Did Bob Cratchit really make more than an American on minimum wage?

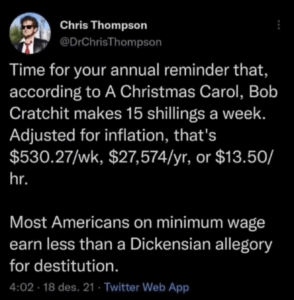

Around this time of year, I start seeing this 2021 Tweet make the rounds:

“Most Americans on minimum wage earn less than a Dickensian allegory for destitution”—it’s compelling! And it certainly feels right to someone like me, who thinks it’s embarrassing to imagine that a poor person in 19th century England might have more than a poor person in 2020s America.

But is it true? Politifact, the fact checking organization that won a Pulitzer for their reporting on the 2008 election, took on the claim in 2022 and found it to be “Half True”. They weren’t the first to question the math in the Tweet, which has been consistently challenged over the years. The writer of the original Tweet admitted that he based his math “on super-sloppy googling.” But Politifact took it to experts for evaluation.

Some experts seemed to think the claim was nearly right, including Samuel Williamson who wrote on his site MeasuringWorth.com that “Cratchit was poorly paid for the job he had, but would have had a salary with a relative earnings value of $43,000 in U.S. dollars in 2020, or $21.44 per hour, based on a 40-hour work week.” That’s much higher than the hourly minimum wage, but below the 2024 national average wages of $67,027.24 per year. This hourly calculation may be too high though, since the average worker in the Victorian era probably worked closer to 66-75 hours per week, driving the hourly wage down closer to the Tweet’s calculation.

But most of experts dismissed the Tweet as oversimplifying and attempting to extrapolate from an impossible comparison. There is no way to cleanly or accurately quantify the differences between a worker’s pay and conditions in 1840s England and 2020s America.

The basic numbers aren’t even calculable, it seems. The experts told Politifact that there isn’t even an accepted way to translate Cratchit’s weekly 15 shillings into 2020s money. “10 different people doing the calculation would get 10 different answers,” George Boyer at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations said.

Knowing this, experts use other comparative metrics like “welfare ratios” to bridge disparate contexts. These comparisons don’t back up the Tweet. Vincent Geloso, an assistant professor of economics at George Mason University, called the tweet wrong on a “great many levels,” and that “the comparison is ‘meaningless,’ arguing that Cratchit was paid well above the median Briton and that his annual income of 39 pounds was only a bit less than the U.K. average of 57 pounds in 1846.”

According to Politifact, he said that “‘well-known measure called welfare ratios, which estimate earnings divided by the cost of a basket of subsistence goods,’ show that Cratchit could buy more than six times that basket, far more than the poorest workers.”

“Cratchit was thus well above the poverty line,” Geloso concluded.

Cratchit’s profession is also relevant in thinking about his relative social and economic status. As a clerk, he wouldn’t have been considered a member of the working poor, that is, not an exact Victorian era analogue to today’s minimum wage worker.

There are a lot more interesting details from the experts Politifact spoke to, which make the compelling case that the Tweet’s claim is factually inaccurate. At best, it makes an unknowable claim. But it still catches our attention because the vibes feel right, which is unfortunately how so much of our world works these days, and the wheel of reposting remains unbroken.

To make the case for the Tweet, I’d consider it a piece of fiction based somewhat on reality. And in that reading, @DrChrisThompson has accomplished a viral microblogging equivalent to what Dickens was attempting with his novella: emotionally engaging us about the plight of the less fortunate who society and the economy have left behind.

Many people reading this Tweet probably feel like I do: it validates my anger about the state of worker’s rights and the social safety net in America. The claim is a vivid articulation of how bleak and desperate things are in the 2020s, which mimics Dickens’s inspiration for his 1843 Christmas Carol. The book was a way to channel his outrage into something that might inspire his readers to act towards the greater social good.

Thinking that Dickens’s classic “allegory for destitution” might have anything to do with an American in 2025 is rightfully infuriating. A country as wealthy as America should pay more and care more, and the fact that there’s even a half truth to the claim of Dickensian pay disparity is shameful.

James Folta

James Folta is a writer and the managing editor of Points in Case. He co-writes the weekly Newsletter of Humorous Writing. More at www.jamesfolta.com or at jfolta[at]lithub[dot]com.