Dear Reader,5 Recommended Epistolary Novels

Viet Thanh Nguyen, Helene Hanff, and More of Shelley Wood's Favorites

Forest fires swept through the Pacific Northwest last summer, twice scorching the tinder-dry wilderness behind my house and prompting me to store some cherished possessions with a friend who lives downtown. Old photo albums, never digitized, made the move, as did family keepsakes handed down by my mother. But most of what I drove across town to safety was my own journals—more than three decades’ worth of patchy chronicling and navel-gazing—plus a sturdy cardboard box of letters dating back to my teens.

Why all of this seemed worth protecting, I’m not sure. I can’t call to mind many of the people I wrote about so earnestly in my notebooks, nor those who replied in long, paper-and-ink letters to some outpouring of mine. Even more fascinating to me are all the gaps in this version of my life: all the months and years I didn’t see fit to commit to my journals, all the raw and expansive letters I must have sent to elicit these baffled replies.

The missing pieces, real or implied, are what I love most in an epistolary novel. By definition, an epistolary novel is one made up partly or entirely of documents—typically letters and diary entries, but also newspaper articles, and in recent years emails and instant messaging. Done well, they offer the reader the proximity of a self-consciously first-person account (and all the unreliability that entails), but also the verisimilitude implied in being some kind of formal record, a trove of documents fixed in time and place. My favorite epistolary novels make me feel like I’ve stumbled into something intimate, but must also be on my guard. No one puts her innermost thoughts in a letter any more than she can faithfully capture an objective truth in her personal journal. Epistolary novels urge their readers to play an active part in the narrative: to make the connections, be skeptical, and fill in the blanks.

Here are my top five epistolary reads.

Helene Hanff, 84, Charing Cross Road

I discovered 84, Charing Cross Road on my grandmother’s bookshelf when I was a teenager and fell in love with this witty and ultimately heartbreaking correspondence between “script-reader/writer” Helene Hanff and the staff of an antique bookshop in London following World War II. My Gran lived on the opposite side of the world, I saw her much less than I would like, and it was our letters back and forth that made us close. On my infrequent visits, I re-read this book, first assuming it was “real,” then convincing myself it was a novel. Only years later did I learn it was, indeed, an incomplete record of the real letters sent between New York and London and it is the leaps in time and the many missing letters that make it such a powerful read. Before she died, my grandmother asked me to choose a book from her shelves to remember her by and 84, Charing Cross Road (5th impression, 1975) came home with me.

A.S. Byatt, Possession

Not just my favorite epistolary novel but one of my most beloved books of all time, Possession is a book I’ve read and re-read, astonished each time by how much I’d forgotten and how easy it is to fall in love with it anew. How fitting for a book woven around long-lost letters between two Victorian poets, discovered by two ambitious academics. Letters in Possession are written and lost, written and returned, written and destroyed, even written, buried, then exhumed. Sometimes they expose a heart laid bare, other times they obscure and dissemble. For the young researchers (and the reader), everything depends on possessing, then letting go of, these long, lost love letters.

Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows, The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society

I have a friend I rely on for Netflix suggestions and in return I recommend books to her. “You’d love the movie we saw last night,” she told me recently, and I knew instantly the mistake she’d made. It’s sweet as a movie, but The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society is a different order of charming as a novel told entirely through letters, telegrams, and—briefly—“The Detection Notes of Miss Isola Pribby.” Set principally on the English Channel Island of Guernsey after World War II, the book is by turns funny and sad, but harkens back to a golden age of letter writing, when people offered up their best selves in their pithiest prose to people they were meeting for the first time, on paper.

Viet Thanh Nguyen, The Sympathizer

It’s a stretch to classify The Sympathizer as an epistolary novel, but it meets my standards on several counts. The novel, which opens in the flaming finale of the Vietnam War, takes the form of a sprawling written confession. “Dear Commandant,” writes the anonymous prisoner, who goes on to detail his life as a dual agent, both as an aide to a South Vietnam general with ties to the CIA and as a spy for Communist forces in North Vietnam. Whereas the classic epistolary novel reveals the true character of the writer through what he or she details about her subjects (or leaves out), the rhetorical device here is a narrator who tells us too much so as to tell us nothing. His lush, longwinded confession withholds even the names of his associates and, as we learn, serves to muddy the truth of his misdeeds both from his captors and himself

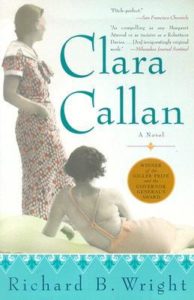

Richard B. Wright, Clara Callan

I came across Clara Callan when I was in the messy first drafts of my own epistolary novel, The Quintland Sisters, and was hunting for books that captured rural life during the Canadian Depression. My first happy surprise in this spare and meditative novel? It was epistolary, told through the Clara’s diaries as well as the correspondence between Clara and her prettier, more adventurous sister, who left small-town Ontario to become a radio actress in New York City. Clara (privately) is a poet and the sharp, haunting descriptions she allows herself in her personal journal are juxtaposed with the tight, no-nonsense letters she sends to her starry-eyed sister. Layer upon layer, they reveal the quiet courage of one woman’s life, hemmed in as much by her own choices as she is by the social and cultural barriers of the era. The second happy surprise: Clara’s decision to make a pilgrimage to Northern Ontario to visit the famous Dionne quintuplets, on whom my own novel is based.