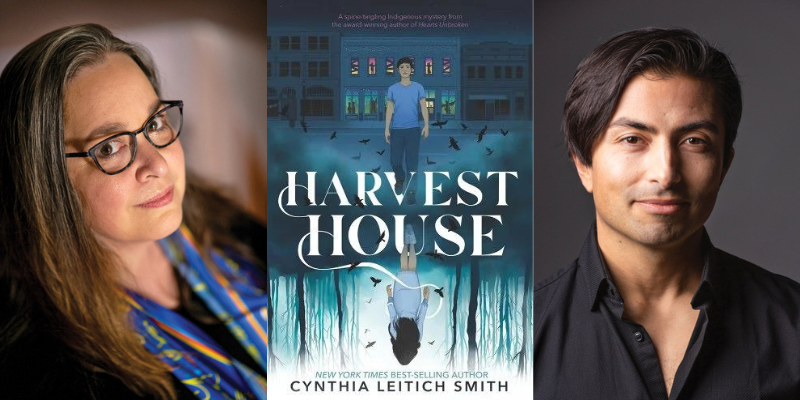

Cynthia Leitich Smith and Shaun Taylor-Corbett on Audiobook Collaboration

In conversation with Jo Reed on Behind the Mic

In today’s bonus edition of Behind the Mic, host Jo Reed welcomes author Cynthia Leitich Smith and narrator Shaun Taylor-Corbett for a lively conversation about making memorable audiobooks for children and young adults. Cynthia Leitich Smith (Muscogee citizen) is a highly acclaimed author for young readers and curator for Heartdrum, a Native American-focused imprint from HarperCollins. Shaun Taylor-Corbett (Blackfeet) is a frequent narrator of audiobooks from Heartdrum, including Cynthia’s most recent, Harvest House. Listen in to hear Cynthia and Shaun talk about the audiobooks they’ve collaborated on and the importance of showing true representation of Native kids and teens in books and audiobooks.

Read reviews of Cynthia Leitich Smith’s audiobooks and find more audiobooks narrated by Shaun Taylor-Corbett as well at AudioFile.

*

From the episode:

Jo Reed: Cynthia, do you mind talking about the origin story of Harvest House, an audiobook that you wrote and that Shaun narrated?

Cynthia Leitich Smith: Harvest House has sometimes been called a Native American “Scooby-Doo” because it centers on a group of teenagers who naturally have a large, bountiful dog, but it also touches on more serious themes. The origin story is rooted in a fun time, a night in which my cousin and I took our mothers to a commercial haunted house in Kansas City. A sort of Halloween fun house, the kind of place that you would go for a spooky but safe good time, and as a writer, it had stuck out in my mind—the “what if.” The what if being, what if you went to one of these make-believe haunted houses and it turned out it was really haunted?

At the same time, I was pondering whether—and if so, how—to address some of the misrepresentations of Native people, especially with regard to the horror or gothic fantasy tradition. All of those very disturbing stories of so-called Indian graveyards and Hollywood sort of run amok, and at the same time, the very real crisis around missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and our two-spirit relatives. So all of those different threads came together in a way that I hope is a story that is both a page-turner for young readers, shows the full breadth of daily life, and balances a bit of spookiness with more serious real-world themes that young people can carry forward in a way that is more knowledgeable and aware.

JR: I think it’s also so important that Harvest House also centers on a first love, a really strong family, and a vibrant extended community. It’s so textured, I think, as a book.

CLS: Thank you for saying that. It’s always been important to me not to ignore the challenges that our Native teens face, but, at the same time, none of us are defined by the hardest parts of our lives. And showing true representation of Native teens on the page means showing them in the full breadth of their humanity—a full range of emotion and life experience, some of which are universal, some of which are tender, and certainly many of which are joyful. While there are families that have challenges, there are also those that are very healthy and functioning at the level that we would hope they would for their young people.

JR: Shaun, you receive a book like Harvest House to narrate. What’s your process? How do you prepare when you’re handed a book for young adults?

Shaun Taylor-Corbett: I just think this book is so brilliant. I read it through just as a fan of Cynthia’s writing and work, and I let myself be affected by it as a reader first. And as I go along, because I’m an actor, I have voices that pop up in my head or something that connects me to them. And I start to record each voice as I’m reading, or something, initially that speaks to me about the character, different characteristics, all the relationships. I approach it like approaching a great film or play and how I would want to portray these characters or see them with all the intentions of the author. And it’s a big responsibility for me, especially being Indigenous, and mixed race, and having grown up very confused with some of the things some of these kids in the book have to face in our society with different stereotypes, and also, like you’re both referring to, just having a really rich layer of experiences being young and not just being defined by one thing, and how to balance all those things. I think what really spoke to me were the relationships, but then also interacting with people who viewed me a certain way, and not having the tools as a young person to respond to some of the stereotypes that other people have about Native Americans.

I didn’t have books like this. So, reading this book, I was blown away by what a young audience will be able to get from this, and I think you do actually learn from this, how to approach other people in talking about it and how to approach adults. But it’s also just a great, exciting story that pulls you in. It’s a page-turner with all the elements that you desire as a narrator, if you’ve done all the preparation, while you’re reading it you’re having the experience of it and all the emotions of it, and hopefully that comes across in the performance and what people hear.

JR: Cynthia, I wonder what responsibilities you might feel you have when you write for younger readers, whether YA or middle grade or picture books?

CLS: I’m very aware of how deeply young readers take in story. When I first got started, my focus was largely on being accurate, authentic, informative, and, above all else, entertaining. Because if they don’t want to turn the page, none of the rest of it is going to happen. And what I’ve found over some 25 years now as a published author from conversations with and letters from kids is that books can really open them up to be themselves. They can validate young readers; they can expose them to new interests that have a defining impact on their lives.

I’ve heard from kids with regard to Indian Shoes who are being raised by a grandparent. So they see themselves in that relationship between Ray and his Grampa Halfmoon, or they have a pet parrot, or they live in Chicago, or they’re baseball fans. Kids connect with books in a lot of different ways, but it can be profoundly validating to them and also an awakening.

When I was in Houston, I did a school visit, and it was a program centered on freeing the young writers’ voice, teaching them how to write stories of their own heart. And so I read just a couple of excerpts of some of my books as examples, and a little girl came up to me afterward and whispered that she was a citizen of Cherokee Nation. I’m Muscogee, and those are tribes that are very closely located to each other, that share a border. I also have Cherokee ancestors, even though I’m a Muscogee citizen. And she had family who lived next door, literally next door, to family of mine. She an out of the classroom, throwing her arms up in the air, yelling to all of her friends, “I am Cherokee,” in all of her nine-year-old-pride-voice. And the teacher turned to me and she said, “I had no idea. I assumed she was Latina.” I said, “You know, she could be both!” because so many of our kids are bicultural or from interracial families. A lot of times we fly under the radar, due to the myth of extinction and erasure because people aren’t expecting to see us there. They may see a kid who to them is coded white or Black or Latine and not realize that child is also Indigenous.

JF: Cynthia, Heartdrum is the HarperCollins imprint you curate that is devoted to books for young readers by Native American authors. Can you tell us the origin story of Heartdrum?

CLS: As you mentioned, Heartdrum is an Indigenous-focused imprint of HarperCollins Children’s Books. We publish books for all age levels of young readers, picture books, chapter books, middle grade, and YA. And for a long time in my career, the mere existence of something like that sounded like a dream too misty for me to even begin to aspire to. I thought if anyone would do it, anyone I would trust, it would be my original editor, Rosemary Brosnan at Harper. I reached out to her, and Rosemary wrote me back the next day, and said “I love this! I’ve talked to everyone at HarperCollins, let’s do it!” and I thought, what have we done! I was so excited, I was dancing around my condo, I cranked up Olivia Newton-John’s “Xanadu,” which is my go-to for music from the muses, and thought, okay, we have a clear shot. If we can pull this off, hopefully more publishers will look for Indigenous voices and visions and we could maybe get a foothold in some significant seismic change for the better in publishing, to serve the kids.

JR: Shaun, how do you see Indigenous narrators re-imagining books for younger listeners?

STC: Now so many of my artist friends who are Indigenous are narrating. It’s a beautiful thing to see because with each narrator there’s a world of history, background, knowledge from their particular community or tribe. And then there’s a community of people in different tribes with common stories and common history interacting with each other. And I always have a specific goal that more Blackfeet narrators and authors and storytellers can also find their way to this work for our community out there, because I see the impact of good art, especially stories, on a community, how uplifting it is. All my mentors and elders back home keep telling me that with each one of these beautiful books and stories they’re just so excited. So excited that these types of stories are more normalized.

_____________________

This episode of Behind the Mic is brought to you by Brilliance Publishing and BetterHelp.

To listen to the whole archive of Behind the Mic with AudioFile Magazine, subscribe and listen on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Google Podcasts, or wherever else you find your favorite podcasts.

Behind the Mic

Every Monday through Friday, AudioFile Editors recommend the best in audiobook listening. All in 6 minutes or less. It’s short, sweet, and just what your ears need.