Danny Trejo on Doing Time with Charles Manson and Finding Freedom in the Boxing Room

One of America’s Great Character Actors Looks Back at His Time in Prison

I had boxed in every institution I had ever been in, from juvie to Jamestown, so by the time I got to San Quentin I had a reputation, especially among the Mexicans. The word was, “Oh, fuck yeah! We got a champ.”

They had fights every month, so I started training in the gym, where they had a ring and heavy bags. The guards took notice of me, and then I had status and privileges. They let the fighters go to breakfast early so we could head out to do roadwork on the track.

There were plenty of fighters who had no formal training. I could tell just by talking to someone how he’d be in the ring. How confident he was, how he held his body, if he got heated easily, all these things told me how knowledgeable he was about fighting. I put this knowledge to use on the streets, too. If I got into an argument with someone, I could tell if he could fight just by how he stood. Depending on how he was standing, I knew which arm he’d use to throw a punch and whether he’d be off-balance or not. If his legs were squared up with his shoulders, he was telling me he was going to fall. I knew how to read bodies and body language. I knew what to do and how fast I could do it because I’d done it so many times that it was a reflex.

Some guys did their time reading, playing chess, running the track, or playing pinochle. Each of these was an escape to another world—there were four guys at SQ who would play pinochle for a whole day, then leave the cards so they could return to them the next. The guys who didn’t have something like that went crazy. For me, it was boxing. Whenever I was boxing, I wasn’t in the penitentiary. My mind was in another world. And it did more than pass the time. Like the firefighting I’d done in juvie and afterward at the adult Conservation Camps, it felt important.

My first competition was a title fight. Even in the joint, when they announced my name, I felt like I was a star. Everyone would be bonaroo—all decked out—like it was a fight in Vegas. After all the roadwork, all the sparring, I was excited. I knew I was going to show everyone in that penitentiary just what I could do. When you know you’ve put in the work, when you know you did three miles of track work instead of two, you are filled with confidence. Every time I stepped in a ring I was representing my people, and I was going to make them proud.

As far as the prison system was concerned, what I had become was an “Institutional Convenience,” which meant “Do whatever the hell you want with him because he’s too much trouble.”

When I climbed into the ring, it was electric. Everybody was cheering like I was a celebrity. They knew who I was. They were expecting something, and I was going to deliver.

The only fight I ever lost was back in Jamestown, and it was because I threw it. I didn’t have any money on my books when I got there, and I needed it. Chino Sainz came up to me and said, “We have this fight for you.”

I’d just arrived, but I was Gilbert’s nephew, so everyone already knew I could fight. I didn’t have time to put in proper training, so I said, “Put some money on the other guy.” Everyone who knew me put money on him, I made a cut, and we all did pretty well that day. After that I became champion of Jamestown and never lost again.

A fight in San Quentin was a war. The gym was in an enormous metal-and-cement warehouse—it could fit most of the prison population. It was the 60s, and the race wars and the gang wars were heating up. The boxing matches were a way of establishing and claiming racial superiority in the joint. But even when I was fighting another Mexican, the Syndicate bet on me because they knew I wasn’t going to lose.

The inmates sat on chairs that were all locked together so they couldn’t pick them up if a fight broke out, but there actually weren’t many riots at the events. We segregated ourselves to keep the peace because we knew if we fucked up they’d take boxing away from us, and nobody wanted that.

The guy I was fighting was a roundhouse slugger, so I just got him with jabs, jabs, jabs. Maybe he could fight on the streets, but in a ring, he wasn’t shit. I smoked him.

Moments like that, my life in prison felt just as full as it ever had on the outside. But then there were moments when I feared prison was turning me into someone I didn’t recognize. Playing dominoes at a table on the Main Yard, I had picked four fives. In dominoes, that’s like getting a royal flush in poker. Even better, there was big money on the table. I couldn’t wait to play them. It was a Black guy’s turn. Only when heavy gambling was going down would whites, Blacks, and Mexicans play against each other. This guy was thinking too long, but I kept my cool because I knew I was about to blow everyone’s mind with what I had in my hand. A lot of money was flowing. The man finally moved, and it was my time to hit it. More money came onto the table. I didn’t notice a dude roll up because there were so many people watching. Then: bam bam bam bam. The dude hit a man who was leaning over the table next to the Black guy three times in the back and once in the neck. He must have severed a major artery because blood was squirting everywhere. I instinctively covered my face and got blood on my sleeve and hand.

Ty grabbed me. “What you doing, carnal? We’ve got to step.”

I held up the dominoes. “No, no! Keep playing!”

“Who gives a fuck?”

“I have a run of fives.”

Ty wasn’t impressed. “We got to go.”

I moved with everyone else. We had to get inside before they shut down the Yard and we were all stuck outside. When I got back to my cell, I was in a rage. I was holding on to the blood-soaked dominoes so hard they almost cut my hand. I thought, What kind of animal have I become? What kind of animal have I become?

Prison gang life eluded Charles Manson, and even if he could have fallen into it, he sure as shit wouldn’t have been a leader.

As far as the prison system was concerned, what I had become was an “Institutional Convenience,” which meant “Do whatever the hell you want with him because he’s too much trouble.” While some of the guards liked me because I was a boxer and ran protection rackets, I was simply doing too much business far too often for the authorities to continue to look the other way. The fact that I handled the heroin bag for Richard was common knowledge and something any one of a number of snitches might have told the guards. Another factor was race. Whenever a group of guys got too organized, the bulls would ship them off to other institutions.

Whatever the reason, I was sent off to Folsom. The ink on my tattoo—a huge, hot charra in a sombrero sprawled across my chest—was barely dry. Charras are the Mexican women who fought with Pancho Villa. They carried rifles and dynamite; they fought alongside the men. Mine was inked by Harry “Super Jew” Ross, a bad motherfucker from my hometown of Pacoima, who became a world-famous tattoo artist later in life. Mine was his first. Harry had started it in Susanville back in ’65. I went big because I thought I was in for ten years. If I’d known it was only going to be four, maybe I would have gotten something less massive, like a puppy.

Other guys were getting tattoos of Aztec warriors, but I didn’t want a dude. Harry used three E guitar strings run through a melted-down toothbrush, dipping them in India ink or melted-down chess pieces. He did the outline in Susanville, but after that I cut that dude’s face in Magalia and got shipped off to San Quentin. When Harry got to San Quentin, he did the shading, but then I went to Folsom. Harry said, “Don’t touch your tattoo—wait till I get there.” Harry showed up at Folsom and had nearly finished shading it on the Yard when I got sent to Soledad.

*

1968

Prison is a waste of the best years in a person’s life, but when I arrived in Soledad I wasn’t there to do my time and get home. Since I assumed I’d always be there, I treated it like my job.

I was resourceful, and resources in prison are traded in different currencies—food, drugs, whatever.

Back in ’61 in LA County I saw the “whatever” of this stretched beyond belief. By then every type of lockup was home to me. I’d been locked up so many times, I was more used to being inside than out. While I was waiting to get shipped out to Tracy, there was a greasy, dirty, scrawny white boy in County. He was so poor, he didn’t have a belt, and instead used a piece of string to keep his pants up.

The dude was going to get jumped by the Blacks, so he came to us for protection. The problem was he didn’t have any money. I felt sorry for him. It was clear the only shower the man was ever going to have was the one he was going to get in jail. There were three in our cell—Johnny Ronnie, Tacho, and me—so we told the dude he could clean up for us and we’d keep an eye out for him. He couldn’t sleep in our cell, but we let him sleep just outside so people knew he had eyes on him.

Even before I fake-fixed, I could taste it in my mouth. Any junkie knows what that is like. By the time he described it hitting my bloodstream, I felt the warmth flowing through my body.

A couple of days later the guy told me he had hypnotic powers and he could get us high. We weren’t doing anything, so we said, “Why not give it a shot?”

It was like a guided meditation. He talked us through the whole thing, rolling a joint, sparking it up, taking a deep hit, and the three of us felt super high. The man said, “Your body already remembers. It knows what to do. It anticipates getting high, and that’s how it works.”

That got my wheels turning. The next day I said to the dude, “If you can do that for weed, can you get us high on heroin?”

He said he could, but we’d have to really focus for it to work. I grabbed Tacho and Johnny Ronnie, and the dude sat us down and told us to close our eyes. For fifteen minutes, in great detail, he walked us through the process of copping the dope, finding a place to fix, cooking the heroin in a spoon, drawing it into a needle, and sticking it in our veins.

Even before I fake-fixed, I could taste it in my mouth. Any junkie knows what that is like. By the time he described it hitting my bloodstream, I felt the warmth flowing through my body.

If that white boy wasn’t a career criminal, he could have been a professional hypnotist, someone who went to high schools and state fairs and got people to come onstage and act like cats and stuff.

But he was, in fact, a career criminal. He was Charles Manson.

Inside, Manson worked alone. The elaborately constructed social structure we Mexicans had was something denied him, even by his fellow white prisoners. Men fight to the death in prison over the gang they’re in, but the different ethnic groups also cooperate with each other more than people think. It’s the way we keep order. If someone fucks up and owes a debt or fucks with people and causes problems, it is up to their gang to regulate them. Prison gang life eluded Charles Manson, and even if he could have fallen into it, he sure as shit wouldn’t have been a leader. It was only after he got out that he was able to create the social structure he wanted by finding a bunch of lost hippies in Haight-Ashbury and making them into a “Family.” If Manson had tried to pull his game in East LA, he’d never have been at the helm of shit.

_________________________________

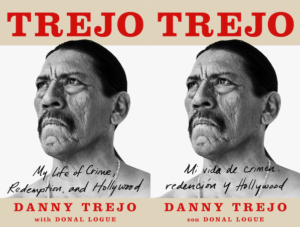

From Trejo, by Danny Trejo, with Donal Logue. Courtesy Atria Books, copyright 2021, Danny Trejo. The Spanish edition can be found here.

Danny Trejo with Donal Logue

Danny Trejo is one of Hollywood’s most recognizable, prolific, and beloved character actors. Famed for his ultra-baddie roles in series like AMC’s Breaking Bad, FX’s Sons of Anarchy, and director Robert Rodriguez’s global, billion-dollar Spy Kids and Machete film franchises, Danny is also a successful restaurateur. He owns seven locations of Trejo’s Tacos, Trejo’s Cantina, and Trejo’s Coffee & Donuts in the Los Angeles area, and is expanding his Trejo’s Tacos franchise nationwide. Visit DannyTrejo.com to learn more.