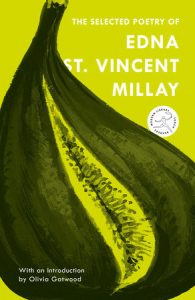

Defiant and Unsinkable:

The Ethos of Edna St. Vincent Millay

Olivia Gatwood on the Poet's Strength and Progressivism

I didn’t know who she was, but I was at her house. I had been driving for several hours and ended up at the Millay Colony for the Arts, an artist residency located at the former property of poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, tucked away in the rural Berkshires of upstate New York. I graduated college the week before and moved out of my apartment in Brooklyn. I was staying with a friend under the bridge on Broadway, where every seven minutes, her entire apartment would rattle and scream while the JMZ loaded into and out of the station. All of my things were in a storage locker on Eastern Parkway, which meant I was living out of a suitcase until I could figure where to go next. Any opportunity to leave the city was one I took. I was not attending the residency, nor had I ever heard of the poet after which it was named. But in what I would learn to be true Edna fashion, I was visiting a lover. Edna St. Vincent Millay is famous for her reflections on love, which were illuminated in her many sonnets about romantic impermanence and the heart’s unreliability. Unlike Edna, I was, at the time, terribly monogamous and heartbroken over the fact that the particular lover I was mourning then was polyamorous and uncompromising. Perhaps he was more like Millay than I was.

I didn’t learn who she was until four years later, when a public television program requested that I do a close reading of one of Millay’s most well-known sonnets, “I shall forget you presently, my dear.” That poem is a flippant and carefree take on the fickle nature of a romantic vow. By then I was in love with a woman and had a newfound empathy for Millay’s work, which often implicated queerness. In the early 1900s, that was a rare and risky thing—to write about, or to be. But Millay proved, time and time again, that social convention would not deter her.

But more than her iconoclastic attitude toward queerness, it was her breezy approach to commitment, in contrast with my delusion of love as an abiding religion, that kept me feeling, more than anything, naïve when I sat with her poems. I had to remind myself, it isn’t the job of the poet to make her reader feel good about themselves. It is the job of the poet to bring forth the heart’s most difficult truths, and for me, Millay did exactly that.

Edna St. Vincent Millay took an interest in poetry early in life, publishing her first poem at age fourteen in St. Nicholas Magazine, a publication for young people. She was encouraged by her mother to pursue the craft, eventually publishing several more poems toward the end of her teenage years. “Renascence” (1912), the title poem in her breakout collection, brought Millay her first acclaim as a writer. The poem is significantly less carnal than her later work but preludes the feeling that Millay would become famous for articulating—an urgent need to lessen the space between the individual body and everything around it, a primal hunger to grasp it all at once.

The sky, I thought, is not so grand;

I ’most could touch it with my hand!

And reaching up my hand to try,

I screamed to feel it touch the sky.

In a contest put on by The Lyric Year, the poem took fourth place, a result that many readers and even contestants believed to be unjust, which attracted a loyal fan base to Millay’s work.

She became more well known as she traveled, performing in clubs and bars to anyone who would sit and listen. This paid off when a wealthy audience member, Caroline B. Dow, offered to cover Millay’s tuition to Vassar College.

New York gave Millay permission to live as uninhibitedly as she pleased, a trait that the people around her often romanticized and sought to wrangle.As a performance poet, I get a lot of questions from audience members, particularly young people, curious how they can do what I do. I’ve always struggled with this question, because the answer feels too obvious to have to say out loud. You do it because you have to. It’s the only way you know how to communicate. But beyond that, you follow your hunger for people to hear you. You get on every stage you can, and no matter if there are four people in the audience, two of them too drunk to remember, you pretend it’s a sold-out show. When I read the story of Edna St. Vincent Millay, the traveling girl poet, I see this same hunger, and I imagine her chasing it across the East Coast, searching for a dimly lit room and a few patient ears.

After completing her degree, Millay moved to New York City, where she lived like many young writers do (as I have done)—working odd jobs and living in an apartment with a kitchen as narrow as a hallway. New York gave Millay permission to live as uninhibitedly as she pleased, a trait that the people around her often romanticized and sought to wrangle. Floyd Dell, a journalist who had grown smitten with Edna, or an idea of Edna, proposed, to which she famously replied, “Never ask a girl poet to marry you, Floyd.” After rejecting Dell’s proposal, Millay penned what would be her most sexually rebellious collection: A Few Figs from Thistles. Informed by the unruly mind of a young woman post–World War I, riddled with distrust and resistance, Figs juggled rage and comedy with indulgence and scarcity, among a hatred of Thursdays, and the bores of adulthood. Figs was chaotic—an anthem for any young woman experiencing the simultaneous confusion and exhilaration that is the Real World. Figs established Millay as a woman willing to laugh at those who sought to tame her, as much as she was willing to scream. Within Figs, in “The Merry Maid,” Millay makes a triumphant return post-heartbreak at the hands of an anonymous lover.

Oh, I am grown so free from care

Since my heart broke!

I set my throat against the air,

I laugh at simple folk!

There’s little kind and little fair

Is worth its weight in smoke

To me, that’s grown so free from care

Since my heart broke!

Second April (published 1921), Millay’s second collection, carried on her tradition of celebrating impermanence but focused instead on the natural world—the life cycles of seasons, flora, and fauna. In this collection, we see Millay’s playfulness in form—what was once dedication to the sonnet and predictable rhyme scheme becomes free verse, a telltale sign that the writer had truly let go.

In Sonnets and The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver (published 1923), the emotional hypotheses of a young Millay begin to take shape, and a woman who once brushed off all that caused her pain comes instead to grapple with the rearing of its ugly head.

Call me in all things what I was before,

A flutterer in the wind, a woman still;

I tell you I am what I was and more.

My branches weigh me down, frost cleans the air,

My sky is black with small birds bearing south;

These four collections are just a glimpse into Edna’s vast and diverse body of work, which includes plays, articles, and stories in a number of celebrated publications such as Vanity Fair, Poetry, and Outlook. But the trajectory of these specific poems honors Edna’s core emotional evolution—a girl growing into the world, a girl resisting the world, and a girl mourning the world. So much of Millay’s work realizes that we don’t have a choice which world we end up in, and because of that, we have no choice but to somehow make it our own.

I’ve always wanted to be a girl like Edna. Unfazed and unattached to the many lovers and hardships that will inevitably enter my life—appreciating them while they’re here, then thanking them when they’ve gone. Instead, I’ve spent what feels like years mourning the loss of sanity in the throes of a romance and love gone awry. We all need an Edna, if we aren’t one already. Someone defiant and unsinkable, who will take us by the shoulders and shake sense into our honeymooning hearts. What I love most about Millay, though, is that she is still loyal to talking about it, despite her instinct to brush it off. If Edna were sitting on the floor of my bedroom while I smoked and groaned out of an open window, I imagine she would laugh and tell me simply, “There will be more.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Selected Poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Modern Library.