, you know that she is gutsy and determined. When her doctor father tries to order her around, you can see by the set of her mouth that she won’t obey. Baby pursues Johnny, a blue-collar gentile dance instructor and she keeps at it until she gets him in bed. There’s no ulterior motive. Her heart is true, and she’s not a conniving bitch. She wants him because everything about him gives her pleasure, and she’s not ashamed of it, and this is what their thrilling dancing embodies.

But there is no glossing over the fact that Johnny is a working-class guy who works as an Arthur Murray dance instructor/rent boy, while Baby is the Jewish upper-middle-class daughter of a doctor. The film acknowledges that their class differences are a powerful part of their attraction and will ultimately separate them.

OK, so Johnny’s a man. But we gays have had to project ourselves into heterosexual narratives. Working-class Johnny can’t believe that this doctor’s daughter wants him, and his attitude is not one of conquest; it is always of gratitude and tenderness. They don’t slurp open-mouthed kisses and hump in offbeat locations and positions, as in today’s conventional representations of heterosexual lust. Their masculine-feminine attraction is played out in partnered dancing and in tempo, in gestures, her hand running over his ass, the electric moment before they kiss. As Grey plays her, Baby matches Johnny’s sexy masculinity with her powerful femininity. This is definitely a queer film in the current sense, disrupting normative gender roles and heterosexuality.

The only couple I knew of who had what could be called an intellectual femme-butch relationship was in books about the lives of Alice B. Toklas and the modernist writer Gertrude Stein. Toklas willingly devoted her life to Gertrude’s comfort and success, but if this was ever the pattern of most feminine lesbians, it is no longer. As I was to discover, femmes often are not interested in domesticity and are looking for an equal relationship. They are feminine yet determined and more headstrong than submissive by temperament.

__________________________________

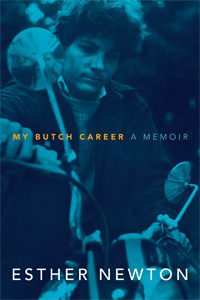

From My Butch Career: A Memoir. Used with the permission of Duke University Press. Copyright © 2018 by Esther Newton.

Esther Newton

Esther Newton is a founder of and leading scholar in LGBT studies. She has taught at Purchase College of the State University of New York, the University of Paris VII, Paris, France and the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor). She was active in Second Wave Feminism, Gay Liberation and the Lesbian/Feminist movements. Her work has been translated into French, Spanish, Hebrew, Polish and Slovak.