Diana Arterian on Nadia Anjuman’s Life, Resistance, and Poetry

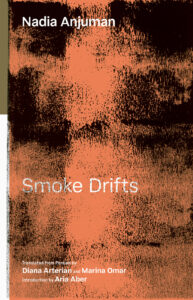

From Smoke Drifts: Selected Poems

As a teenager, desperate to learn literature, Nadia Anjuman secretly attended the Golden Needle School in her home city of Herat, Afghanistan. The women attendees hid books beneath their needlepoint, children playing in the yard to warn them of approaching Taliban morality police. If they were caught, the students could be killed as punishment. The result of Anjuman’s education is profound—reading her poems, her deep knowledge of ancient Persian poetry and contemporary writing shimmers on every page. With the fall of the Taliban, Anjuman went to the local university. She published a book of poems, catapulting her into regional fame. At the age of 24, she was set to publish another.

My edited co-translation of Anjuman’s poetry, Smoke Drifts, arrives in a moment at which my democracy is unraveling at a speed I hadn’t thought possible. Anjuman’s life and her acts of resistance throw into relief, for me, the luck of our circumstances, as bleak as they are—and all we stand to lose.

Every time I approach the fact of Anjuman’s death, I am wary. Some of this is its bald tragedy of an artist who was never able to realize her full potential. But, more prominently, I worry she will be reduced to a cliché, othered into a caricature.

If Anjuman were alive, my co-translator Marina Omar would be her contemporary. In Aria Aber’s moving introduction to Smoke Drifts, she writes, “while [Anjuman’s] poems cannot be extricated from the ruins of her circumstances, for they were born out of them, they also transcend them. Having survived, these poems serve as an anthem for the struggle for liberation that Afghan women have fought for centuries.” When recently someone asked Marina how she endured the terrible restrictions of her childhood in Kabul, she answered, with devastating bluntness, “I was suicidal.” (Marina now lives in the United States.)

Every time I approach the fact of Anjuman’s death, I am wary. Some of this is its bald tragedy of an artist who was never able to realize her full potential. But, more prominently, I worry she will be reduced to a cliché, othered into a caricature. Anjuman died by domestic violence at the age of 24.

Anjuman’s murder doesn’t make her unique—depressingly, it’s quite the opposite.

When I mention this at public events, I am quick to say her death is not unique to Afghanistan, Muslim nations, or “third-world” countries. The United States is a notably deadly place for women, with homicide as women’s leading cause of death by injury. This is not to make false equivalences—I am not pretending American girls and women are contending with the same cruelties the Taliban is exacting on women in Afghanistan. But I want to forestall any sense that the US (or what it represents) is special, different, and above such brutality.

Anjuman’s murder doesn’t make her unique—depressingly, it’s quite the opposite. The circumstances of her death link her to innumerable women across time and space. What makes Anjuman remarkable is her poetry—her ferocity and unfailing desire to continue to participate in this ancient art. How she enshrines her humanity with the poetic line.

Afghanistan is, once again, under a Taliban regime that exacts even more extreme restrictions than those of Anjuman’s childhood. School ends for girls at sixth grade. Women and girls aren’t allowed to sing, read, or speak in public.

In response, two Afghan women wearing burqas to hide their identities post videos of themselves singing poetry as an act of resistance. “Before the Taliban came to power, we had never written a single poem,” one of the women told BBC News. “This is what the Taliban did to us.” Of the poems they sing, one is by Anjuman. In our co-translation, it ends: “I am not that weak willow tree that trembles in the wind / I am an Afghan girl, and so I howl.”

*

“A Story” from Smoke Drifts

When they glimpsed my silvery fortune

they stole from me, jealously—

they kidnapped my horse

shamelessly using it to rush at me

Ugh! Curse that gang of cheats and frauds

who mocked my sincerity

They slammed every door in my face

set daggers on every window

When I opened an eye

they hammered in white-hot nails

When I bled

they turned into wolves and drank

Vein by vein they cut at my life,

thousands of blades in my one body

Why shackle my pen—

they never saw it stray

Why clip the budding smile

from the small garden of my lips

Why such hatred

Perhaps they were a nest of scorpions

After ransacking my senses

they slept, satisfied

The skies grew fitful

with the fumes of my torment

Thunder boomed

and the clouds roared

their chests burst with lightning

The pillars of the earth shook

and the clan woke up in a panic

They darted around—then froze, stunned

Their four walls collapsed

My eyes rained tears of resolve

At my hope’s dying breath,

the clouds gave it life

This is I! She who speaks

If only those thieves could see me now

__________________________________

From Smoke Drifts: Selected Poems by Nadia Anjuman. Edited by Diana Arterian. Translated by Diana Arterian and Marina Omar. New York: World Poetry Books, 2025.

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.