Diamond Forde on Memory, Mothering, and Maya Angelou

“To somebody, somewhere, this memory is history.”

On my ninth birthday, Mama took me to an independent bookstore in Atlanta, and I bought my first ever book—Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. If I close my eyes, I can still feel that moment, can see the scratched and sturdy maple shelves, the shrill of the nearby table lamps, the beautifully yellowing leaflets of paperback books. Mama winds through the labyrinth of shelves, smiling when her fingers gloss the gold spine of a good read, the same way my hand slides over Angelou’s book.

“You’ll like that one, Diamond,” Mama tells me, though she’d never read Angelou, knew her the way that I know Angelou now, as someone that I would need, someone who would confirm existence in me, my existence in the world, the kind of person that you open up to, someone who built worlds of their own, filled them with sunlight, used that light to grow other Black girls to bloom—Assata Shakur, Angela Davis, Nikki Giovanni (&&&)—Black girls raised from the plot of their soil.

I want to write my way back to them, reaching from the dirt I come from, hope that, in the doing, I raise more than myself from the muck.

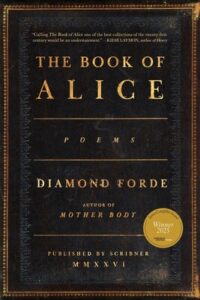

I have imagined my second book as part of that retrieval. A resurrection, The Book of Alice draws on the conventions of the King James Bible to recount my grandmother Alice’s story—her girlhood growing up in the Jim Crow South, her eventual move to New York as part of the Great Migration, and her attempts to raise a family, a legacy, herself.

Angelou was the first adult I knew to tell me the truth, to give wound to the worst harms my girl body knew—hate and hurt needling my softness, men and meanness.

Like anyone with an elegy inside them, I wrote this book because I missed my grandmother—her bird-chip laugh and callused hands, her distance—but I also wrote this book because I’m alive—am burdened with living and blessed with it, too, and the thing about living, in this world and in this moment, is that sometimes the urge to keep on living will find you, and you’ll fight for that urge, and that is when you know you want to survive. I want to survive.

And my grandmother survived. She raised eight children through any number of so-called unprecedented times, and she survived. And so did her daughters—through three hard marriages (and three hard divorces)—through poverty, hardship, racism, and loss. My grandmother survived so long she had to bury her first child. My grandmother survived until she didn’t.

And even then, she survives in me. Because she taught me how to survive. And if I wanted to keep on surviving, I realized, I needed to know my history. More than another encapsulation of the violences of white supremacy, I wanted to know my history—the series of memories, mirth and miseries, the interior and exterior moments that raised me, once lost so easily to the dirt. I wanted to know the memories that brought me here.

The memories I was losing. The memories I was made to lose.

American history is a book of fables, written through enslavement for enslavers, a falsehood made memory on our bookshelves and in our libraries, anywhere enough to supplant the truth—that our history is a mechanism of redaction wiping the lives, citizenship, and rights of Black and Indigenous peoples for centuries. How can we forget that for all that time the only evidence of Black life was monuments to our death—ship manifests, police reports, obituaries, statistics—Black life erased in the order, the law, of history. Our survival made past-tense. Our past, our lives, dehumanized into numbers. We have crossed out whole histories on our shelves for a singular narrative, swaths of people whose blood now ink our pages, whose names have been lost under the guise of time, under any title that lets us wipe our hands clean of the losing.

Every memory is precious. Every memory holding the sum of us—not me alone, but a nesting doll of memories, proof that someone in the world once mothered us, even if that mothering had to come from only ourselves.

But mothering never comes from just ourselves.

Angelou was the first adult I knew to tell me the truth, to give wound to the worst harms my girl body knew—hate and hurt needling my softness, men and meanness. Spread across the bed, lulled in the lullaby of Angelou’s lyric, I pressed my cheek against the book’s pillowed edge. Stippled hungry, I devoured each page until the last weight of orange light sank into the comforter beneath.

While I read I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, I whispered the violences of my past to Marguerite—the book’s main character—violences I would not tell my mother, violences I would not know my Mama was withholding from me, too, until it was too late to keep on hiding them, because she didn’t know how to tell her daughter, how to keep her daughter from seeing the wound the way her mother had failed to keep her from seeing.

In the years before my grandmother’s passing, my mother confronted her mother about the past. For decades, my Grandma Alice’s husband would beat her, and on the lucky days, her kids watched, waited in the wings to break them up, to shield her with the hull of their growing bodies. No doubt a struggle for my mother and all my aunts, who bore the cruelty, squashed the sight of her bowed and bloody in the compacting corners of their mind, piled up those years with newer harms, newer miseries, until some involuntary reminiscence like a bucket dipped low on the copper stench of a packed down thought got brought back up, its stink heavy as an anvil on their tongue. Then their own mother turned venom against them, the object of their wounding telling them that the shape of their wounds was never really there.

It is easier to call the time before the past, because it makes the past seem like a fixed thing, gives time order, meaning, structure—the narrative bending into our hungry palms, spilling from our damp, open mouths.

“He blacked your eye, Mom.” Mama said.

“That never happened,” Grandma snapped back. “He’d never hit me.”

“We had to pull that man off you!” The aunts chimed in. “We had to call the cops.”

Grandma turned in her wheelchair, angled her body to stare at the shadows cross-hatching and haunting the doorframe. If I close my eyes, I can still feel that moment: the salt-scratch of bile climbing up the back of my throat, Mama’s voice rising, the shuttered light slamming behind Grandma’s eyes. That’s what I remembered most about that moment: Grandma’s light bricked out, like her daughters had tripped down a tunnel she had walled off herself.

Perhaps Grandma Alice had repressed those memories, or maybe she mistook those memories as her own, worn down deep in the marrow of her, cellular and flinching, not knowing those memories had become something small enough to seed.

It is easier to call the time before the past, because it makes the past seem like a fixed thing, gives time order, meaning, structure—the narrative bending into our hungry palms, spilling from our damp, open mouths. The greatest mistake we make as Americans is believing that the wounds of our past can be forgotten, and that some seeds won’t sprout.

Sure, some pain can become so familiar, you think you’ve forgotten all about it. But the pain’s still there. The pain of our past is generational, is collective, is a series of memories thinned into thread between us, the pain we share. Even when we pretend not to. Even when we think those memories have been lost to time, to the dirt, to the mechanisms of erasure we call our past, but in any given moment there is a body, and in every body there is a moment of bodies before it, a collision of one Self against another for all eternity, body after body until the lines blur between (body&body&body&&&) teaching us how to interact with each other—how to open, how to close—each choice that has carried us here, now, something like the shape of a mother, a mother’s mother, a whole line of mothers until Eve, or anybody, who hurts like family.

In the space between you and me, reader, is Marguerite.

In the final pages of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Marguerite births a baby; her mother encourages her to sleep with the child, which scares Marguerite because she is afraid that she will roll over in her sleep, will smother the baby, so steels herself to sleeplessness, determined to remain vigilant against the threat of herself, then fails, as all mothers must do, falls asleep eventually, and in the still light of the early morning, her mother wakes her and Marguerite panics, fears she has done it, has wounded her child, then un-stiffs, observes that she has instead created a tent, crooked her child beneath her arm, scooped him into her side, and I am reading this moment, imagining myself there, too, crooked beneath the roof of Marguerite’s bicep, which looks something like my Mama’s bicep when she braids my hair, plaits it the way her Mama taught her, and perhaps this is more wish than a memory—because I remember a nesting doll of mothers in that moment, bodies cocooned around one another, in perpetuity, mother upon mother upon daughter, and if you’d like, reader, you—each of us enfolding around one other till the dark spot forming in the middle of us is us.

To somebody, somewhere, this memory is history.

__________________________________

The Book of Alice by Diamond Forde is available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon and Schuster.

Diamond Forde

Diamond Forde’s debut collection, Mother Body, was chosen by Patricia Smith as the winner of the 2019 Saturnalia Poetry Prize. She has been the recipient of the Pink Poetry Prize, the Furious Flower Poetry Prize, and CLA’s Margaret Walker Memorial Prize, and other honors. She is a Callaloo, Tin House, and Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg fellow whose work has appeared in Boston Review, Massachusetts Review, Ninth Letter, and elsewhere, and she serves as the interviews editor for Honey Literary. Diamond holds an MFA from The University of Alabama and a PhD in creative writing with concentrations in African American poetics and fat studies from Florida State University. She is an assistant professor at North Carolina State University.