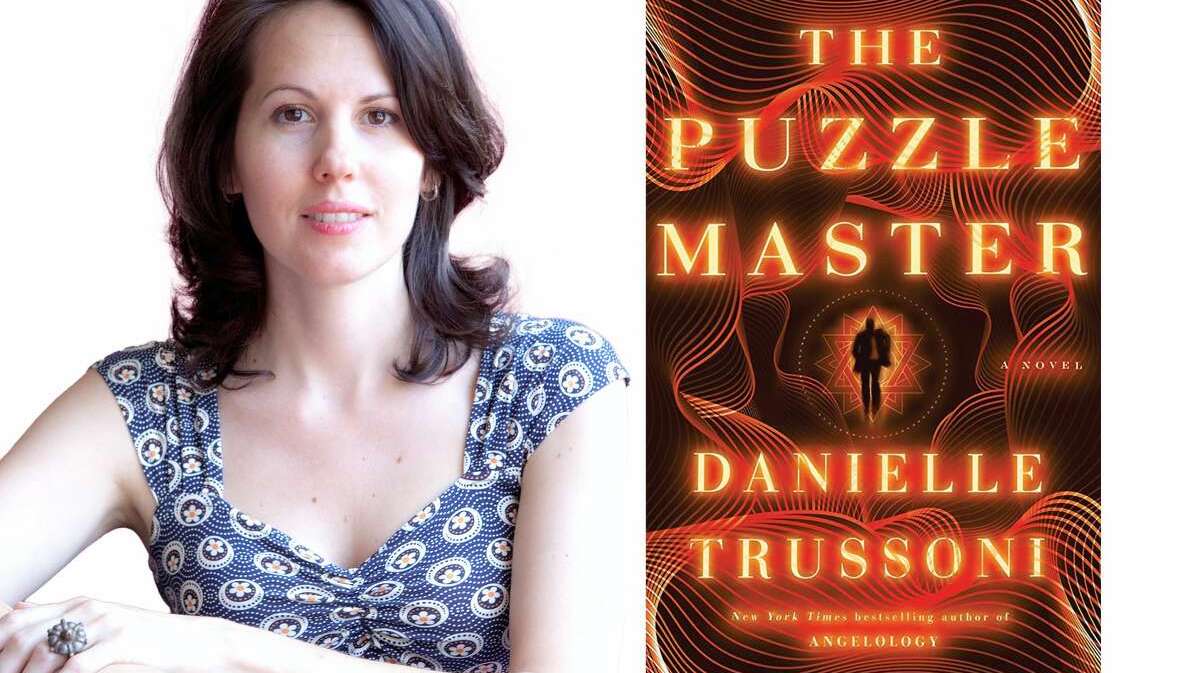

Danielle Trussoni on Pursuing Perfection, Draft After Draft

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of The Puzzle Master

Danielle Trussoni’s Angelology was a spellbinding quest novel that traced a clash between the dark angels, the Nephilim, and the forces for good, the Angelologists, from 925 A.D. in Thrace to New York in December 1999. At its heart is the search for the ancient, possibly dangerous lyre that lies at the bottom of the Devil’s Throat cavern in the Rhodope Mountains in Bulgaria. In its sequel, Angelopolis, and also The Ancestor, which was inspired in part by Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, she continued her innovative neo-Gothic path

Her latest, which will fascinate fans of Wordle, revolves around Mike Brink, a genius puzzle maker whose exceedingly rare “savant syndrome” puts him at the center of a search for the answers to a murder in upstate New York as well as a complex ancient religious mystery. In the course of our email exchange, I learned that Trussoni is a perfectionist, constantly revising, making changes all the way up to the finely polished end.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How was the writing, editing, launch of The Puzzle Master affected by the pandemic? How has your life and work gone during this time of turmoil and uncertainty?

Danielle Trussoni: I began writing The Puzzle Master during the pandemic. I was living in New York, and everything had shut down. I had a two-year-old who couldn’t go to day care, and so my husband and I were taking turns with her while the other worked.

As you can imagine, it was a mind-blowingly stressful period.

What gave me solace was writing. I began this book and the characters and plot were so magnetic and intriguing, and the research so much fun, that it really pulled me through. I also was really into puzzles during that time, especially crosswords and Wordle.

JC: Who is the inspiration for your puzzle master, 32-year-old Mike Brink, who, you write, was christened “the most talented puzzleist in the world” by Time magazine. Longtime New York Times puzzle editor Will Shortz?

How can the brain be damaged, and it opens one up to knowing something they didn’t know before?

DT: Mike Brink, the hero of The Puzzle Master, is a character who suffers from something called savant syndrome. He was a normal guy until, at seventeen, a traumatic brain injury left him with an almost miraculous ability to solve puzzles, solve impossible mathematical equations, recite Pi places into the tens of thousands, and remember everything he’s ever read.

Will Shortz is not the inspiration for Mike Brink, although I did meet Will Shortz after I had written a draft of the book. He gave me invaluable information about his life and allowed me to visit his home to see his puzzle library, which helped me imagine Mike Brink’s way of seeing the world, which is so very different from how I see things.

My character was inspired less by an actual person, and more by my fascination with savant syndrome, and what it says about the human brain. If an injury to the left hemisphere can open up abilities that we didn’t know existed, what does it say about consciousness? That question was a serious one enough to investigate in a novel, and I’m still wildly fascinated by the subject.

JC: And the dog named Conundrum?

DT: Mike Brink’s sidekick is a dachshund called, as you said Conundrum. I had a dachshund as a child that I loved, and I’ve always longed to have another one. Maybe someday. In the meantime, I’m having a great time writing about Conundrum.

JC: Your narrative begins with a confession dated December 24, 1909, Paris, begging forgiveness for “causing much sorrow” and lifting “the veil between the human and the Divine and staring directly into the eyes of God.” What prompted this mysterious passage. Did you always intend to put it at the beginning?

DT: The mysterious passage you mention is an excerpt from a series of letters that delves into the puzzle at the center of the novel—The God Puzzle. That section of the book brings us back to Prague in the nineteenth century and traces the origin of the religious mystery that the book explores. In the present-day story, Mike Brink is trying to solve this mystery, but it all began a long time ago.

I don’t want to give too much away about the nature of the puzzle, but I will say the puzzle was inspired by the work of a thirteenth-century mystic named Abraham Abulafia, and his fascinating and complex prayer circles. Those prayer circles can be viewed at the British Library site.

Here’s a link to them.

JC: You jump to June 2022, as Mike Brink drives upstate to Ray Brook, to a minimum- security women’s prison, to visit the head psychologist, Dr. Thessaly Moses, to discuss Jess Price, a woman convicted of murder in a case Brink recognizes five years before. The link? Jess Price, a young writer who has been virtually mute since her trial, has drawn a “peculiar” puzzle. It’s a stretch to imagine a puzzle maker being called in this way. What did you do to make it seem realistic and authentic?

DT: First of all, he was called in because Jess Price specifically asked for him to be called in. She wrote his name on the back of the puzzle she’s drawn. Her therapist, doctor Thessaly Moses, finds his name and calls Mike Brink.

The other element of this, is that Mike Brink is something of a celebrity. He’s been named by Time Magazine as one of the most talented puzzlists in the world. He was on the Colbert report talking about puzzle boxes, one of his favorite kinds of mechanical puzzles. So he’s very much in the culture. People know who he is. And so it’s not surprising that he would be called in to solve a perplexing puzzle.

JC: Mike Brink’s genius comes from an unexpected source. When he was a promising high school quarterback in a key game he ran the ball, only to be tackled, suffering a concussion that altered his perceptions forever. His brain injury led to “an extremely rare condition called sudden acquired savant syndrome.” Fortunately for Mike Brink, he has a doctor who trains him to thrive in his “new reality.” Where did you come up with the idea of a character with this “superpower?”

DT: This character began as just someone who was good at solving puzzles and had an uncanny ability to remember things. He didn’t have, as you say, a superpower. But as I went deeper into thinking about him, and as I revised my novel (which I do about twenty times, by the way) I became interested in the idea of genius, and savants in particular.

I realized that it would be extraordinarily useful (narratively) to have a hero who could solve complex mysteries, whether they be puzzles, math equations, or a historical religious mystery, as is the case in my novel. And it would be such fun to follow that kind of character. And so I began poking around looking for cases with people who fit that description.

When I stumbled upon sudden acquired savant syndrome, a disorder that is documented in about fifty people in the world, I was completely shocked and surprised that this actually exists. I mean: how can the brain be damaged, and it opens one up to knowing something they didn’t know before? It is a human mystery, one that I needed to explore.

JC: What sort of research was involved in creating/creating the puzzles that create a narrative thread in this novel? From the Lo Shu Square to Wordle to the God Puzzle to Jess Price’s puzzles to Mike Brink’s own puzzles to ancient codes used to communicate information about the Creator, including the I Ching and the Kabbalah. What role did World Puzzle Champion Wei-Hwa Huang play? And Brendan Emmett Quigley, NY Times Puzzle Constructor?

DT: The research was perhaps the most enjoyable part of writing this novel. I’m completely obsessed with the history of puzzles, the way that they’ve acted as both tools and traps for people throughout history. There’s an amazing book called Ancient Puzzles by Dominic Olivastro, and I used this as a resource throughout the writing of the book. I’m also interested in the history of religion, and how puzzles and mysteries feed into spirituality. All of these interests came together in this storyline.

The two puzzle constructors that you mention, Wei-Hwa Huang and Brendan Emmett Quigley, designed puzzles that appear in the book. Wei-Hwa Huang designed the Triangulum puzzle, and the number puzzles that are in the book and Brendan Emmett Quigley created the word puzzles throughout the book. I designed a few myself, notably the cipher that Jess Price gives Mike Brink at the beginning of the story—the one that has blots of blood over certain letters. But otherwise, I needed the help of professionals for the puzzles, which was wonderful because I was able to work on the biggest puzzle of all: the writing!

JC: The mistress of the Sedge House collects antique porcelain dolls, including a one-of-a-kind doll created by French master dollmaker LaMoriette, modeled after his beloved daughter Violaine. Jess Price finds Violaine, who then disappears. And, in a clever backstory, Mike Brink reads LaMoriette’s letters which describe his work with the porcelain-making Czech dollmaker, Johan Kral. In going back a century, Brink find clues to the mystery at hand. But you also end up giving a master class in the history, spiritual meaning and economic value of porcelain, especially porcelain dolls. How did it take you to learn all you needed to know for this element of the narrative?

DT: I spent months reading about this history of porcelain, porcelain dolls, and some of the more mystical theories about porcelain. There was one book that was extremely helpful when I was reading—The Arcanum by Janet Gleeson. It mapped out the place of porcelain in history, and especially as something coveted by alchemists.

Perhaps the most useful part of my research into porcelain were conversations I had with a porcelain scholar, Ann-Marie Richard, who sat down with me and talked me through the whole industry, from the manufacture of porcelain to the collectable nature of the dolls. It was fascinating.

JC: Part of the riddle of this novel is the way in which you connect the ancient codes with modern-day technology—in particular in villainous tech genius Jameson Sedge’s quest for immortality. Jameson Sedge, Aurora’s nephew, founded Singularity Technology to investigate his “belief that the human mind endures beyond the decay of the body.” Are there modern-day parallels to his quest among the tech founders?

It can be dangerous, too, getting so involved in the minutiae of a setting.

DT: There does seem to be an inclination to find ways to prolong life among people who have the most resources, and futurists are often very interested in technological ways to extend and enhance our biological capabilities. But I didn’t model Jameson Sedge on any one person. He is totally fictional.

JC: How did you build the settings like the Morgan Library, the Getty designed building at Bard College, Sedge House, “the kind of gabled and turreted estate you read about in a nineteenth-century novel,” where Jess Price encounters Aurora Sedge’s doll collection and the murder she’s accused of takes place, the synagogue in the Jewish Quarter in Prague where LaMoriette describes his first encounter with a golem?

DT: I went to every one of those locations you mention! I’ve always loved being in other cultures (I’ve lived in France, England, Japan, Bulgaria and Mexico). One of my favorite ways to get deeper into my setting is to go there.

For example, Sedge House is based on Wilderstern, a house in Clermont NY. I went on a tour of the house, and took photos of the room and modeled most of the scenes set in that house on a real room. I also visited The Morgan Library, and spoke to people about the history of the library and its holdings.

It can be dangerous, too, getting so involved in the minutiae of a setting, as I tend to write too much about the location, and it can bog down certain dramatic elements.

JC: Your Instagram posts make me curious about your process. You have posted manuscript pages from a novel written in hand. Do you always write first in hand? With colored pens? For The Puzzle Master, did you also create a puzzle that outlines the plot?

DT: I always write my first draft longhand, usually on legal pads. I love the freedom that writing this way gives me. I draw things in the margins; I cross out lines and write over them; I fold a page and tape it to another page (a kind of old-fashioned copy-paste).

I also just love the feel of a pen in my hand. I suspect this is because I began writing in notebooks when I was a kid, and it feels comfortable to me. And you’re right—I do love colored ink. I have a favorite fountain pen (a fine-nibbed Pelikan) and I change ink colors all the time

I haven’t yet mastered the art of the outline. I’m still hoping that will come to me one day, as it would save me a ton of time!

JC: What are you working on next? Another novel? Involving puzzles? A quest? Your recent Insta post mentions Kyoto?

DT: I am deep into the first draft of the next book in this series—The Puzzle Box which is (as you guessed!) set in Japan. It’s a continuation of The Puzzle Master, which has evolved into a series.

I went to Japan in April to visit the locations that are in the book—Tokyo, Kyoto, Hakone. The book revolves around a Japanese puzzle box, and a mysterious object that is locked inside. Mike Brink is brought to Japan to open the box and when he does… stay tuned!

__________________________________

The Puzzle Master by Danielle Trussoni is available from Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.