My book Burn the Page is about both the importance of the stories we tell one another and the power in setting fire to the stories you don’t want to be in anymore, whether written by you or written about you by someone else. I’m writing it for the person I was in 2016 when I lived in a much different story than the one I’m in now.

Picture it: a five-foot-eleven, long-haired brunette metalhead trans lady reporter wearing a rainbow bandanna, an A-line skirt, and a black hoodie—okay, got that visual? Now she’s screaming obscenities behind the wheel of her four-door ‘92 Dodge Shadow America (…in 2016). She’s just shy of her thirty-second birthday; she’s 1.5 years into her first-ever long-term relationship and she has a negative net worth of tens of thousands of dollars after paying off her college loans. As usual, she’s half an hour late to her weekend job at a kebab shop, thanks to an insane commute in her $324 rust bucket, which has been painted primer blue—as in, primer and blue.

Her job involves delivering food, plus some washing of trays, the occasional cutting of baklava, the placing of drinks in the slide-door fridge, and the ladling of tzatziki sauce into tiny to-go cups. The only thing going right in her life at the moment is the state of her calves, which look amazing after sprinting up and down every apartment staircase in Arlington.

This woman is lonely as hell. As she shuffles into the kebab shop kitchen, she mumbles “Hi, hi, hi” to all of her coworkers, then barely speaks to anyone again for ten or eleven hours, instead staring at the walls between tasks—she can’t afford a smartphone to distract her, let alone health insurance, and the weight of those facts keeps her mind busy in the silence. Her coworkers would be shocked to learn that she’s an extrovert. In fact, they would be surprised to learn that she even likes people at all. She doesn’t mean to be a predictably ironic lady dick to anyone; she just has no idea how the $5 hourly pre-tip wage she’s ended up making at thirty‑one is somehow lower than the $5.15 an hour she pulled in at fifteen.

By this point in her life, this woman has also logged ten years of experience and thousands of bylines as a local reporter. She has interviewed the last six governors of Virginia multiple times each. She’s on a first-name basis with U.S. senator Tim Kaine, who at the time was running for vice president. But she’s been laid off twice in two years—first from covering state and federal political campaigns for The Hotline (often referred to as the “Bible of American politics,” which aggregates news clips about candidates running for office and features original reporting in the morning, afternoon, and evening news releases) and then from Yoga Alliance (a nonprofit dedicated to credentialing registered yoga teachers).

By mid-2016, she has been on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for 2.5 years, and while her physical appearance is aligning more with where she wants to be, it seems employers may think otherwise—she has sent out application after application for a real job with benefits, but no one is biting.

Life can change in an instant, even if said instant involves no material transformation, no births or deaths or sudden financial windfalls.

She’s tried the entrepreneur thing by opening a mobile yoga studio that plays heavy metal. It went belly-up within months of her selling out the first two classes, though the sight of a bunch of people in black hoodies stretching out into downward-facing dog to the soundtrack of The Pursuit of Vikings by the Swedish metal band Amon Amarth made those months so worth it. It turns out she has a lot to learn. Even a nonprofit transgender‑rights organization in need of a storyteller recently passed her over—a transgender storyteller—for another transgender storyteller with flashier credentials. That’s a pretty special level of fail, if you think about it.

So the Afghan Kabob House it is: a job where she spends more money than she makes, thanks to the endless car repairs, but one where the boss hired her after two interview questions—“You speak fluent English? That’s good. Can you start Monday?” She’s got this gig and one other: a part-time reporting job for a local paper in Rockville, Maryland, offered by an editor who told her during the interview, “Why the fuck would you want to work here? This job pays for shit.” She works seven days a week and has missed out on five months worth of weekends with her partner and stepdaughter, because that’s what happens when you’re a “lazy millennial” with a B.A. working two jobs without benefits.

This woman has dreamed of ditching it all to become a full-time touring musician—but that dream is on its last legs, too. She’s been a fixture on the local metal scene for a long time, but transitioning as a live musician hasn’t just been scary—it has involved her trying to figure out on-the-fly who she is onstage. Usually, metal chicks work that out as goth teenagers, but when you’re in your early thirties, you can only slather on so much fake-tortured eyeliner before it creeps its way into your crow’s-feet.

Her friends have all been cool with her transition, but now that her voice isn’t holding up live—in fact, it’s become more and more timid—she finds herself losing confidence. Meanwhile, her band hasn’t been practicing much, and the gigs are few and far between since both Jaxx and Ball’s Bluff Tavern—two staples of the Northern Virginia metal scene—closed. The dream isn’t just slipping; it’s on a glide path out the door.

On top of it all, this woman happens to live in a country where Donald Trump is about to accept the Republican presidential nomination, and forty-nine LGBTQ people and their allies have just been shot to death at Pulse nightclub in Orlando. The morning after the Pulse shooting, she drove, completely dazed, around Arlington and Georgetown, sobbing her way through deliveries as NPR reported a seemingly endless increasing body count, fighting to maintain a stoic face every time she handed a plastic bag of lamb and lentils to someone whose rent for their two-bedroom apartment cost far more than she would make that month.

This poor woman is crying—a lot. And not just because the terrible shift in the political climate feels unstoppable. She lives in Virginia, where at the start of the 2016 Virginia General Assembly session, a few months before she started the kebab job, Republican state delegates filed nine anti-LGBTQ bills—the most in any state legislature in the country. She’s been trying to assume a more activist role in her community, carving out a few mornings a week to go down to Richmond and talk to legislators about voting against these awful bills. Despite her efforts, she’s feeling pretty pessimistic.

While in Richmond, she doesn’t even bother talking with her own state legislator. He’s a right-wing fixture as permanent as the Lost Cause Confederate statues in her hometown. This man, Bob Marshall, was first elected to office in 1991, when she was seven years old. During her first year as a working journalist in 2006, he proudly declared to The Washington Post that he was Virginia’s “chief homophobe.” That same year, he authored a state constitutional amendment to ban all legal recognition of same-sex couples, and Virginia voters approved it, passing it by 13 percentage points.

Ten years later, the man hasn’t shifted course at all. He’s authored two of the nine anti-LGBTQ bills she’s protesting. Every January, as Marshall and the rest of the state legislature converge on Richmond for the opening session, she asks herself, “Which of my civil rights am I going to lose this year?”

What this sad-ass woman doesn’t realize, though, is that today, August 4, 2016, when she gets home from work, she’s going to get an email. This email will impart a lesson she’ll never forget: Life can change in an instant, even if said instant involves no material transformation, no births or deaths or sudden financial windfalls.

Instead, what it does is shift this woman’s self-perception—the way she’s been connecting the dots of her life into a bigger story. A new picture emerges in her mind: She’s no longer Danica the inadequate failure, Danica the dead end. Instead, she’s standing at a turning point: the moment when her story becomes the origin story I now recognize as my own.

The email is from Don Shaw, the Democratic nominee who ran against Bob Marshall in 2015 and abandoned a plan to run a second time in 2017. By that point, we had met many times over the course of my recent activism work. His email is short and poses a quick question: “You live in the 13th—have you given any thought to running against Marshall? You’d make a fantastic candidate! ;-)”

My inner Ralph Wiggum is the first to react: “Me run for office? That’s unpossible!” I stare blankly at the screen for a bit, say “Huh!” and walk away from my laptop and the open email.

I am living proof of what can happen when you discover that your story doesn’t have to be what you thought it was.

That little “huh” follows me around the rest of that Thursday night, floating about me like an ember. When I climb into bed and try to go to sleep, the ember drifts down and sets my sheets on fire. The following afternoon, when I get a follow-up call from Rip Sullivan, recruiting chairman of the House Democratic Caucus, I grin around the big bags under my eyes. I’ll need a couple of months to wind down my work at the newspaper and the restaurant and I’ll need to get trained, but if everything works out by December, then I’ll do it. I’ll take on Bob Marshall. I’ll find a way to win.

*

Go figure: On November 5, 2019, a little more than three years from my dark nights at the kebab house, I was reelected to Virginia’s House of Delegates, proving that my 2017 victory over Bob Marshall was more than a fluke. Since I took office, I’ve helped bring health insurance to 600,000 Virginians—and counting—who didn’t have it before. I helped the Democratic Party take back not just the House of Delegates but total control of the Virginia government for the first time since 1993.

My colleagues and I, in our first year in the majority, voted for Virginia to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution of the United States after a nearly 100-year fight—one win of many during our two-year majority. On top of that—because every thirtysomething kebab delivery girl knows how this goes—in the past five years I’ve sung onstage with Arcade Fire’s Will Butler, received a congratulatory phone call from Joe Biden, promoted anti-bullying efforts with Demi Lovato at the American Music Awards, spoken at the 2020 Democratic National Convention, and starred in a Vice news documentary about winning grassroots elections.

Oh, and the Westboro Baptist Church (WBC), of “God hates fags!” fame, protested my existence as a trans woman in the legislature in Richmond, which led Randy Blythe, vocalist of the quite appropriately named metal band Lamb of God, to lead a two-hundred-person-strong counterparty that drowned out WBC’s worst for half an hour with… kazoos.

Governor Ralph Northam signed 23 of my bills into law during my first two terms; we passed the largest transportation funding bill since 1986 and raised teacher pay; and my 2017 victory inspired trans folks across the country to run for office, increasing our number of out-and-seated transgender state legislators from one in 2018 to four in 2019 to eight in 2021, including the first trans state senator, Sarah McBride of Delaware. I even earned a third term!

Life can change in an instant. It can change in an instant. I am living proof of what can happen when you discover that your story doesn’t have to be what you thought it was. Reality doesn’t have to follow the pacing and predictability of fiction, and neither do you.

__________________________________

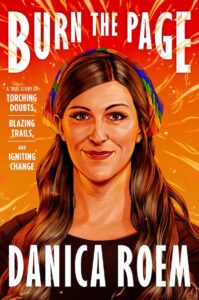

Excerpted from Burn the Page: A True Story of Torching Doubts, Blazing Trails, and Igniting Change by Danica Roem, published by Viking.

Danica Roem

Delegate Danica Roem, part of the historic group that flipped Republican seats in the 2017 election, is the first out-and-seated transgender state legislator in American history. Prior to her political career, Roem was a journalist and now serves as a frequent guest on national media. She and her work have been featured in USA Today, People, GQ,The New York Times, Elle, and many others, and was the subject of the GLAAD award-winning documentary This Is How We Win.