Daniel Torday on Why There Are No Acknowledgements in His Latest Novel

“That absence grows into not a void, but a validation of a privacy we’ve lost track of in our information-abundant existence.”

I kind of love acknowledgement pages. When I was trying to find an agent for my first novel, I would go to the local Borders (it was a lifetime ago) open to them often to discover which agents and editors novelists worked with, which MFA programs they’d attended, who their early readers were. My own first novel even had a plot point that surrounded a main character being acknowledged in the final pages of another character’s memoir.

I like all the back material in books—end notes, glossaries, histories of fonts and colophons—and I’ve found value and even joy in writing a couple pages of notes thanking friends, sources, editors, and loved ones for the help they lent along the way—because they did. They helped. Finishing a novel is less like winning an Olympic medal than it is like participating in one of those ancient Chinese landscape paintings where the grandfather started the painting on the left side of the canvas, and the grandson finished it all the way to the right. It is an art form that presents the accretion of work over time, and too often obscures the many people who ushered a book into existence behind a single authorial byline.

But as I was preparing the final copy for my fourth book, I found that much as I might have wanted to, I didn’t feel I could name the names of a number of sources from the early research that sent me to the page. While I’d heavily fictionalized the story I was telling, the novel is about an esoteric Jewish-Islamic mystical sect called the Dönme, followers of the teachings of the 17th-century false messiah Shebbtai Tzvi, more than 10,000 of whom still live and practice in Istanbul today. I’d begun writing at a moment of rising autocracy and fascism across the globe, and during my early months of reaching out to members of these communities in the US and in Istanbul, Turkey’s leader, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, was in the midst of an authoritarian crackdown on any dissent in his country.

Thousands of lawyers were sent to prison. The population of political prisoners exploded in the country’s jails. Turkish friends of mine here in Philadelphia made clear the danger: one friend’s brother was trying to get out, fearing for his life, to no avail. Merely getting on Zoom with members of what are known as a “secret Jewish” group in the country might put them in danger. Even close contact with some scholars and the secrets they’d unveiled, had on their desktops, could pose a material danger.

Whenever I grow worried we’ve forgotten why we need privacy to begin with: you don’t need it until you need it.

“But don’t you think there’s a good chance they’ll be fine?” I asked, naively.

“What is the benefit of the risk?” my friend answered.

I was writing fiction. I could fictionalize.

I would.

Relying on interviews I’d already conducted, and on reading, I discovered just how tenuous Dönme life could be if exposed. Even Turks who weren’t Dönme, but were publicly accused of being part of the sect, could have their public lives upended. Since the turn of the century, some of the bestselling books in Turkish culture have “purported to uncover the secret identity of the secular elite that has guided the nation for over a century,” according to scholar Mark David Baer. One book portraying Erdogan as a secret Jew, both in its pages and in a manipulated image on its cover, hit the top of the country’s bestseller list.

It’s hard to overstate the nefarious power of conspiracy theories over the idea that Muslims in the country are secretly Jewish; it’s especially hard when there’s a significant sect in the country of Jewish mystics who live outwardly as Muslims. As one major scholar, Cengiz Sisman, writes, “writing on the [Dönme’s] silence itself raises a moral dilemma about disclosing the society’s secrets.” It’s one I had to take seriously, even when imagining a fictional version of the sect here, in America, in rural central Ohio. Turkey holds no patent on the use of iterations of the “secret Jew” as an effective political smear; American Nazis before WWII called Roosevelt a secret Jew, referring to him as “Rosenfelt.”

So instead of thanking all those sources I’d hoped to thank by name, here’s what I wrote instead of a traditional acknowledgements page:

In this space, in normal times, I would go through and thank by name all the folks from the Jewish mystical sects depicted in this book who helped me during my years of research and writing. But these are not normal times. Autocratic rule in Turkey has placed members of the Dönme in Istanbul in more immediate danger than usual; simply accusing any Turkish official of being a “secret Jew” could put their public life into question. So here I’ll simply say: thank you so much to those who took the time, care and patience to talk with me, to read the sacred texts with me, and to help along the way. You know who you are.

Reading back over this note now, I’m reminded how painful—and jarring—it was to sit down and write a non-acknowledgements acknowledgments page. But it occurs to me that it also illuminates something about our historical moment. In a period when we’re all expected to self-promote, to keep a public ledger sheet of our accomplishments and our private lives, there’s a certain education in failing to do so for a good reason.

That absence grows into not a void, but a validation of a privacy we’ve lost track of in our information-abundant existence. Let the sources be the sources; let them do their private worship in private sanctity. Some exchanges of information are better unacknowledged. As I remind my students, and myself, whenever I grow worried we’ve forgotten why we need privacy to begin with: you don’t need it until you need it. You’d better hope it’s still there when the time comes.

__________________________________

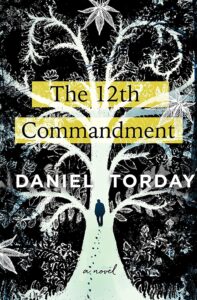

The 12th Commandment by Daniel Torday is available from St. Martin’s Press, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Daniel Torday

Daniel Torday is the author of The 12th Commandment, The Last Flight of Poxl West, and Boomer1. A two-time winner of the National Jewish Book Award for fiction and the Sami Rohr Choice Prize, Torday’s stories and essays have appeared in Tin House, The Paris Review, The Kenyon Review, and n+1, and have been honored by the Best American Short Stories and Best American Essays series. Torday is a Professor of Creative Writing at Bryn Mawr College.