Denise Levertov Should Be More Famous

How Do You Immortalize a Willfully Uncategorizable Poet?

“And I walked naked

from the beginning

breathing in

my life,

breathing out

poems,

arrogant in innocence.”

–from “A Cloak”

Denise Levertov is one of the best, most interesting poets of the 20th century, but her place in the firmament of poets could hardly be described as central; her work rattles around in anthologies and her name is familiar to most poetry students. But no young poets are flying her banner. Her work is not selling as well as it should. While she’s not in danger of being forgotten anytime soon, Levertov’s legacy is in question.

Emily Warn, a Seattle poet who was Levertov’s friend at the end of her life, tells me frankly, “I don’t think she’s as much a part of the literary conversation right now.” Warn finds it “interesting that Catholics have taken her up,” that Levertov’s work is popular at Catholic educational institutions like Loyola, the Jesuit law school in Chicago. But even in her adopted home of Seattle, Levertov runs the risk of retreating to that terrible dusty library aisle where forgotten poets go.

This Saturday, May 16th, is officially Denise Levertov Day in the city of Seattle. This is thanks in large part to the Catholics—specifically to the Jesuits of St. Joseph Parish, where she was an active member—who petitioned the city to create Levertov Day as the capstone to a two-week festival featuring screenings of videotaped Levertov readings, group investigations of her poetry, a graveside blessing and reading, new poems inspired by Levertov’s work, and the presentation of a new choral work based on Levertov’s poem “Making Peace.”

How many poets, even posthumously, have inspired an entire festival in their name? The Levertov Festival is an attempt to inspire a new generation to investigate her work. For a poet who’s been gone for nearly two decades, it’s another shot at immortality.

* * * *

Let’s get the Wikipedia stuff out of the way quickly.

Denise Levertov was born in England in 1923. Her father was a Hasidic Jew who converted to Christianity and became an Anglican priest. At 12 years of age, Levertov sent some of her poems to T.S. Eliot, who replied with an encouraging letter that likely cemented her self-image as a poet. (What inspired the famously sour Eliot to cast his intrinsic prickishness aside on this one occasion is a happy mystery that will forever remain unsolved.) During World War II, she remained in besieged London, working as a nurse.

After the war, Levertov fell in love with an American and moved to the U.S. with him. There, she met William Carlos Williams and associated with the postmodern Black Mountain Poets. Over the course of her career, she became known as a political poet, openly registering her disapproval of the Vietnam War and the first Gulf War in poems at a time when poets were encouraged to be apolitical. She taught poetry at Brandeis and Tufts and MIT and the University of Washington, and as The Nation’s poetry editor she published scores of women poets and anti-war poets. Levertov loved to travel, but she made her home in New York City, and then in Somerville Massachusetts, and, finally, in Seattle, where she died in December of 1997.

But these are just facts.

The truth is that Levertov never considered herself to be a British poet, or an American poet. She did not want to be known as a protest poet, or a spiritual poet. She rejected close ties with the Black Mountain Poets. She preferred to not be referred to as a feminist, though women’s issues were important to her. She was not a New York poet, or a Boston poet, or a Seattle poet. Her friends tell me she would rather not be thought of at all than to be intrinsically tied to any single school or cause or allegiance.

Over the last month, I read the Collected Poems from cover to cover. My previous experience with Levertov is likely akin to yours–I knew the name, I’d encountered her work occasionally, but I had no impression of her. She was a persistent whisper in the cacophonous history of American poetry. For the last four weeks, I’ve isolated her voice, followed it from birth to death, and familiarized myself with its peculiarities until it became as familiar as my own breath.

What follows is a love story.

* * * *

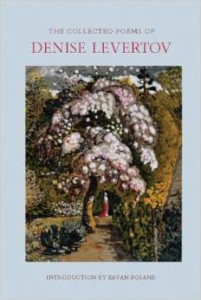

This book. You can’t hold this book without a visceral response rising up from somewhere in the core of you, as though it vibrates or hums or emanates some kind of semi-phosphorescent glow. But it’s surely not simply aesthetic appeal. It’s like falling in love across a crowded room, this book. The dust jacket is fine enough in its own way: a shiny slate blue, mostly, with just the words “THE COLLECTED POEMS OF DENISE LEVERTOV” above a Samuel Palmer painting of a woman standing underneath a luminescent tree. You’ve seen better covers, but you’ve seen worse, too.

Nor is it just the heft of it, though it could be carved from marble, it’s so dense. Over a thousand pages of poems, all helpfully arranged in chronological order by publication date. A life’s work.

And sure, it’s “immense” and “heavy” and “substantial.” But that’s all physical, and the quality that imbues this book with its air of specialness doesn’t come from a manufacturer. Just holding the Collected Poems and flipping through its blinding white pages (archival stock, you’ll notice, the kind of paper that’s made with apocalypses in mind) you start looking for adjectives to fit it. “Sacred” might skitter to the top of your consciousness, but it’s maybe too much. People tend to use “sacred” too often when they’re talking about poets, which is part of the reason why Americans treat poetry readings the way they do church—something to be avoided unless a close friend or family member guilts you into it.

And it’s not “imposing,” because before you even take a moment to acknowledge the decades of work and craft and inspiration and intellect that went into the writing of the book, your greedy fingers are already turning pages and your eyes are lapping up stanzas like they’re a lover’s face.

No, the word that really fits is “magisterial.” The Collected Poems is a regal work. Levertov isn’t an imperious poet—and we’re getting to her writing soon enough, I promise—but she is a poet who inspires you to follow, to see where she leads. She commands your attention.

* * * *

It might seem silly to worry about Levertov’s legacy in a world where the Collected Poems is in print. With its approachable density, it promises her a place of prominence on bookstore and library shelves for decades to come. And in fact, the Collected Poems is the best legacy a poet could ever ask for. It’s not a complete overview of Levertov’s life—it doesn’t contain her essays or memoirs, after all—but anyone who sits with this book, spends time with it, will discover the full breadth and depth of her work.

The problem with any chronological collection of poems is that the first poems are going to be the worst. And in fact the opening pages of the Collected Poems are the most difficult to read as a young Levertov imagines herself as another cobblestone in the winding country path known as Proper British Poetry. The poems are polite and obsessed with rhyme and meter. Levertov writes about nature in a clinical fashion, and you can see her uncertain, youthful writing struggle to assume what she imagines to be a jaded poet’s omniscience. Consider this, the opening of “Meditation and Voices”:

The mortal failure is the perfect mask,

the adamant and long desired defence.

Assiduously, like soft approaching nightmare,

we amplify the sinister pretence,

ignore the fable which we dare not fear,

turn a deaf ear to death, cover our tracks.

But you and I lack skill in prison building;

anger and love still enter by the cracks.

Let’s be clear—this is not terrible poetry, it’s just terribly uninteresting poetry, There’s nothing new here: the barrage of punctuation; the awkward framing; the wedged-in “Assiduously;” the hoary appearance of that most overhyped poetical stage player, death, who I can’t help but picture as a buffoonish, bureaucratic grim reaper straight out of a New Yorker cartoon.

Finally, 43 pages into the book comes Here and Now, Levertov’s first work after moving to America and her first published collection. The serious-minded, color-inside-the-lines poet at the beginning of the book disappears, to be replaced with a poet who doesn’t seem to give a damn about what you think. Here’s a piece of “The Earthwoman and the Waterwoman:”

The earthwoman

has oaktree arms. Her children

full of blood and milk

stamp through the woods shouting.

The waterwoman

sings gay songs in a sad voice

with her moonshine children.

Whoa. Where did this poet come from? You can’t even draw a line connecting the “sinister pretence” of the first example to the “children/full of blood and milk” in the second. As I’ve already mentioned, Levertov didn’t want to be known as an American poet, but it’s difficult to deny that moving to America and befriending American poets freed her writing from staid British formalism. From Here and Now on, the Collected Poems is shot through with electricity; the words sizzle and smoke on the page. This American transition is the first of three major transformations Levertov will make in the Collected Poems, and it is by far the most dramatic, the literary equivalent of that hokey rom com trope when the nerdy girl takes off her glasses to reveal the prom queen hiding underneath. Only instead of becoming an object of masculine and feminine sexual desire, Levertov becomes a fire-eyed goddess, a truth-teller whose emotion is stronger than anything else in the universe.

The most fascinating aspect of Levertov’s emergence from this chrysalis is that she didn’t eschew the rhythm and meter of her earlier poems. Instead, she internalized the rhythm and made it really count. Every poem dances to its own new music, rather than the boring beats that everyone else keeps recycling generation after generation. Consider the opening stanza of “Zest,” a poem that is, yes, written in all-caps:

DISPOSE YOUR ENERGIES

PRACTISE ECONOMIES

GO INDOORS, REFUSING

TO ATTEND THE EVENING LANGUORS OF SPRING

Whereas “The Earthwoman and the Waterwoman” sang soulful duets, “Zest” is death metal, relentless and intense. You half-expect it to end with an overwrought Pink Floyd-style refutation of organized society, but instead it concludes on a roof at sunset in awe of the beauty of it all: “UP/OVER THE RED DARKNESS DOLPHINS/ROLL, ROLL, AND TUMBLE, FLASHING THE/SPRAY OF A GREEN SKY.” This refusal to supply a moral or a pat conclusion is part of Levertov’s unending charm; there’s beauty in brutality and vice versa. You expect the melancholy waterwoman to be identified as preferable to the strong, lusty earthwoman, but that moment of judgment never comes.

Levertov’s poetry is confessional, in that most of it seems to be based on her own life. She frequently refers to friends and family by first names. Her poems take place wherever she is on Earth at the moment. Sometimes she reads something in the paper that inspires a poem. Warn describes Levertov’s process as being less of the write-every-day sort and more of the wait-and-see-what-happens school. “She’ll have an encounter, she’ll have a dream, she’ll read a book, she’ll go to a museum and see a painting, or she’ll have a really intense conversation with a friend,” Warn says, and a poem will follow. But Levertov is not interested in the gaudy striptease of melodrama or the fussy ugliness of score-settling. With her precision and her enthusiasm, she’s drawing you close with her confessions and as you lean in to hear those whispered truths, you realize that she’s gently turning your body until you’re both staring in the same direction.

Levertov’s poetry is confessional, in that most of it seems to be based on her own life. She frequently refers to friends and family by first names. Her poems take place wherever she is on Earth at the moment. Sometimes she reads something in the paper that inspires a poem. Warn describes Levertov’s process as being less of the write-every-day sort and more of the wait-and-see-what-happens school. “She’ll have an encounter, she’ll have a dream, she’ll read a book, she’ll go to a museum and see a painting, or she’ll have a really intense conversation with a friend,” Warn says, and a poem will follow. But Levertov is not interested in the gaudy striptease of melodrama or the fussy ugliness of score-settling. With her precision and her enthusiasm, she’s drawing you close with her confessions and as you lean in to hear those whispered truths, you realize that she’s gently turning your body until you’re both staring in the same direction.

That confessional impulse would eventually become a moral one. Levertov’s second transformation, in the 1960s, is heralded by the names that suddenly started appearing in her poems: Vietnam, Biafra, Ho Chi Minh. She refers to “photos of napalmed children” and “coarse faces grinning, painted by Bosch / on TV screen as Humphrey / gets nominated.” Having lived through the horrors of the Second World War, Levertov felt compelled to speak up about the Vietnam War. She encouraged her students to walk out of class and protest. Her righteousness was strong, but she understood that poems crafted out of rage rarely stand the test of time, so she worked to craft political poems that she believed to be as lyrical and thoughtful as all her other works.

In the end, Levertov decided to delay the shower and visit Elliott Bay Book Company with a paper bag on her head so nobody could see how greasy the road trip had left her.

This was, at the time, a controversial decision. The poet Robert Duncan, long a friend of Levertov’s family, wrote many letters trying to scare her off the path of protestation. In one, he warned Levertov and her husband that “you both stand now so definitely at the front of—not the still small inner voice of conscience that cautions us in our convictions but the other conscience that drives us to give our lives over to our convictions, the righteous Conscience—what Freudians call the Super Ego, that does not caution but sweeps outside all reservations.”

Duncan believed the peace movement was inextricable from the forces that caused the Vietnam War: “…the revolution, like Nixon, believes in inflicting peace on their own terms. I do not ask for a program of Peace; but I do protest the war waged under the banner of Peace, no matter who wages it,” he wrote. This was not an unusual position at the time.

Perhaps because the anti-war counterculture of the 1960s has been documented ad nauseum, it’s easy to forget that you could find plenty of artists and poets at that time who were interested in maintaining the status quo. Poets, especially, were loath to lose their privileged pet status in academia by causing a stir. Better to focus on trees and yearning and snow than to argue against gross injustice.

Levertov argued with Duncan and with anyone who claimed that poets should not be giving speeches at protests; her outrage was an inextricable part of her humanity, so why should she deny it? Rather than couching her language in equivocation, Levertov published a furious poem in which she infiltrated the White House to murder Henry Kissinger (with a dagger to the belly) and Richard Nixon (with a vial of napalm to the face) and Nixon’s “friends and henchmen” (with “small bombs designed / to explode at the pressure of a small child’s weight.”) She lost friends and likely tarnished her reputation.

She did not yield.

Levertov’s third transformation was the most gradual. In 1989, Levertov performed at Bumbershoot, Seattle’s annual arts festival, where a young poet named Emily Warn was assigned to escort her around Seattle and keep her entertained. Warn says Levertov had “been thinking about getting out of Somerville,” and the trip to Seattle impressed her so much that she headed back to Somerville and made the arrangements to move almost immediately.

Levertov made the cross-country trip in a U-Haul truck, and Warn and a handful of other local poets greeted her when she arrived in Seattle. On arriving, Levertov talked about the dueling impulses she felt. On the one hand, after spending a week in a moving truck, she wanted to clean herself up. But on the other hand, she had just arrived in Seattle and she wanted to visit the city’s most gorgeous literary institution: Elliott Bay Book Company, a bookstore she had learned to love over the course of many reading tours. In the end, Levertov decided to delay the shower and visit Elliott Bay Book Company with a paper bag on her head so nobody could see how greasy the road trip had left her. She chose the pilgrimage over her physical needs, a recurring theme in her later years.

At the end of her life, her poems reflected an increasing interest in spirituality. Warn downplays the religious aspect of Levertov’s work. “She liked the cultural aspect of the church,” Warn says, but “my experience with her was not so much as a Catholic but a believer.” She sees the later spirituality as a natural extension of her political works. Still, something was undeniably happening in these poems.

From the porch of her home on Lake Washington Boulevard, Levertov could see both Mount Rainier—the immense snow-capped volcano that looms to the south of Seattle, promising breathtaking views and the potential of spontaneous widespread destruction—and the enormity of Lake Washington. They both recurred in almost every poem she wrote near the end of her life. Warn notes that Levertov never named either landmark in her work; they were always “the mountain” or “the lake.” To Levertov, they seemed to stand for something larger than physical features. For Levertov, nature was not so much a challenge to enjoy (she wondered why anyone would ever go hiking, Warn remembers, calling even the thought of it “strenuous.”) as an idea to ponder, a responsibility to keep. When she wrote about the mountain, Levertov could just as easily be writing about God, and vice versa.

Levertov was very aware of the change in her work. Warn recalls that one day Levertov said she hoped that William Carlos Williams wouldn’t be disappointed in her “because she’s returned to the language of her childhood.” The poems were becoming simpler, more pared down in their language and in their scope, with occasional flourishes of uncharacteristic romanticism. In one poem, she refers to a heron on the lake as “a tall prince come down from the castle to walk / proud and awkward, in the market square.” In another, she watches a neighbor’s labrador clamber up “on hind legs to bend with his paws / the figtree’s curving branches / and reach the sweet figs with his black lips.”

This final transition saw Levertov reinvent herself again into a kind of Northwestern Basho, a taxidermist of moments. Through this pursuit of minimalism, she seemed to find answers to larger questions. Even I, an avowed atheist, can find the beauty in a poem like “Primary Wonder,” one of the last entries in the Collected Poems. In it, Levertov laments her “problems offering / their own ignored solutions” which “jostle for [her] attention… along with a host of diversions, my courtiers, wearing / their colored clothes; caps and bells.” Levertov, according to many who knew her, made friends promiscuously. She loved attending readings of all kinds, from lectures at the University of Washington to book launch parties at Elliott Bay Book Company to a plucky experimental poetry series hosted out of a dumpy vegan cafe. Her life was full of distractions, which she happily courted; she adored what she called “play” of all types. But she found time for introspection, too, as the second and final verse of the poem demonstrates:

And then

once more the quiet mystery

is present to me, the throng’s clamor

recedes: the mystery

that there is anything, anything at all,

let alone cosmos, joy memory, everything,

rather than void…

In other words, we are something, and that ain’t nothing. It’s a spiritual argument, but it’s also a demand for silence, for understanding, for humility; it’s a portrait of a woman who lived a life that was overstuffed with friendships and travel and emotion but who also managed to make enough time to write enough meticulous poetry to fill a book as huge and wondrous as the Collected Poems. She willed that book into the world from nothing, one word after another, over the course of a lifetime.

* * * *

Denise Levertov was buried at the top of a hill in Lakeview Cemetery in Seattle, in a shaded plot with a view of, as she called it, the lake. Not too far downhill from Levertov are the graves of Bruce Lee and his son, Brandon Lee. The steady stream of Enter the Dragon and The Crow fans on a celebrity-death pilgrimage will sometimes interrupt reveries at Levertov’s graveside to ask for directions. This can get a little wearying. But on the whole, if you’re looking for a place to spend forever, the site is just about perfect.

Saint Joseph’s put a small committee including Warn and Seattle poet Jan Wallace in charge of choosing a tombstone for the grave. They did an admirable job. It’s a huge black rectangle, substantial and dense, and in a pleasant literary font it reads, simply:

Denise Levertov

1923-1997

On top of the stone is a sculpture. It’s by a local sculptor named Phillip McCracken, who both Levertov and her son, Nikolai, had grown to admire; Levertov had visited his studio not long before her death. From a distance, the sculpture looks like a small granite boulder, but as you get closer, you can see the beginnings of shapes erupting from its surface; a smooth concave bit hollowed from its side, a point carved at the base. From one angle, it looks like an arrowhead; from another it’s an egg; from a third it’s a cube. It captures the moment of becoming, that boundless possibility before the shapes take hold and seize your recognition, force you to acknowledge they resemble one object or another. The sculpture is caught in that eternal instant of possibility, evading categorization and identification.

On top of the stone is a sculpture. It’s by a local sculptor named Phillip McCracken, who both Levertov and her son, Nikolai, had grown to admire; Levertov had visited his studio not long before her death. From a distance, the sculpture looks like a small granite boulder, but as you get closer, you can see the beginnings of shapes erupting from its surface; a smooth concave bit hollowed from its side, a point carved at the base. From one angle, it looks like an arrowhead; from another it’s an egg; from a third it’s a cube. It captures the moment of becoming, that boundless possibility before the shapes take hold and seize your recognition, force you to acknowledge they resemble one object or another. The sculpture is caught in that eternal instant of possibility, evading categorization and identification.

It’s called “Stone Poem,” and it’s absolutely perfect.

Paul Constant

By day, Paul Constant is a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator devoted to ideas, policies, and actions that catalyze significant social change. By night, he’s a co-founder of the Seattle Review of Books, a new book news, reviews, and interviews publication intended to reflect the reading life of the modern Seattleite.