My husband was right—we met in a café, where I worked at the time. The first time I laid eyes on him, he hadn’t seen me yet. His hair was lighter then, and he had more of it, long across his forehead. He was wearing a blue shirt, he seemed very solemn and kept looking around. He was with an older man, who I thought, correctly, was his father, and this man was counting out coins onto the table. In the years after, I grew to treasure the memory of that moment, of seeing my future before I knew what it was, seeing the pair of them before they were my husband and my father-in-law, when they were just two strangers. I swiftly made evaluations—they were not well off, they had to count their coins out for breakfast, they might be on holiday, or in the city for work—and they reminded me of my own family, whom I never thought of if I could help it. This filled me with both sentimentality and unease, set my heart’s scene, because sometimes we return to what we recognize, whether we want it or not.

The tablecloth was white but stained, and I had flipped it over when I laid the table so nobody would see the marks. I stalled; I had to go and take their order, but I was tired that day and didn’t feel like talking. Every day I went to work and wondered if it would be the day something or someone walked through the door and changed my life. It could be him, I thought from across the room as I worked up the energy, or maybe I only think that now, retrospectively, to give the memory gravitas. The floor was green linoleum, the menu was spread in front of him although he wasn’t reading it, the waiter drying dishes at the sink with a red cloth, though they were smeared and not properly clean, wiping them once, then again. But I did walk over in the end and ask them what they wanted, and he looked up at me and ordered a boiled egg and bread. Black coffee. I didn’t know that he would become something to me and that that something would change with time, would grow dearer and then less dear, less strange and then more so, the memory of the old affections jostling for space with the new hurts, incredible, recriminatory. The egg came peeled and he opened up his bread and with no self-consciousness put the egg on top, over-salted it, and mashed it very methodically with his fork, as if it was something he did every morning. I watched him do it as I took the order of another table. By the time he was satisfied enough to eat you could hardly tell what was egg and what was bread.

He came in the café again the next day without his father and sat at the same table. He was shy, he was from elsewhere, I liked his long tapping hands, I liked his light hair, I didn’t like that he had to count his coins, but he didn’t count them that day, so maybe I forgot. He just ordered coffee this time, one cup, then another, waiting to talk to me. And I felt more like talking that day, I had been thinking about the eviscerated egg and was disappointed when he didn’t order one, and he never ate one like that again, not to my knowledge, as if it was a rare treat or temporary affectation or both, though I waited, hopeful, every time.

On the cool blue morning after the party, I woke up with my husband, lay there with my eyes pressed shut. Let him suspect nothing, I thought. Let him suspect me marble-like as a corpse. He was buttoning his shirt. He made no noise beyond the exhalation of breath, no little utterances of frustration or song. With my eyes still shut I heard him fetch a glass of water. I could not hear the swallow of water catching in his throat but I could imagine his hand lifting the glass, clenching around it and then releasing, leaving it on the table for me, to wash up or to drink from too, which is what I did when I heard the door open then shut. It was hard to find the exact place on the glass where his lips had been, though I inspected the rim, I made my best guess and put my lips there too. I have always been a sort of archivist, glutting myself on what has been left behind.

I dressed quickly in the previous day’s clothes and made my way down to the dark street. My husband was ahead of me, and he suspected nothing. From a distance I appraised the way he moved when nobody else was around, but could detect no difference, no simmering sense of anger or of wonder or private joy. I was disappointed, but also I thought maybe I was too far away to see the signs, that there could still be some mystery there to excavate, if I only looked close enough. Was he feeling cheerful, or was it just the unthinking movement of his body? It was hard to know, it was a failure in me that I didn’t know. It felt good to name these shames, salving to admit them to myself. He disappeared into the bakery. I waited in the cold with my arms around myself.

When I was sure he was downstairs I walked through the side alley to the back, stepped around the bins to the low, narrow window which gave onto the cellar, and then on my hands and knees I got down into the dirt to see what my husband was doing. He was wet with sweat already, wearing one of his usual heavy linen shirts. I knew exactly the texture of these shirts and how they smelled pressed up to my face, how they felt when I was searching for some kind of evidence, the kind of evidence any wife would look for. I thought to myself how the worst I had done really was not any of the little betrayals but in murdering my marriage with familiarity, and it was unfair because that is only what marriage demands, the careful establishing of familiarity in order to be able to live your life the next day and the next and the next.

He shaped the dough and put it in the pans, efficient, balletic. It felt like I was watching something that should not be seen, but then there was nothing really to see. It was a disappointment and a relief. His hands worked smoothly and unthinkingly, he was unreadable, which maybe meant he was happy, that he wanted for nothing. And this made it worse, the idea that he wanted for nothing, and it was just me who was alone with my desire like a ragged hole in my chest. Watching him made me want him, watching him as another might see him, with his good strong arms and his hands that patted, shaped, stretched, his hands everywhere and easy, his hands not on me.

The things that keep us alive are not very often erotic, but it’s all right because there is so much left that is. The rising dough; the glimpses just out of sight promising something better, something yet to come. What if Violet could see me low to the ground, with the palms of my hands and my bare knees, my dress pulled up, filthy? She would nod with interest, I decided then. She would understand the desire to watch, to see, would not find me pathetic, even when I discovered that there was nothing for me there.

__________________________________

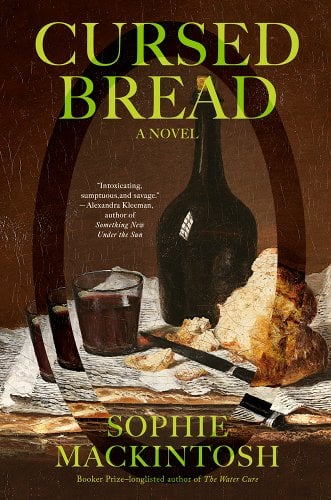

From the book Cursed Bread by Sophie Mackintosh. Copyright © 2023 by Sophie Mackintosh. Published by Doubleday Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House. All rights reserved.