Darryl Pinckney on Working for the New York Review of Books and Navigating New York City’s Literary Scene as a Young Black Writer

“Bob and Barbara are dinosaurs and we’re these mammals running around afraid of getting squashed.”

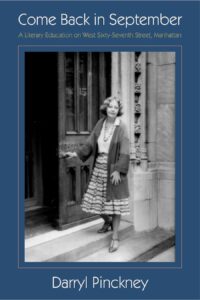

Featured image: Dominique Nabokov, The New York Review of Books

I’d seen Barbara Epstein for the second time, this time in the chaotic offices of The New York Review of Books. They were on the fourteenth (thirteenth?) floor in the faintly ratty Fisk Building, on the corner of West Fifty-seventh Street and Broadway. A girl I’d become friends with when she was Professor Hardwick’s lodger worked there in the charged silence. One evening a petite figure, Barbara Epstein, crossed the main room to her office. She advanced chin-first. She wore black pants. She carried papers and was chewing gum. She’d quit smoking, it was whispered. One story had Robert Silvers setting fire to the hair of an editorial assistant who happened to lean over his desk just as he moved forward in his chair with his burning brown Sherman.

And Seduction and Betrayal: Women and Literature had been published, Professor Hardwick’s first book in more than a decade. The dedication:

To my friend Barbara Epstein, with love

It would take me a while to understand this collection as an act of self-rescue. Divorce, a prism that rayed her understanding of being a woman, a state she and Barbara would talk from probably more than they talked about.

*

Barbara gave me the nickname Fortunoff, the Source, following the two weeks in the autumn when I worked in the Review’s mailroom with Howard Brookner, someone her son knew from Exeter, the guy I was sharing an apartment with on a street sloping downhill from the Columbia campus. My handsome roommate was a senior, but I was supposed to be wading into the real world.

Bob and Barbara were The New York Review of Books and then there was everybody else.

The mailroom was out of control. Employees helped themselves to books, telephone calls to Hong Kong, extra sandwiches during press week. They had a softball team. My duties included babysitting for the publisher’s assistant’s children. I’d once been babysitter to Barbara’s daughter, then a preteen in a Spence School uniform and red high-top sneakers.

(I want to remember Helen Epstein as reading Miriam Rothschild. She is sure that she was doing a bunch of math homework.)

Bob and Barbara were The New York Review of Books and then there was everybody else, with the publisher doing his best in the engine room of an outfit famous for getting galleys by messenger to its writers no matter the challenge. It was a poor paper that spared no expense when it came to moving print around the globe. These were the days before desktop computers, before faxes, not that long ago, or maybe by now it is, my youth is longer and longer ago, when George the III was king, and not to xerox a letter from Mr. Silvers or galleys so interrogated they looked embroidered before everything was expressed to Oxford or to Washington, D.C., was to put press week in jeopardy.

The telephone was everything in the editors’ hourly reasonings with proud and anxious writers. Meanwhile, the young who worked there were either so terrified or so cunning, their business took place as a humming of heads turned toward walls, telephone receivers cradled, or they hid behind hedgerows of books. The softball team’s captain, a tall blond painter, and a modern dancer with a thick mustache were the mailroom staff, one needing some more time off, the other not back yet. The painter showed my fellow temp and me the switchboard, calling out over the intercom for either Robert Silvers or Barbara Epstein on line one or line two, assuring us that after a few minutes we wouldn’t give a singing rat how urgent any package was. I knew Elizabeth phoned Barbara almost every day.

—How is Felicia Bernstein? I had the temerity to ask of Barbara one five o’clock. There was no reason on earth why I should have inquired after a friend of hers whom I knew to be seriously ill.

Bob and Barbara are dinosaurs and we’re these mammals running around afraid of getting squashed, I, trying to buddy up, said to Prudence Crowther, a satirist who worked as a typesetter in the production studio. She smiled but withheld her laughter. An office of the tensed up went nuts at Prudence’s huge laugh, slamming doors or screaming that some people were trying to concentrate and then slamming doors. Her hair was cut like that of the actor Louise Brooks, who was then undergoing a big revival, but with Prudence that would have been just coincidental.

Prudence tended the studio door, its layers of bizarre headlines, weird cutouts, clippings about the outrageous. The office style was funky, a work in progress, and that of many hands over time. The mailroom walls were dark collages. The office featured a long, wide central space with doors leading from it, or feeding into it. You saw stained, scrawled-upon whitish walls, boxes of whatever, long metal tables of whatever, file cabinets, stray books, already-grimy galleys of books, a water cooler, walls plastered with photographs, posters, against the back wall a cracked white sofa that people with appointments didn’t like to sit on, and beside the unhappy sofa a refrigerator second only to my mother’s in the high percentage of rot among the contents.

—How is Elizabeth? James Baldwin had asked politely when I was a student and raced over to his table in the Ginger Man, a restaurant near Lincoln Center. I had a volume of Byron’s Journals with me and opened it for Baldwin to sign as I announced whose student I was and assured him I’d give greetings he had not yet offered to Elizabeth Hardwick. He wrote down his address and telephone number on a slip of paper that he tore from a small notebook.

I had to learn the rules. Don’t discuss someone you don’t know well with someone who knows that person better.

She most certainly was not going to call him, very disapproving that I had used her name. She laughed that he was never on time, Jimmy and his inevitable entourage.

I once explained to her the concept of CPT.

—You came to New York to be what you are, she said. A mad black queen.

Harriet’s best friend from Dalton said that I’d only read the Monarch Notes about everything, because I was too busy memorizing Seduction and Betrayal.

(A few years later, I couldn’t keep up my end talking about Joseph Heller with my eldest sister, Pat, except to quote one of Elizabeth’s witticisms about Something Happened and Pat said she understood that Elizabeth was my teacher and all but maybe I should go back to reading books for myself.)

I used to haunt the Review in the evenings when Celia McGee (née Betsky), Elizabeth’s former student boarder, worked for Robert Silvers. I was perplexed when she told me she ironed her clothes for work every morning. She was Jewish, had grown up in Holland, and she knew more about black literature than I did and my junior year she got me invited to the Alain Locke Symposium on African American Literature, sponsored by The Harvard Advocate, an experience that changed my attitude toward the subject I was born with, as Baldwin once described writing about black literature. At Harvard, Ralph Ellison had drawn himself up to a great height and explained to the assembled that the reason he would not say he was African American was that he was not, he was a Negro.

Celia had moved on, moved up elsewhere, but I still hovered around the mailroom now that hardworking Sigrid Nunez, another former student of Elizabeth’s, was waiting on Bob, Mr. Silvers. Elizabeth was much interested in the question of what Sigrid would go on to write. She’d studied dance. She was in earnest concerning all things Virginia Woolf. I tried to be equally intense and would jabber about, say, the sadness of the boots at the end of Jacob’s Room.

(But a page from my burned journal says I met Sigrid Nunez in Professor Hardwick’s office on April 7, 1975, and then Professor Hardwick went to class. The past in my head can’t be all prestidigitation.)

I repeated office gossip to Elizabeth, about staff and contributors and strangers.

I had to learn the rules. Don’t discuss someone you don’t know well with someone who knows that person better. Don’t let anyone know that you have been talking about her or him even if what was being said was praise.

—Gossip is just analysis of the absent person, Barbara and I always say. Then we let the absent person have it.

*

I pilfered a copy of the notorious issue of the Review from August 24, 1967, with the drawing on the cover of how to make a Molotov cocktail. I presented it to Luc. It was also the issue in which Kopkind assured us that even Dr. King acknowledged he’d failed. Luc was not fazed that back in those days the staff used to get high in the office. Bob and Barbara were said not to have noticed.

—What about now.

(Editorial assistants had no billing on the masthead when Joan Jonas and Deborah Eisenberg and Jean Strouse worked for Robert B. Silvers.)

That paperback of The Souls of Black Folk waited and waited, saying what I thought I needed it to, that the spirits could read.

When his glasses slipped down his nose, Luc wouldn’t push them up right away, he’d raise his head and his wire rims made his facial expressions even more inquisitorial.

Columbia’s blue flags were at half-mast, English department colleagues were rushing into print with remembrances. Luc and I passed behind St. Paul’s, the campus chapel, just as the bells began to sound.

—Hark, hark, the bells are Trilling, Luc said without inflection, looking straight ahead.

Hannah Arendt died suddenly, a few weeks before Christmas. Her name came up often in the pages of The New York Review of Books. That sweltering first summer in New York on my own, Arendt had published an essay that I got my Ramparts-reading older sister interested in, about the political disarray in the United States after the lies of Watergate and defeat in Vietnam. The tribute to her in the Review was by Robert Lowell, not Elizabeth Hardwick, who once told me that everything in Arendt’s Riverside Drive apartment was beige, including the food.

Arendt had been a way out of the inadvertent Stalinism that my love for Angela Davis had led me into. But I returned The Origins of Totalitarianism to Elizabeth’s shelves. Yet I, clown, added Arendt’s insights to my bar chatter, such as the distinction she makes in Between Past and Future between leisure time, when we are free from cares, and vacant time, which is leftover time after work and before sleep that we fill with entertainment. It was usually okay, because in most of the bars I ran through no one was making much sense, either, or weren’t interested in that.

In Crises of the Republic, Arendt identifies the information that technocrats and advisers deal in as non-facts. What does it matter if we have the capacity to blow up the world thirty-two times when once will do. Everyone at parties was into that one. But the book caused me some discomfort, not because of her stern analysis of Black Power and violence, but because Arendt argues that minority admission programs represent a threat to universities and put black students in the position of having to be constantly aware of their inferiority.

Men in Dark Times was brilliant, just as Elizabeth promised. The Randall Jarrell essay; doomed Rosa Luxemburg. And I was moved by The Human Condition. But the work of Arendt’s that I was most curious about was Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewess, which Elizabeth said she’d not read in a long time. Arendt’s biography spoke to me, her tale of a not-pretty Jewish girl who came of age in late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Germany, when Jews were eager for emancipation, but only the privileged among them were allowed limited participation in German society. Moreover, this biography of yearning for unavailable, aristocratic men was full of those things that fascinated me: diaries, letters, and salon gossip. Varnhagen resolved to tell the truth of her experience, loser in love that she was.

But Varnhagen did more than dignify my flight into myself, which her life promised would end in self-acceptance. To read about Moses Mendelssohn and the problems of Jewish assimilation had the effect of making me interested in W.E.B. Du Bois at last. Or maybe I hadn’t forgotten my resentment of her Crises of the Republic. I had everything of Du Bois’s that Herbert Aptheker had edited, like trophies. And that paperback of The Souls of Black Folk waited and waited, saying what I thought I needed it to, that the spirits could read.

The abstract, theory, did not interest Elizabeth Hardwick for long. In this sense, she was left out of what had brought her old friend Mary McCarthy and Arendt together, the philosophical quest for the truth behind appearances. She told me that after Hannah’s husband died, Mary had Hannah up to stay in Castine, the little town on the water in Maine where Mary and Elizabeth both spent their summers. Hannah was lying on the sofa, her hands behind her head, staring at the ceiling.

—What’s she doing? Elizabeth asked.

—She’s thinking, Mary whispered.

Elizabeth said she felt not a little put down by the answer.

She was left out of what had brought her old friend Mary McCarthy and Arendt together, the philosophical quest for the truth behind appearances.

In McCarthy’s ‘Farewell to Hannah Arendt,’ which was published in The New York Review, she says that Arendt had pretty feet and loved shoes.

I think she only once had a corn.

Elizabeth was terribly put off by the detail, which she thought said more about the state of Mary’s feet than it did of Hannah’s. In any case, it was somehow indelicate to her way of thinking, she who retreated from too much frankness about the body on the page. It was a minor example of what Elizabeth said could be the obtuseness of Mary’s insistence on truthfulness in all things.

She said that up in Castine, friends fell out with one another from time to time for silly reasons. Mary would march past the someone she was on the outs with and get in the car without speaking, while Elizabeth waved to the banished party behind Mary’s back.

—Just as two-faced as I can be.

Elizabeth was glad her visiting professorship for a term at Smith College was over. To employ me, she had me drive her up with her bundles, her typewriter, and her orange plant. We rented a car and she tried to jump from it when someone speeding along next to us gave some mysterious signal that made her panic. She opened the door, at seventy-five miles an hour.

—Are we on fire?

On my command she yanked the door shut and I sped up. I was no driver. We never did that again.

Northampton, Massachusetts, was too far to commute and life at a small liberal arts college was not to be believed. She recommended Randall Jarrell’s satirical novel about just such a place, Pictures from an Institution. When I came back with it, we went over some favorite scenes.

—Ass kisser, Harriet, the college freshman, said as I prepared to do the dishes.

—No, he’s not, Elizabeth said. We’re just mutually supportive.

_____________________________________

Excerpted and adapted from Come Back in September: A Literary Education on West Sixty-Seventh Street, Manhattan by Darryl Pinckney. Copyright © 2022. Available from by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, a division of Macmillan, Inc.

Darryl Pinckney

Darryl Pinckney, a long time contributor to The New York Review of Books, is the author of novels, Black Deutschland and High Cotton and the nonfiction works Busted in New York and Other Essays, Blackballed: The Black Vote and US Democracy, and Out There: Mavericks of Black Literature.