Cutting Class: On the Myth of the Middle Class Writer

Alissa Quart Reckons With the Precarity of the Writing Life

The following is the first of a six-part collaboration with Dirt about “The Myth of the Middle Class” writer. Check back here throughout the week for more on the increasingly difficult prospect of making a living as a full-time writer, or subscribe to Dirt to get the series in your inbox.

_______________________

Darryl Lorenzo Wellington was for two years the sixth poet laureate of Santa Fe. He also sold his plasma to get by.

I first met Wellington through the organization I co-founded, Economic Hardship Reporting Project, when I edited an essay about how he sold his blood so he could continue to be a writer. In his last volume, Wellington describes his writing in much the same way he talks about the place he lives: full of “riddles, tiny insidious lights, mysterious UFOs and mirages that beckon me.”

One of the mirages that resides in many books today, of course, for him and for many of us, is the idea of its author being a “middle class writer.” That appellation seems somewhat fantastical, something borne of secret inheritances and side hustles. Becoming one has become the literary version of the illusory American Dream. It rhymes with the “do what you love” exhortation that was directed at my generation and those younger, a rallying cry for those born in the later 1970s and 80s, an ideology that mixed techno-hyper-individualism and hippie pleasure-seeking. Its proponents were up on the problems of workplace alienation and exploitation but rather than prescribing social change they merely proposed you get a cooler job.

The mandate to make a living pursuing one’s deepest aspirations drove scores of young people into the MFA programs and journalism schools that trained writers. They proliferated, from 79 creative writing programs in 1975 to the recent number of 602 undergrad and 247 post grad programs. This was fine until graduates wound up in debt—these degree programs cost so much—and then graduated into a brutal job market and a climate of stagnating wages at publications owned by billionaires and private equity firms. It turned out that labors of love also got caught in the maw of capitalism.

Even when he was the poet laureate and was often invited to speak, he made just $30,000 a year, a combination of the $10,000 honorarium from the city and speaking fees.

Conditions for writers and other creatives were already shaky, their personal finances in many cases unsustainable, before the COVID-19 pandemic. The way that Wellington, 59, sees it, the pandemic made “the borderline impossible, truly impossible.” Nevertheless, he says, “I still do it.” Doing it entails a recent essay anthology he has put together, including a piece on the economic perils of being a writer.

While he is widely published, Wellington has never earned enough to have a savings account. Even when he was the poet laureate and was often invited to speak, he made just $30,000 a year, a combination of the $10,000 honorarium from the city and speaking fees; in his home Santa Fe the median rent for a one-bedroom apartment was $1,996 in 2024, up 15 percent from the previous year.

But according to a 2022 Authors Guild survey of 5,699 published authors, Wellington was actually doing well financially, compared to the median American author. The median gross pre-tax income of full-time, established authors was $25,000 per year, only $10,000 of which was from book-related sources. In contrast, in 1989, the median author income was $23,000, not adjusted for inflation. Of the Authors Guild’s respondents, 56 percent said they made extra income from events, ghost writing, teaching, and yes, journalism. At the same time, the rental market has climbed to new heights.

“People hate how AI is going to destroy writers and artists,” Wellington says. “But rent increases are far more likely to.”

*

When I was growing up in the 1980s, I’d turn over my Vintage Contemporary edition of the latest Raymond Carver collection and stare at his author photo, black and white, leather jacket-clad. Within its pages, I found writing of a cool, melancholic precision describing failed American dreamers drifting through life. I loved that he was working class. Perhaps writers didn’t have to come from privilege, I realized, although troublingly, as I paid more attention, I saw that those poorer writers seemed to always be white.

The postwar creative program system can be read as an institutional reaction to the decline in the market viability of writing.

As the child of parents who taught at CUNY—my mother’s parents immigrants who owned a small shoe store in the Bronx—this was the kind of mobility I needed to believe in, this different version of “American opportunity.” The story went like this: if a person read and was original enough people would talk to her. Then, they might publish her and then she could even earn enough for her rent. She was, unfortunately, usually white for this equation to work. And this belief wasn’t just cultural brainwashing. The postwar creative program system can be read as an institutional reaction to the decline in the market viability of writing; academia was absorbing people who couldn’t get jobs, or it was expanding who could think of themselves as a trained writer.

As Mark McGurl, author of the key study of this, The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing, and a Stanford literature professor, put it to me, Carver and “lots of writers found their way to writing classes in the postwar period where they wrote about working, where that was the subject matter of literature—but that moment is gone.”

Today, there are a small number of fiction writers and poets who write explicitly about the experience of backbreaking or humiliating underpaid day jobs and the financial struggle that comes with them. Sometimes it’s nonfiction essayists like Wellington or Brendan Joyce, who has written a poetry collection called Unemployment Insurance and has worked as a busboy. It’s also poets from working-class backgrounds, who have written about their own housing insecurity or about labor organizing, like Jen Fitzgerald, author of Art of Work, and the poet Rodrigo Toscano: they both appear in our new anthology Going for Broke. Other recent examples are novelists, and novels, like Raven Leilani’s Luster or Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age.

Annie McClanahan, author of the book Dead Pledges: Debt, Crisis, and Twenty-First-Century Culture, about how the epidemic of American debt interlaces with popular culture, notes that Reid and Leilani “are doing the most interesting stuff right now with class and money and service work, and both have said that they are writing on the basis of their own experience, as a gig worker and as a nanny-babysitter, respectively.” Sometimes these books about social class reflect the writers’ early life penury, as in Andre Dubus III’s recent novel Such Kindness.

The more work provides actual meaning in people’s lives, the more it’s denigrated as hobby or vanity project.

All of these writers are examples, of course, that despite the wrong-headed and corrosive underpinnings of the “do what you love” ideology, writing books is great work if you can get it.

Unfortunately, fewer and fewer get the chance to translate the mindset into a reality. Instead, they marinate in an atmosphere of “cruel optimism,” as the scholar Lauren Berlant wrote in her book of the same name, an ambience that “exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing.” Professional possibilities have become more limited, wrote Berlant, including “upward mobility, job security, political and social equality, and lively, durable intimacy.” What today’s writers experience when they “do what they love” could be likened to Berlant’s “stupid optimism.”

It must be said, though, that the advice “do what you love” was and is usually meant kindly, as a way to correct the old ideas about labor as something that is dutiful or mechanical or lifeless. And “doing what you love” was more achievable in previous eras—at least for some slices of the population—when writing was a job and compensated accordingly. Today, however, writers are often encouraged to work for exposure, or to think of low pay and lack of job security as a supposedly fair exchange for not being bored out of our skulls—yet another hat trick of neoliberalism, where the more work provides actual meaning in people’s lives, the more it’s denigrated as hobby or vanity project, which makes it easier to keep labor costs down across the board.

Nevertheless, there are those who keep writing without the support of institutions or intergenerational wealth. There are those of us who keep trying to build up said institutions so they can do so, so it’s not only the rich writing about the poor to be consumed by the middle class.

To pay his rent, for example, Darryl Lorenzo Wellington has received small grants from media non-profits like ours and the Community Change; he has taught elementary school, given speeches about writing and race. Currently, he’s even paid to perform the role of the novelist Richard Wright, the author of the novel Native Son, on stage.

“They call that ‘creative entrepreneurship,’” Wellington says, emphasizing the phrase’s absurdity.

Yet for him, remaining a writer has always been crucial: “I wanted to do my thing, do something unique.”

And he has.

_______________________

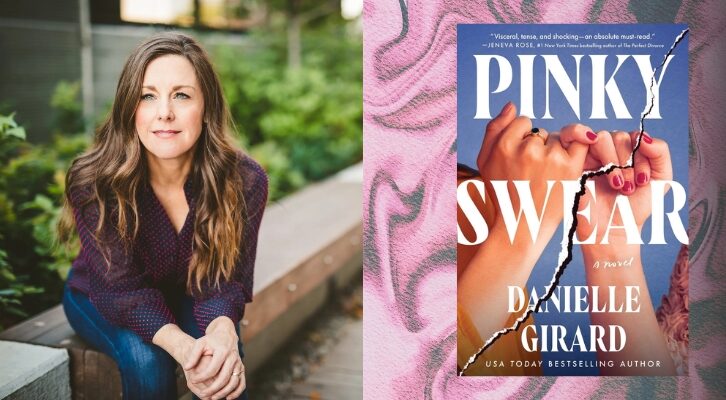

Illustration by Colleen Tighe

Alissa Quart

Alissa Quart is the author of five acclaimed books of nonfiction including Bootstrapped: Liberating Ourselves from the American Dream (Ecco, 2023, out now in paperback). They Are Squeezed, Republic of Outsiders, Hothouse Kids, and Branded. She is the Executive Director of the non-profit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. She is also the author of two books of poetry Thoughts and Prayers and Monetized. She has written for many publications including The Washington Post, The New York Times, and TIME. Her honors include an Emmy, an SPJ award and a Nieman fellowship. She lives with her family in Brooklyn.