Darkest New England: What is the Northern Gothic Literary Tradition?

W.S. Winslow Tries to Define a Recondite Genre

Darkness. Madness. Specters. Death. Add some menacing weather, a tortured anti-hero and a long-buried secret or two and you’ve got the makings of a fine old Gothic novel in the tradition of Jane Eyre or The Hunchback of Notre Dame, big, chewy tales that roll right up to the precipice of horror but stop just short, lingering instead in the realm of Europe’s Dark Romanticism. Cross the line into horror and you leave the gloom of Manderley and Wuthering Heights for the hallucinogenic terror of The Castle of Otranto, Dracula’s Transylvania or Doctor Jekyll’s lab.

American fiction has its own Gothic tradition. Best known is the southern version, set not in cathedrals, castles and moors, but amidst the decrepit plantations and enduring ruin of the Civil War. Whereas the Southern Gothic is draped in Spanish moss, surrounded by cotton fields and oppressed by summer swelter, the Northern Gothic was born of cold and Calvinism, isolation and endurance, rooted not in the horrors of slavery and a fetishized myth of southern gentility, but the sharp, hard edge of fundamentalist Protestantism and the hopelessness of predestination. It’s the Salem of Goodman Brown, Poe’s House of Usher, and Ambrose Bierce’s Owl Creek Bridge.

Despite the general decline of organized religion in recent years, cultural Puritanism persists in much of New England and is foundational to its history. Ever since the European invasion of the New World, the roots of that belief system have been snaking underfoot, pushing so deep into the ground that they nearly choked out other traditions: those of the First People, later arrivals from Catholic Europe and French-speaking Canada, and the Black and Brown descendants of the Great Migration. If you like your literature fraught with doom, New England is a good place to find it.

I ought to know. My own family is descended from the earliest settlers in the New World and has been living in Maine since the beginning of the 18th century. Most of our people were Puritans, but there were also some French Canadians and Quakers, the latter contributing a marked strain of intransigence to a bloodline already amply endowed with it. Starting in Salem Town the historical record of my family includes a litany of contrarian behavior that resulted in fines, periodic imprisonment and occasional flogging, which is why, I suppose, a couple of generations after they disembarked in Massachusetts, my forebearers started moving steadily north to un- or sparsely inhabited places in what later became Maine. And here we have stayed for ten generations.

There is, I find, a particularly hard-headed mindset among many Mainers, especially those descended from people who chose to live in this harsh, remote place, spending much of the year in the long dark of winter, waking to ice in the wash basin, battling the ever-encroaching forest, and ploughing the rocky soil for a short, frantic growing season. Their legacy is a way of living and thinking that rejects the emotional excesses of Romanticism, rewarding instead the pragmatism of the realist.

American fiction has its own Gothic tradition. Best known is the southern version, set not in cathedrals, castles and moors, but amidst the decrepit plantations and enduring ruin of the Civil War.

Which is not to say we don’t have our fancies, our ghosts. We do. In fact, some might argue that New England, by virtue of being the longest-settled corner of the country, and one of the least hospitable, has its own particular dark past. In the early years of the Massachusetts colony, religious “heretics” were routinely flogged, mutilated and murdered; innocent townsfolk—mostly women—were hanged as witches; and Native people were brutalized, expelled from lands they had lived on for millennia, and nearly exterminated. Later, in the 1920s, a xenophobic, nationalist Ku Klux Klan rose in New England turning their hate mainly on Catholic immigrants and anyone who was not “100 percent American.” Like our southern countrymen, we’ve got plenty of skeletons in our collective closet. And so, in the Northern Gothic tradition, Hawthorne begat Poe, Poe begat Lovecraft, and from Lovecraft it was a short walk through the graveyard to Stephen King.

Many years ago, when I was a student at the University of Maine, I heard a ghost story. In it, a friend told of standing at the stove in her 200-year-old rented house, frying up falafel, when she noticed a phantom in the doorway, a uniformed Civil War soldier, calmly watching her cook. My friend was, and is, one of the most rational, down-to-earth people I have ever known, and so neither I nor any of our friends ever doubted her story. Perhaps the soldier was drawn by a need for human contact, or maybe it was the smell of cumin and garlic that caused him to appear. In any case, from then on we called her place the ghost house.

At the time, I wasn’t so much spooked by the story as intrigued by it. For me, that single incident defined the place, and to this day, the image of the solitary ghost-soldier in the kitchen is central to my personal mythology of that time and place.

The story also tidily sums up the essence of what the Northern Gothic is for me, the way ghost stories have, over the years, come to normalize the fantastical. Our spooky tales are like pieces of starched white linen, with stories of madness, death, despair and hauntings embroidered in delicate stitches around the edges and in small cutwork inlays—realism and plainness framed in supernatural foreboding.

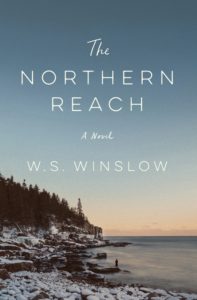

This image was on my mind while I was writing The Northern Reach, my novel in stories. I wanted to show how, in a forgotten corner of my home state, places and people change over time, or how they don’t, the ways the past repeats, and how even long-buried secrets haunt the present, lurk on its outskirts.

The town of Wellbridge is fictional but typical, once prosperous, now slowly dying. The economic and social divides between the hardscrabble locals and the wealthy summer people in their Bridge Point cottages widen by the day. Among the townspeople there is yet more stratification, though it is overlaid with a spiderweb of relationships among four of the town families. Isolation pervades Wellbridge, from the short dark days of winter through the brief bright of summer.

Our spooky tales are like pieces of starched white linen, with stories of madness, death, despair and hauntings embroidered in delicate stitches around the edges and in small cutwork inlays.

I wanted to set a Gothic mood from the beginning of the book, and so I opened it with Edith Baines, my anti-heroine, whose story runs through several of the episodes and whose life connects many of the townspeople. It doesn’t matter whether Edith’s morbid boat watch and subsequent encounter with the ghost of her dead son are real or the product of her unraveling, grief-stricken mind. What does matter is that they’re real to her.

Running through the book is a thread of madness, usually untreated, sometimes mistreated. This was not unusual in Maine, or any other state, in most of the 20th century when asylums were historically the last stop on the road to a slow, wretched death. In Wellbridge, there is also the constant threat of winter and the frigid, roiling bay, both characters as real as the people who live with and by them.

From time to time ghosts appear, both in spectral form and in memory, hovering on the edge of reality, the black chain stitch on the cloth of everyday life. Wellbridge and its people are haunted by the past, and that, too, is common in the Maine I know. Here, the past and the hard reality of daily life is tangled up with mental illness, the supernatural, and hauntings, both real and imagined. And if sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference, that’s intentional. It’s one thing to see a ghost, but quite another to wonder whether you’re really just losing your mind.

But the world of Wellbridge is not all darkness and despair, and that’s because Mainers are some of the funniest people I know. Among my family and friends, it’s nearly reflexive to dismiss the painful or the unbearable with a joke, usually one that’s darker even than what we’re trying to avoid. Like all of us, the people of Wellbridge do the best they can. Faced with tragedy and despair, they rail, they fight, they succumb, and they mourn in the darkness. When all else fails, they laugh in its face, or as Edith Baines’s granddaughter does in the book’s final passage, they bash in the roof of the past and release its ghosts into the light.

__________________________________

The Northern Reach by W. S. Winslow is available now via Flatiron Books.

W.S. Winslow

W.S. Winslow was born and raised in Maine but spent most of her working life in San Francisco and New York in corporate communications and marketing. A ninth-generation Mainer, she now spends most of the year in a small town Downeast. She holds bachelor's and master's degrees in French from the University of Maine, and an MFA from NYU. Her fiction has been published in Yemassee Journal and Bird's Thumb. The Northern Reach is her first novel.