Dr Logan?

Turning round to face a beautiful woman, Logan knows he should have prepared more thoroughly. A simple internet search would have furnished him with an image and given him time to mount appropriate defences. He hadn’t for a moment imagined anyone named Dr Salmon might be so generously lipped, so exquisitely cheekboned, such a confident inhabiter of eyes he is in imminent danger of falling into. Her hair is at least swept back into a bun, naturally brown (he guesses) but tinged with a deliberately exotic red tint, and a rebellious strand has broken free to frame her face. He needs a moment to reorient himself from his dowdy assumptions, a deep breath to flush out the instant fizzing in his groin.

Dr Salmon. Thank you for meeting me.

Happy to help, she says, her voice playing the melody of the words away from platitude and into an amused assessment of his surprise. Coffee, yes?

Coffee, yes. Bed, yes. Anything you ask, yes. He shakes himself as he follows her out of the building via a long corridor and seamlessly into another, he like a dog with a tick in his ear, attempting to dislodge his animal response and return to being Dr Finlay Logan.

She helps him, once they are ensconced with their cups at a table, with some verbal efficiency.

You’ve read my paper? ‘Creating God in the Human Brain’? Its full title was ‘Creating God in the Human Brain: RSMEs and Pulsed Transcranial Stimulation’.

That’s why I’m here.

He had read most of it, though when he crashed into mathematics two-thirds of the way through, he had skipped to the conclusion. The statistics he’d been forced to pick up for his degree had been hard learned and effortlessly forgotten; his brain now ceased to function if it encountered any kind of maths that involved Greek letters. The conclusion of her paper had been enough. He offers her a précis.

As I understand it you’ve used some kind of electrical stimulation of the brain to produce quasi-spiritual experiences in a number of subjects?

Her eyes drop; she seems about to have a side-conversation with the froth on her coffee.

I’m not keen on the term ‘quasi-spiritual’, she says, before re-engaging.

I’m fairly sure you used that term yourself. In the article.

She glances over to the door, pushed open by a sizeable student nodding to the beat of his headphones. Then back to Logan.

The editor added the quasi. Necessary to pass peer review. I find it rather sneery.

Sneery?

You don’t perceive it as such? Interesting. Armed with that information, do you realize I can immediately ascertain your position on the human soul? She skewers him with her eye. Tears a packet of brown sugar as though wringing the neck of a tiny paper chicken; dumps the contents into her coffee. Or rather onto, since the grains make a small glittery, taupe-coloured pile on her froth.

I’m surprised to hear a scientist even using the phrase ‘human soul’, he says. You are a scientist, aren’t you?

I’m a scientist of RSMEs, she says. It tends to come up in our work. It’s the human soul that’s under the scalpel.

Well, I’m not sure I have a position on it.

That’s the position I determined. Agnostic at the minimum. Logan has begun to think about the price of his train ticket, the hours of travelling. She is young, this Dr Salmon, and perhaps not quite as serious an academic as he had imagined.

You think you invoked actual spiritual experiences?

She laughs.

Do you know what an actual spiritual experience is, Dr. Logan?

I’ve never had one, if that’s what you’re asking.

The pile of sugar grains is sinking, beyond saving. She stirs it casually into the brew.

No, that’s not what I’m asking. Obviously if you’d had one you wouldn’t be agnostic. I mean, from a scientific perspective, how would you tell one from the other? In brain activity terms – at least with the sensitivity levels of our current equipment – I can tell you they are indistinguishable. And as far as my subjects are concerned, in experiential terms also.

So God is an illusion conjured by a pattern of firing in our brains?

She appears to be studying him. Under her gaze he feels a little like an intelligent chimpanzee, but continues, If you can show this conclusively, it’s a triumph for atheism.

That’s only one way of reading it, she says. I’m guessing you’re not up to speed with the work that goes on at the Alterman Centre.

Fill me in.

She looks ready to hand him a banana.

The public perception of neuroscience is that it’s there to back the materialist worldview. By which I mean, the idea that through science, we will prove that consciousness is a function of brain processes and that all the complexities of human thinking, behaviour and emotion can be reduced to the firing patterns of neurones. But some of the neuroscientists who have attempted to do that over the last fifty years have concluded that our model is wrong. If you believe consciousness is an evolutionary by-product, you should know there is a significant body of empirical data that argues against that orthodoxy. The Alterman Centre is not Government funded, Dr Logan. It is funded by private individuals concerned that scientific discovery be allowed to continue free from the constraints of Dawkinsism and dogma.

You speak of science as if it were a religion.

It’s the new religion, she says. Scientism. True science is something else. Genuine enquiry. No taboos.

She is watching him, he perceives, with an air of gentle amusement.

Your process. Have you tried it on atheists?

She sips her coffee before she answers.

The study was – unusually for us – dependent on Research Council funding. The focus was therefore on religious believers. A study of a pathology, from the current political perspective. A study of normal human tendency, from an anthropological one. The tendency to believe in a higher power is fundamental, Dr Logan. Still dominant in most cultures and most parts of the world.

But we have outgrown it. Evolved beyond it.

Or have we looked around at our miserable English lives, Dr Logan, and at the wider state of humanity, and simply despaired? She squeezes his arm disconcertingly and seems untroubled by the fact he’s disconcerted. Have we, in fact, discovered a way to directly connect with God through the use of electrical stimuli? Because so far I’ve not been able to ascertain any fundamental difference between what you call an actual experience and one that is induced.

Your question assumes God is real, he says.

We can’t measure God. But no one’s measured Love either. Or Compassion. Would you argue they’re not real? Of course, there are those who don’t experience love and compassion, and when questioned, will deny their existence…

You’re saying God is just a feeling? An emotion? Rather than a deity?

Humans make God ‘a deity’. I’m working on a different theory. Logan contemplates this. The hum of background conversation; the sputter of the espresso machine. He anchors himself in the comfort of normality before he continues. So your subjects, despite knowing they are taking part in a scientific experiment (he chews the words delicately, as if they are food that may contain grit)—

Believe they have experienced God, yes. Have obtained a direct connection with the Divine.

Matter of fact, as though she could, right now, reach the Divine on the telephone. And?

And what?

Logan takes a considered breath: tastes on his tongue the molecules of damp that the heat of the place has steamed from coats.

Dr Salmon, excuse me, you know little of my purpose here and have been generous enough to spare your time. As I said on the phone, my client is a religious young woman currently facing serious charges.

April Smith. It isn’t a question. I guessed, she adds. And then I googled you.

Ah, he says. Well, how much the papers are leaking I am not aware, but I must ask that anything that passes between us remains confidential.

Of course. Her unruly strand of hair suggests otherwise. I might be trustworthy and controllable, it says. And I might not.

My client, he continues, wary of uttering her name in a public place, is not speaking to anyone else but God. And if I’m to help her, to assess her and therefore help her, I need her to speak to me.

To assess her and therefore help her? Dr Salmon repeats, her mouth twisting a little as though trying to contain a live worm. Your assessment will help her, will it? You know this in advance?

It is always my intention—

He knows he sounds pompous. The woman is making him pompous. Time to reboot.

Gabrielle – may I call you Gabrielle? She nods. What I want to know is what happens to your religious subjects after they – to their minds, at least – experience God at the push of a button?

Not quite the push of the button, she says, but I understand your meaning. Under laboratory conditions.

Invoked by you, he says. After their God experience at your hand, are they – are they changed?

She gazes out, through condensation, at the main campus concourse.

Yes, very much so.

In what way?

How would you put it? At peace with themselves.

And suddenly he twigs. What it is about her, Dr Salmon, that has been needling him from the outset.

You’ve experienced it yourself. Whatever it is that you do to create – what did you call it?

She smiles.

A direct connection with the Divine.

You’ve experienced it yourself, he says, allowing the repetition to harden his suspicion into fact.

She doesn’t say yes. She doesn’t say no.

Would you not be curious? she asks. In my position? Seeing my subjects go in as normal, agitated, messed-up humans and come out – I don’t know – like all the bad stuff is erased?

Logan can’t help thinking he likes normal, agitated, messed-up humans. The idea of any part of him being erased – even what she so unscientifically calls the bad stuff – is less than appealing. Although if she could excise his grief, just his grief; if she could cauterize that without losing one atom of the love that gave birth to it, without dulling a single memory of the moments he will never have again…

No, not possible. The grief and the love are one. He puts the personal away; returns to a more professional concern.

But how can you be objective when you have experimented on yourself?

She shakes her head, but the smile doesn’t come off. You’d be surprised how objective one can be after experiencing oneself as an aspect of infinite intelligence.

She is surely toying with him; the mobility of her lips confirms her amusement. Then they straighten out, as if she told them to behave themselves. But in terms of the paper you read, you must understand that when I wrote it I hadn’t undergone the process. It was only after publication that I – she seeks out an appropriate word – succumbed. I was just too curious not to.

Embarrassed for her, he stretches for the kind of polite trope that awkward conversationalists adopt when a subject has petered out.

Have you always been religious?

She surveys him steadily.

I’m not religious now. I’m not in the slightest bit interested in religion.

But you believe you’ve experienced God?

She laughs the way a kind teacher might laugh when faced with the earnest seriousness of a five-year-old.

Believe me, Dr Logan, religion may have everything to do with God, but God has nothing to do with religion.

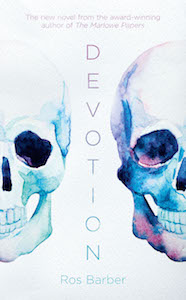

From DEVOTION. Used with permission of Oneworld Publications. Copyright © 2015 by Ros Barber.