Dealing with Mysterious Pain While Being a Writer

Sara Davis on Finding Literary Help from an Unlikely Figure

When the pain began, the winter before I turned 32, I briefly regretted ending a relationship I’d had the previous year with a chiropractor. It had been, objectively speaking, a pretty bad relationship; once he called to ask if I wanted anything from the farmer’s market and when I said that I would like some strawberries he became irate, asking if I was aware that strawberries had the highest sugar content of any fruit. No one could deny that he was a gifted chiropractor, though, and I would be lying if I said that it did not cross my mind from time to time that if by some miracle we’d made it as a couple I would have had access to free bodywork.

The first doctor I saw was in podiatry. Dr. Reilly wrote me a prescription for a “medical boot” and thought I might have rheumatoid arthritis; the rheumatologist said I did not. I saw an orthopedic surgeon, a so-called “artist of the hip replacement” (as he had been described by a friend of my parents) who looked like a tiny Viggo Mortensen in a white coat. One of his eyes was permanently closed, giving him a mildly rakish air. He told me the X-rays of my hips were normal and likely would always be fairly normal.

“These are not the kind of hips that will need replacing,” he said. I couldn’t help but feel, somehow, that I had let him down.

All the doctors thought physical therapy might help, so I started that, which made the pain worse. I decided I needed a better, more prestigious physical therapist, and so I wangled my way onto the schedule of one who was very well-regarded, the downside being that all my appointments were at 5:45 a.m. Since the pain made it impossible to drive, I took Ubers in the dark (including with one driver still in his pajamas). The prominent physical therapist was herself frequently late, but one of her aides would set me up in the treatment room, taping bags of ice to my feet, shins, and hips, and attaching electrodes to stimulate my muscles. I lay there on a massage table as night gave way to dawn, feeling so, so, cold, with the unpleasant sensation of electrical currents running through my flesh.

Once the physical therapist arrived, she would ask me some questions and then do some “soft tissue mobilization.” None of it helped with the pain and I didn’t like her; I found her grating and arrogant, but I am a natural interviewer, and there was no other way to pass the time, so we began to discuss, each morning, her fraught relationship with her aging parents.

All the doctors thought physical therapy might help, so I started that, which made the pain worse.

Eventually, I ended up seeing a chiropractor I had never dated at a clinic in San Francisco near Ghirardelli Square, on the northernmost edge of the city, where there was never any parking. His waiting room had a young, beautiful receptionist, a basket of herbal teas, and a selection of photographs of himself in Thailand. Through the door was one big, dimly lit room, where his patients would lay on seven or eight massage tables. The chiropractor would come to my table, adjust me, and then move on to the next person, circling back three or four times, before patting me on the shoulder and saying I was free to go. I spent a lot of time in that room crying in the dark on my table, listening to other people breathe, sniffle, and cough.

I read on the internet that some people with pain similar to mine had had luck with pelvic floor physical therapists, so I found one of those on Yelp. For the uninitiated, this involves a person inserting their gloved fingers into your vagina and massaging the muscles of your pelvis from this unique position. It was certainly different, but didn’t help at all, and when this became clear the PT blamed my car, a Toyota Prius.

“A lot of my chronic pain girls drive Priuses,” she said darkly, shaking the ice in her insulated cup. “Isn’t that interesting?”

*

Around the time of the chiropractor near Ghirardelli Square, I remembered a breakfast I’d had a year ago in New York with a friend, when the pain was still mild. My friend had suggested visiting a person named Edward who practiced a form of Japanese bodywork derived from a modality called “anma,” a treatment, Wikipedia helpfully explained, for which there was no medical evidence of effectiveness.

I mentioned Edward to the osteopath I’d been seeing, and it turned out that years ago the two men had shared a clinic. Back then, the osteopath said, Edward had been known in the community by his nickname, Edweird. The osteopath was also memorable—he had one of the most beautiful offices I have ever seen of anyone in any profession; huge floor to ceiling windows gave the impression that we were in a woodland paradise, embedded within a dewy green copse where birds and squirrels gamboled beside a large Buddha head that rose from the grass. His third wife was also his receptionist. The osteopath’s diagnosis was the wildest of all.

“Did you have braces as a child?” he asked.

“On my teeth?” I replied, confused. “Yes.”

“Did you have teeth removed?”

“Yes, four.”

“A lot of my chronic pain girls drive Priuses,” she said darkly, shaking the ice in her insulated cup. “Isn’t that interesting?”

I could still remember distinctly lying in my parents’ bed, chipmunk-cheeked and eating ice cream through a straw.

“That’s probably it then,” he said. “That’s the source of the pain.”

I struggled to toggle my facial expression from WTF to neutral while he opened a filing cabinet drawer and took out a black and white photograph of two similar-looking women.

“These are identical twins,” he said. “This one”—he pointed to the woman on the left, who looked thin and sad—“Had aggressive orthodonture. This one”—he pointed to the happier, more buoyant looking twin on the right, “Did not.”

Anyways, Edweird.

The day we met it was raining. A cold gray light had settled in the waiting room of the suite Edward shared with a beautiful, German, vaccine-flexible pediatrician.

“Sara?”

A 69-year-old man appeared, with shoulder-length snow-white hair, wearing a short-sleeved linen button-down over a prominent belly, like a cross between Santa Claus and a pan flute-playing musician at a farmer’s market. On his feet he wore black socks and Birkenstocks.

“Clothes are good,” he said appraisingly, meaning mine—he had requested over the phone that I wear loose cotton clothes, long sleeves, and long pants. “Come in.”

His room was peaceful, with silk-screened textiles on the walls and a seascape in oils, painted by his wife. I moved with effort onto the soft treatment table, which Edward sticky-rollered between clients, and lay down on my back.

Edward’s particular kind of bodywork is difficult to describe. It was not unlike a very slow, very targeted massage, with a lot of pressing. That was the physical side; on the metaphysical side, it involved a kind of bodily clairvoyance. Halfway through our first session he looked up, surprised, from methodically applying pressure to my femur, and said, as if it surprised him, “You’re in a lot of pain.”

Maybe he said the same to everyone, but I was kind of overcome. Because I looked normal and had no medical diagnosis for my problem, I had the impression that people were skeptical—not just doctors, but also friends. I was in a lot of pain, and to hear someone else say it was a solace of a magnitude I could not have anticipated.

Edward’s particular kind of bodywork is difficult to describe. It was not unlike a very slow, very targeted massage, with a lot of pressing.

It was not until our second session that Edward diagnosed me.

“What do you do for work?” he asked.

I explained that I worked at a store in San Francisco, but that I was currently taking time off because the pain made it difficult to drive and I was spending a small fortune on Ubers. In the beginning my mom had driven me to a few of my appointments, but after we had a huge, high-volume fight about whether or not I needed to brush my hair before meeting a new doctor, I had elected to eschew her help.

“What kind of store?” Edward asked.

The store was hard to explain because it was called “General Store” and it sold a bit of everything: clothes, shoes, ceramics, used books, even plants.

He frowned. A lot of people frowned when I told them I worked at a store. It was not what they expected from a person who had gone to a fancy college and then returned to the same fancy college for a nebulous master’s. One family friend kept asking, as if repeating the inquiry might engender a new response, “Really? A store?”

I refused to voluntarily disclose that I was working on a novel because that seemed like a mortifying thing to disclose, especially since by then I had been working on the same novel for six years and it was becoming increasingly unclear whether I would ever finish. At the time the pain arrived I was close to giving up. I had been a waitress, a teacher, a dog walker, cat sitter, and now I was working at a (very charming and Instagram-prominent) store. I never mentioned writing to strangers except under great duress. I had once been shocked to sit next to a man at a dinner party who, when I asked him what he did, proclaimed loudly, “I write books!”

Edward, his thumb and index finger meditatively wiggling my toe bone back and forth, asked, “Is that your life’s work?”

“Um,” I said. “No. I’m trying to write a book but it isn’t going very well.”

Edward had the kind of tufted white eyebrows that older men sometimes have, and at this point they moved several centimeters up his forehead.

I refused to voluntarily disclose that I was working on a novel because that seemed like a mortifying thing to disclose, especially since by then I had been working on the same novel for six years and it was becoming increasingly unclear whether I would ever finish.

“Well,” he said. “That’s probably it then.”

One of my meridians was blocked. My creative energy was unable to flow. Finish my book and I would heal my pain.

I did not say anything. What could one say? Was it the most plausible explanation I’d heard? No. Was it the least plausible? Also no.

*

In graduate school, when I started the book, I felt very cool and confident. I was pretty good at writing; I had a mildly famous boyfriend and had interned at Teen Vogue when Lauren Conrad and Whitney Port were filming The Hills. By the time I saw Edward and I was 31, I had never made more than $30,000 in a year; I was, to my surprise, completely unfamous, while people in my peer group got married, bought homes, founded startups that went public, and were somehow already architects.

Meanwhile, I was dating a series of bizarrely damaged men I’d met on dating apps (the art handler who kept his ex’s entire collection of nail polish; the containership navigator who was suing his ex and his uncle; the aforementioned chiropractor, who once sent me an email that included the sentence: “Excessive sugar/carb intake causes adrenal fatigue and insulin imbalance, and there’s also a direct correlate between casual sex and lower feelings of self-esteem, life satisfaction, and happiness.”) I was, as they say, at something of a crossroads.

It turned out that Edward had more advice for me.

“Do you have an editor?” he asked. When I tried to explain that usually for the kind of book I was writing I would need to finish writing it before an editor would become involved, he was unconvinced. It turned out that he had recently watched the movie “Genius,” starring Jude Law and Colin Firth, about the tempestuous relationship between the writer Thomas Wolfe and his editor Maxwell Perkins.

“Maybe you need an editor,” he said, as I tied my shoelaces.

He also recommended that I buy some Birkenstocks, and, if possible, to spend some time walking on the sand.

*

Edward was the only practitioner who was helping, and I went to him devotedly—two, sometimes three times a week at first. He talked steadily through each appointment, wide-ranging stories from his past, or just some of his current areas of concern. I could have told you his entire life story: his youth in Belgium, his time living off the land in the Alps, his years in Japan, where he met his wife and studied healing. He wasn’t a bad storyteller, and the narratives required no input from me to keep flowing. Once, as I lay on the table with my eyes closed, he cold-opened with, “What if we’re all aliens and this life is a dream?”

By the time I saw Edward and I was 31, I had never made more than $30,000 in a year; I was, to my surprise, completely unfamous, while people in my peer group got married, bought homes, founded startups that went public.

Eventually, I printed out the 150-odd pages of my novel-in-progress, carefully arranged myself on my couch in the one specific reclined position in which I could be relatively comfortable and began to read. Anyone who’s been hiding from a creative project for a long time knows that that first look is scary. But as I read, I was surprised to find myself thinking—hey! This isn’t bad!

*

There’s a man-made “dry” lake on the Stanford campus, with one side bordered by sloping frat house lawns. The loop around it, a dirt trail, is less than a mile long. That year, due to the heavy winter rains, the lake was a swampy morass of mud. The first time I had some concrete feeling I was improving, physically, was when I could walk around it, which I could just barely do in the fall of that year (although I had to rest at home for a full day afterward). I wore my Birkenstocks, of course, which I had been wearing religiously every day since meeting Edward. When I finished the walk around the lake my feet and Birkenstocks were covered in mud.

For every chronic pain person on the internet banging the drum about a diet, exercise, or individual who healed them, there is a sad, bitter person whose pain never went away. I’m a hybrid of the two—I fully credit Edward and Birkenstocks with my return to relative physical normalcy, but the pain never did go away. At a certain point I just couldn’t devote any more energy to it, and in its less acute form, it’s manageable.

If someone had told me in January when the pain began that it would never leave me, it would have felt like a death sentence. Now, I’m pretty confident it will be with me always and that’s okay. One of Edward’s most favorite disquisitions was on the distinction between pain and the fear of pain; how, in the end, it was the fear that could be more damaging. He no longer feared pain. I no longer fear my pain—I would never go so far as to say that we are friends, but we’re familiar with each other, the way you might feel about a grocery store that you don’t love but that you’ve been to a lot of times, so you know where everything is.

I sold my book a year and a half or so after the pain began. It is my belief that had the pain not entered my life at the moment it did, I might never have finished. I still have never made more than $30,000 in a year, and I continue to not be an architect. But my novel was published this week, and that’s the only (professional) thing I’ve ever wanted. I don’t live in California anymore, so I can’t have Edward check the relevant meridian to see if there’s been any movement.

The part of my life where I considered giving up on writing—where I couldn’t even tell if I liked my own writing or not—is over; it’s been over for a while.

__________________________________

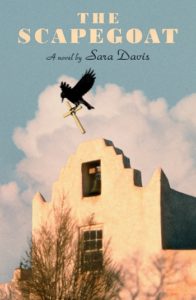

The Scapegoat by Sara Davis is available now via Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Sara Davis

Sara Davis grew up in Palo Alto, California and received her BA and MFA at Columbia University. She has taught creative writing in New York City and Detroit. She has been awarded residencies from Ucross, Vermont Studio Center, and Ragdale. She lives in Shanghai, China. The Scapegoat is her first book.