Dead Men of Leisure on Their Love of Fishing

"I felt a great fish at the end of my line but it dropt in, and

the disappointment vexeth me to this very day."

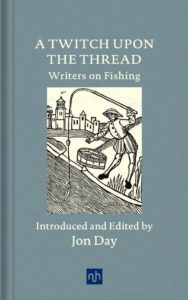

The following are from A Twitch Upon the Thread: Writers on Fishing, available now from NYRB.

Charles Dickens

From A Dictionary of the Thames (1893)

Sturgeon occasionally come up the Thames, but they were never numerous in this river. Provision was made in ancient Acts excepting them from the vulgar fate of other fish, and in the instructions to the City water-bailiffs for the time being, orders were issued that the sturgeon “was not to be secreted,” and that all royal fishes taken within the jurisdiction of the Lord Mayor of London, as namely, whales, sturgeons, porpoises, and such like, should be made known, and the name and names of all such persons as shall take them shall be sent in to the Lord Mayor of London for the time being.

The sturgeon therefore is always, when taken, sent direct to grace the table of majesty. The presence of mud (if it is clean mud) does not, from their bog-like habit of ploughing up the deposit of the stream, form any obstacle to their progress into fresh water, nor does the latter appear to affect them, even immediately from their presence in the sea.

They have never been known to be taken by line and bait, but they often get entangled in the nets of fishermen, which they greatly mutilate, from their amazing strength, in their efforts to escape.

The flesh of the sturgeon is looked upon with suspicion little short of aversion by some persons, but it, according to the parts submitted to the operations of the cook, may be rendered into the choicest of dishes—one portion simulating the tenderest veal, another that of the sapid succulence of chicken, and a third establishing its reputation to a claim to most of the gastronomic virtues of the flesh of many acceptable fish in combination.

The great chefs, Francatelli and Ude, used to aver that there were 100 different ways of rendering sturgeon fit for an emperor; and Soyer would boast that he had added two more methods of its culinary preparation to these apparently exhaustive receipts.

Henry David Thoreau

From Walden (1845)

Sometimes, having had a surfeit of human society and gossip, and worn out all my village friends, I rambled still farther westward than I habitually dwell, into yet more unfrequented parts of the town, “to fresh woods and pastures new,” or, while the sun was setting, made my supper of huckleberries and blueberries on Fair Haven Hill, and laid up a store for several days.

The fruits do not yield their true flavor to the purchaser of them, nor to him who raises them for the market. There is but one way to obtain it, yet few take that way. If you would know the flavor of huckleberries, ask the cowboy or the partridge. It is a vulgar error to suppose that you have tasted huckleberries who never plucked them.

A huckleberry never reaches Boston; they have not been known there since they grew on her three hills. The ambrosial and essential part of the fruit is lost with the bloom which is rubbed off in the market cart, and they become mere provender. As long as Eternal Justice reigns, not one innocent huckleberry can be transported thither from the country’s hills.

Occasionally, after my hoeing was done for the day, I joined some impatient companion who had been fishing on the pond since morning, as silent and motionless as a duck or a floating leaf, and, after practicing various kinds of philosophy, had concluded commonly, by the time I arrived, that he belonged to the ancient sect of Cœnobites.

There was one older man, an excellent fisher and skilled in all kinds of woodcraft, who was pleased to look upon my house as a building erected for the convenience of fishermen; and I was equally pleased when he sat in my doorway to arrange his lines. Once in a while we sat together on the pond, he at one end of the boat, and I at the other; but not many words passed between us, for he had grown deaf in his later years, but he occasionally hummed a psalm, which harmonized well enough with my philosophy.

Our intercourse was thus altogether one of unbroken harmony, far more pleasing to remember than if it had been carried on by speech. When, as was commonly the case, I had none to commune with, I used to raise the echoes by striking with a paddle on the side of my boat, filling the surrounding woods with circling and dilating sound, stirring them up as the keeper of a menagerie his wild beasts, until I elicited a growl from every wooded vale and hillside.

In warm evenings I frequently sat in the boat playing the flute, and saw the perch, which I seem to have charmed, hovering around me, and the moon travelling over the ribbed bottom, which was strewed with the wrecks of the forest. Formerly I had come to this pond adventurously, from time to time, in dark summer nights, with a companion, and, making a fire close to the water’s edge, which we thought attracted the fishes, we caught pouts with a bunch of worms strung on a thread, and when we had done, far in the night, threw the burning brands high into the air like skyrockets, which, coming down into the pond, were quenched with a loud hissing, and we were suddenly groping in total darkness.

Through this, whistling a tune, we took our way to the haunts of men again. But now I had made my home by the shore.

Sometimes, after staying in a village parlor till the family had all retired, I have returned to the woods, and, partly with a view to the next day’s dinner, spent the hours of midnight fishing from a boat by moonlight, serenaded by owls and foxes, and hearing, from time to time, the creaking note of some unknown bird close at hand.

These experiences were very memorable and valuable to me—anchored in 40 feet of water, and 20 or 30 rods from the shore, surrounded sometimes by thousands of small perch and shiners, dimpling the surface with their tails in the moonlight, and communicating by a long flaxen line with mysterious nocturnal fishes which had their dwelling forty feet below, or sometimes dragging 60 feet of line about the pond as I drifted in the gentle night breeze, now and then feeling a slight vibration along it, indicative of some life prowling about its extremity, of dull uncertain blundering purpose there, and slow to make up its mind.

At length you slowly raise, pulling hand over hand, some horned pout squeaking and squirming to the upper air. It was very queer, especially in dark nights, when your thoughts had wandered to vast and cosmogonal themes in other spheres, to feel this faint jerk, which came to interrupt your dreams and link you to Nature again. It seemed as if I might next cast my line upward into the air, as well as downward into this element, which was scarcely more dense. Thus I caught two fishes as it were with one hook.

Jonathan Swift

A Letter to Lord Bolingbroke (1841)

I remember when I was a little boy, I felt a great fish at the end of my line which I drew up almost on the ground, but it dropt in, and the disappointment vexeth me to this very day.

Robert Louis Stevenson

A Letter to J.M. Barrie (1894)

It was a charming stream, clear as crystal, without a trace of peat—a strange thing in Scotland—and alive with trout; the name of it I cannot remember, it was something like the Queen’s River, and in some hazy way connected with memories of Mary Queen of Scots.

It formed an epoch in my life, being the end of all my trout-fishing. I had always been accustomed to pause and very laboriously to kill every fish as I took it. But in the Queen’s River I took so good a basket that I forgot these incites; and when I sat down, in a hard rain shower, under a bank, to take my sandwiches and sherry, lo! and behold, there was a basketful of trouts still kicking in their agony.

I had a very unpleasant conversation with my conscience. All that afternoon I persevered in fishing, brought home my basket in triumph, and sometime that night, ‘in the wee sma’ hours ayont the twal,’ I finally forswore the gentle art of fishing.

Lord Byron

From Don Juan (1824)

The following is a note on Izaak Walton: This sentimental savage, whom it is a mode to quote (amongst novelists) to show their sympathy for innocent sports and old songs, teaches how to sew up frogs, and break their legs by way of experiment, in addition to the art of angling, the cruelest, the coldest, and the stupidest of pretended sports.

They may talk about the beauties of Nature, but the angler merely thinks about his dish of fish; he has no leisure to take his eyes from off the streams, and a single bite is worth to him more than all the scenery around. Besides, some fish bite best on a rainy day. The whale, the shark, and the tunny fishery have somewhat of noble and perilous in them; even net fishing, trawling etc., are more humane and useful, But angling! No angler can be a good man.

__________________________________

Extracts taken from A Twitch Upon the Thread: Writers on Fishing. Introduced and edited by Jon Day. Published by Notting Hill Editions. Available from New York Review Books, www.nyrb.com