Defiant Style: A Story of African Women, in Photographs and Fashion

Catherine E. McKinley on the Sewing Machine as a Tool of Empowerment

For African women across the continent, many of the most powerful but less remarked upon modern legacies were born of the sewing machine and the camera.

This may seem like a bit of a wild claim: to survey the late 19th and 20th centuries and elevate these two instruments of modernity above the car, above other industry, above medical innovations and the tools of agriculture, above even the machinery of electricity-making and all that it powers. But for decades after the fall of colonial regimes, beginning with Ghana’s Independence in 1957, very few of these other things reached democratically or consistently into most African lives, especially women’s. And even now they remain elusive, including consistent power or water even in the most state-of-the-art corners of metropolises, whereas the camera and the sewing machine slowly became part of the quotidian—steadfast instruments that offered a powerful means to author one’s own life.

Print Pigments, 26×25 cm (30×40) 02/07 ex

Print Pigments, 26×25 cm (30×40) 02/07 ex

This story is best told in photographs, in its own medium. A little more than 150 photographs, gathered from disparate corners. Imperfect documents. No perfect exegesis to be formed. Simply, they hold the story of two colonial machines and the unquantifiable, mostly hidden history-making of the women who were either taken up by these instruments or who took them up, altering, most noticeably, fashion and image, and with them, everything from art to politics, industry, medicine, and the local and world economies. In fact, the very course of the Colonial Project itself.

The Western industrial machinery of sewing was introduced to the African continent in the mid-to-late 1800s, soon after it was officially declared an invention and widely patented in Europe. The first sewing machines to arrive on the continent were kept at trading and bulking stations attached to colonial fortresses. These buildings often housed or had attached to them small factories that produced garments—primarily uniforms and mission wear—in addition to piece-making and the finishing of cloth, to be dispatched in a widespread and lucrative inter-African trade.

These machines were at first the sole privilege of Europeans and African royal classes. In many African cultures, it is still customary to bury the dead with possessions that represent one’s personal and social power—to serve them in their otherworld domain. A nineteenth-century reliquary, placed on the grave of a Mboma regional chief, is revealing of the social value and the hierarchies of early sewing machine culture.

For African women across the continent, many of the most powerful but less remarked upon modern legacies were born of the sewing machine and the camera.

Over time, other African elites acquired machines, and slowly they became democratized (often through missionary education), though still costly, possessions. Hand-sewing was abandoned, innovations in design quickened, and economies widened. The sewing machine became a common dowry item—as essential to the running of a household as to a woman’s economic freedom, whether she sewed herself or chose to hire the machine out to local seamstresses.

Today, vintage hand or pedal-powered machines like the iconic Black Butterfly, which resemble the Congo reliquary, are still reliable staples alongside the latest Japanese or German computerized imports.

The first photography—the daguerreotype—arrived in Egypt in 1840, soon after François Arago’s official announcement in 1839 at the French Chamber of Deputies of painter and printmaker Louis Daguerre’s invention of the technology. There are similar photo documents of North and sub-Saharan Africa taken very soon after by adventurers. But it would be almost another decade and a half before cameras would arrive in any number in the colonial trade. Once they did, unlike the sewing machine, with its early hierarchy of ownership, cameras were at once taken up by Europeans and Africans alike. Much of the early history of photography in Africa is yet uncovered, but as we map the first known studios, dated from 1853, we learn they are just as often owned by Africans as by European and Lebanese merchants, and by Black political exiles, expatriates, and returnees from the United States and other nations complicit in the transatlantic trade.

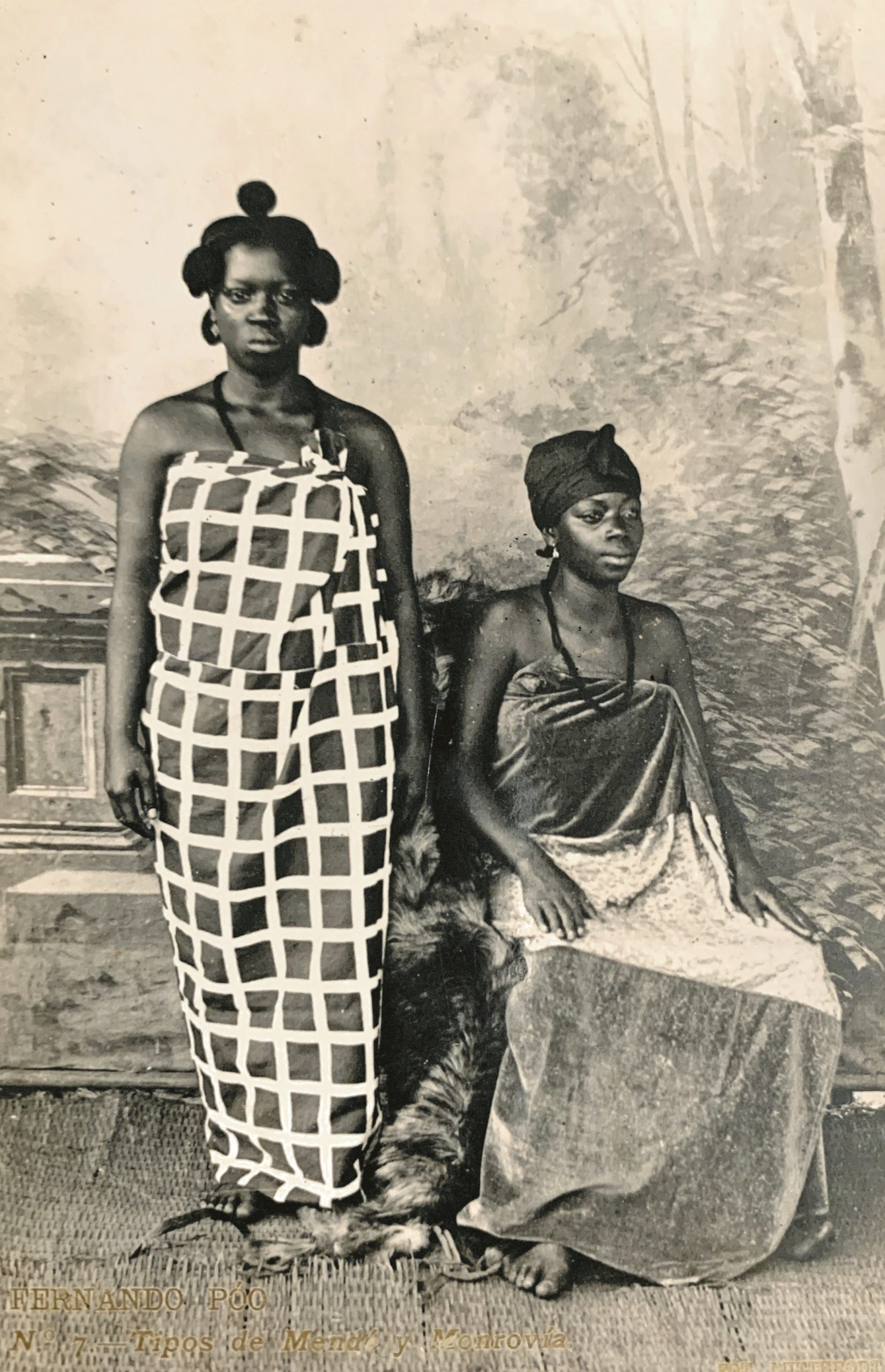

For Europe, photography was one of the most effective ways to bind the disparate and far-flung campaigns of Empire. It helped to establish a master narrative of colonial conquest and made the efforts real both to those in Europe and throughout the colonies, where imaginations and morale might falter. Photos were used by colonial governments as a powerful tool of propaganda-making, as a means of reporting, and for European fascination and popular entertainment in the form of stereographs, postcards, cartes de visite, and eventually moving pictures.

In 1869, with cameras in wider circulation, the Colonial Office in London sent instructions to governors worldwide to have all “races” in the British Empire photographed and cataloged to further “science” under the Crown. “Categorize, define, and subjugate” was the mandate. When army engineers were sent with weaponry on expeditions in an African nation’s interior, cameramen joined those missions to document infrastructure, missionary projects, and pacification campaigns, as well as to map and survey the land and document who inhabited it. From this practice, the formalization of racist typologies and state-sponsored pseudoscience took deeper root—both of which would have great bearing on twentieth-century societies in Africa and the West, particularly in how women’s lives were administered by the State.

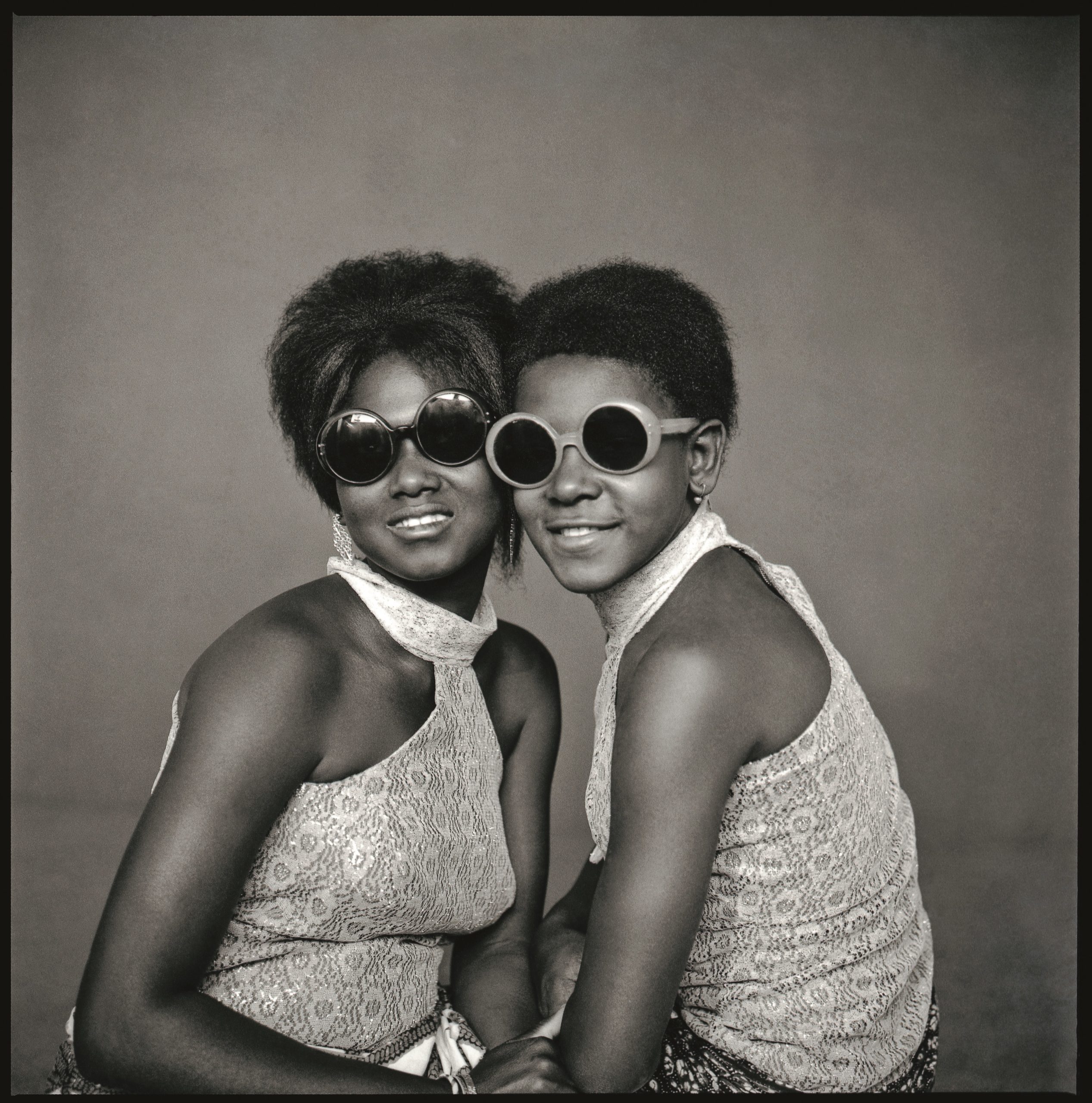

African entrepreneurs often learned photography from individual studio owners, and as colonial government trainees who were eventually employed to work alongside European civil servants. Many eventually opened independent studios, including itinerant ones, crossing national borders and stationing themselves for periods as state documentarians and photographers for a clientele of African elites. In studio spaces and the homes of their clientele they produced images that were often artful—if not masterful—for the intimacies they captured and the display of bourgeois fashions. At the same time, non-Africans catered to more rarified niches of European, African, Creole, and mixed-race clientele, while also creating the endless mire of “everyday” exotica: the mammy figures and “tribal” curiosities; workday typologies; the catalog of breasts from taut to long; the sexually titillating and outright pornographic record that became accepted as still deeply indelible truths by Westerners worldwide.

The Western industrial machinery of sewing was introduced to the African continent in the mid-to-late 1800s, soon after it was officially declared an invention and widely patented in Europe.

According to the prevailing art-historical narratives, African women photographers did not emerge until around the Independence era, beginning in 1957 in the Gold Coast, now modern Ghana. Felicia Ewurasi Abban is the first widely documented female studio photographer, learning the trade as a teenager from her father. Later, as owner of Mrs. Felicia Abban’s Day and Night Quality Art Studio in Jamestown, Accra, she was part of the official state press corps under Kwame Nkrumah, Africa’s first Independence leader. Abban’s work was featured in the 2019 Ghana Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. However, buried in academic citations are records of women like Carrie Lumpkin, who set up a photography studio in 1907 in Lagos. The daughter of an elite physician, she was among a community of Saros—formerly enslaved persons who repatriated from Brazil to Nigeria, or their origins in other West African countries beginning in the 1830s. We do not know if Carrie Lumpkin commanded the camera or if the studio was part of her several entrepreneurships, or some blend of the two. It was not until the early 2000s that the art-historical record began to truly recognize African women photographers, who have now grown to a critical mass.

While the history of African women photographers is shrouded, explorations of archives of every kind reveal African women to be the disproportionate subjects of colonial and postcolonial image-making. It is easy to trace in this record what so often is disquieting, vulgar, violent. The photos assembled here are no doubt part of this wider ceremony of image-making, but they are presented so that our gaze shifts, and the master story begins to fall away. The machinery of the sewing machine and the camera carved out some of the most profound movement in the pursuit of modernity and resistance to colonialism and gender violence. The sewing machine allowed women to wield power, mediate power and usurp and upend the fashion systems driven by colonial powers and African men. The camera followed. In the right hands, it became a place for invention, a vehicle for the work cranked out of the sewing machine and its economy, largely powered by women.

*

Two decades ago, I began to consciously collect African studio photography. The first images were parting gifts from new friends I met when I first traveled in West Africa in the early 1990s. They were beautiful photos, that much more beloved for the manner in which they were given, with an air of romance and the sweet insouciance of the calling cards we had exchanged for one short moment in grade school in the 1970s, before they seemed to disappear from American culture. As I traveled, I also discovered local photography studios and boxes filled with unclaimed photos on the shelves inside, and became fascinated by the images that still bore the crackly remnants of cassava paste and other homemade glues used to affix them as advertisements on a shop’s exterior walls. Studio owners would let me choose from those abandoned photos for a negligible exchange, surprised or somewhat wary of my interest in them.

A decade later, I had amassed a small but significant collection, enough to be called an archive. I am not a collector by nature; I felt intimately attached to the photos, as if each person was part of a community, a home I missed. By now, many of the friendships with those pictured have in fact deepened from years of visits, and some places do indeed feel like home. Accra has come to feel like my mother’s house: familiar, returning of my love, responsible for raising me up—that is how the city lives in my psyche after nearly thirty years.

The McKinley Collection now features a trove of rare archival, vintage, vernacular, and contemporary images ranging from portraiture to postcards, images in tiny lockets, identity cards, stereographs to cartes de visite. They span the African continent from Morocco to South Africa, Guinea to Kenya, Madagascar to Benin, from 1870—a little more than fifteen years after the very first photographic studios in sub-Saharan Africa are identified—until now. Including both the masters of the studio—African photographers such as Seydou Keïta (Mali), Malick Sidibé (Mali), James Barnor (Ghana), and others—and many anonymous or lesser known ones, the collection offers, among other things, a framework through which to look forward and backward and investigate an evolution in African women’s agency and creative expression.

While the history of African women photographers is shrouded, explorations of archives of every kind reveal African women to be the disproportionate subjects of colonial and postcolonial image-making

Trying to read the images in African archives inevitably puts the viewer on a slippery slope. Colonial and African fashion systems—both modern and ancient—mimic each other; sometimes we don’t know where “tradition” begins and ends. Once accepted as empirical, evidential, we know that African studio and other photographs were highly constructed in the same way as in the West. Colonial-era photos, with their props and staging and recasting, were a “tool of Empire” that often veered from propagandistic into the absurd. The studio was a place of theater. Sometimes the photograph was only intended for private viewing. Clothing was borrowed from others or from the studio owner, traditions were eschewed for the novelty of a new display of self. Then, we must read through the multiple layers of an image— the fact that colonial studios since their introduction were run by entrepreneurs often tied closely to the state apparatus, with intentions of circulating images abroad.

At the same time, the images, particularly those from African-owned studios, capture the dignity, playfulness, austerity, grandeur, and fantasy-making of African women across centuries—in this way revealing a truly glorious display of everyday beauty.

When we explore early African photographs, especially studio images, both the politics of the body captured in the lens and the details of how the body is displayed (a woman’s glance, a button, a tattoo, the folds of a headscarf that signify a complaint or sly wisdom, or a display of true political and economic power in a few yards of cloth), we are privy in these moments to an often coded, subversive history.

The two machines, both late-nineteenth-century agents of colonial Empire, collude to create stunning, as much as sometimes unsettling, visual narratives. What is most often revealed is how deeply cosmopolitan and modernist African women were in their penchant for style, and how they were able to reclaim the tools of colonial oppression to assert selfhood and combat the ways in which their economic livelihoods were threatened. The camera and the sewing machine: the machinery of unquantifiable story-making.

Again, there is no perfect exegesis. Finally liberated from the economy in which the images were created—the long arc of propaganda in support of European imperialism and by the loving yet still heavy weight of the African male gaze—these women are now presented in this volume collectively, yet in no way definitively, representing a hundred-year story of photography on the continent.

Trying to read the images in African archives inevitably puts the viewer on a slippery slope. Colonial and African fashion systems—both modern and ancient—mimic each other; sometimes we don’t know where “tradition” begins and ends.

As art historian and curator Remi Onabanjo asserts in surveying The McKinley Collection, “You’re really getting a full sweep of time and a subversive perspective on how to investigate the history of photography, through its relation tied to black African women as subjects. Doing the work of tracing agency and power relationships, acknowledging the place of black African women inside of these networks, is one of the largest honors one can do.”

__________________________________

From The African Lookbook: A Visual History of 100 Years of African Women by Catherine E. McKinley, with an introduction and foreword by Edwidge Danticat and Jacqueline Woodson, respectively. Used with the permission of Bloomsbury Publishing. Copyright © 2021 by Catherine E. McKinley.

Catherine E. McKinley

Catherine E. McKinley is a curator and writer whose books include the critically acclaimed Indigo, a journey along the ancient indigo trade routes in West Africa, and The Book of Sarahs, a memoir about growing up Black and Jewish in the 1960s-80s. She's taught creative nonfiction writing at Sarah Lawrence College and Columbia University. The McKinley Collection, featured here, is a personal archive representing African photographies from 1870 to the present. She lives in New York City.