Currybooks: On Authenticity and Our Expectations of South Asian Writers

Diasporic Writers Have to Play Both Tourist and Tour Guide

In a 1982 essay, Salman Rushdie describes several attempts at defining the “Indo-Anglian” writer, and indeed the idea of Indianness itself, that he encountered at a conference about Indian writing in the English language. The definitions on offer ranged from a knowledge of Sanskrit to membership in mainstream Indian culture, disregarding the minority cultures of Buddhists, Sikhs, or Muslims. Rushdie, himself a member of that latter group, recollects the point precisely: “If Muslims were ‘Mughals,’ then they were foreign invaders, and Indian Muslim culture was both imperialist and inauthentic. At the time we made light of the jibe, but it stayed with me, pricking at me like a thorn.”

The concept of the “Indian writer” (especially Indian writers abroad such as Rushdie) has since expanded into the idea of the “South Asian writer,” the author of “immigrant fiction”: The category has broadened, and the critical need to define brown writers in English by their exact place of physical and linguistic origin has lessened. Contrarily, the critical and popular discussion around what’s between the pages of one of their books is perhaps more narrowly definition-focused than ever: as the tropes and genre conventions around books by South Asian authors have accumulated over the decades since Rushdie’s essay, the expectations for what brown writers are supposed to do in their work have narrowed.

Hints and swipes aside, what differentiates the kind of work my younger, even more irritating, self called currybooks from the greater body of diasporic novels? For one, currybooks typically detail a wrenching sense of being in two worlds at once, torn between the traditions of the East and the liberating, if often unrewarding, freedoms of the West—as with, for example, V.V. Ganeshananthan’s 2008 Love Marriage, in which the Sri Lankan-American protagonist traces her ancestry and its impact on her present at the deathbed of her Tamil Tiger uncle. There’s typically also a generational divide, a bridge littered with pakoras and Reese’s Pieces that cannot be crossed except with soulful looks and tangential arguments. Most often we’re looking at a displaced South Asian character in the UK, North America, or Western Europe, searching for place, belonging, and an outer and inner shape to her identity. This protagonist has perhaps been displaced before birth, by her parents.

As South Asian literature (a term just as non-specific but functionally useful as Indian food) grew throughout the 70s and 80s to become an increasingly mainstream cultural force in the West, a generic calcification began to appear around certain elements. This thread of diasporic literature became a sub-genre unto itself, and it’s now a sure thing that you’ll find a disconnected-family/roots-rediscovery page-turner with exotic red silks, black braided hair, and perhaps a mango on the cover among the stacked books at Costco, or on a chainbookstore table under an “Eastern Journeys” placard. These books bear titles like The Golden Son (by Shilpi Somaya Gowda), The Orphan Keeper (by Camron Wright, who is white, but the book is “based on a true story” of kidnapping and orphan-selling in India, and therefore fits comfortably into this authenticity-rich sub-genre), The Hindi-Bindi Club (Monica Pradhan), and The Mistress of Spices (Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni). There is strong, sincere prose in many of these books, while others are solid entertainments. Regardless of literary quality, they typically hit enough nostalgia, authenticity, and exoticism points to score decently on Goodreads.

When these books are really bad, nuance is out the door, as mothers and fathers screech rules and edgy white girlfriends and boyfriends offer drugs. Some of this reflects the lived experience of many South Asians, of course, but the poles of the pure-if-backward East in opposition to the corrupt-but-free West in these stories is drawn so strictly that the books become fairy tales by default. Books that escape the codifications of the genre often interrogate it—Hanif Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia (later made into a television show scored by David Bowie and starring a pre-Lost Naveen Andrews) called bullshit on East and West equally. The protagonist is a 60s hippie teen whose father sets himself up as a junior maharishi in London’s suburbs, with unholy goals of sexual and financial enrichment. It’s possible for vendors of South Asian spiritual groundedness to make the move west, whether by plane ticket or by book—and it’s also possible for South Asian emigrants to the West, and for their children, to long for the truths of the past and a pure homeland.

“Regardless of literary quality, they typically hit enough nostalgia, authenticity, and exoticism points to score decently on Goodreads.”

Even white writers have been known to crave the authenticity of the imagined ancestral past that is the birthright of every second- or third-generation member of the South Asian diaspora. Getting back to the real, right thing is, after all, a key part of Elizabeth Gilbert’s overwhelmingly successful spiritual self-help/travel memoir, 2006’s Eat, Pray, Love, a cousin to a certain sub-genre of books in the widening field of South Asian literature. Gilbert’s travel experience in the book reflects a particularly modern privilege: allocating circumscribed experiences to particular cultures and geographies, designating each place with a desire or goal. In Gilbert’s predetermination of how her year of self-discovery was going to unfold, India was the pray-place, after her feasting in Italy. The pounds she gained in experience of gelato, cheese, pasta, and bread on what her friend Susan calls the “No Carb Left Behind” tour are to be abandoned, along with the spiritual clutter of her past, in her guru’s ashram. One of her ashram pals, “Richard from Texas,” describes the place where Gilbert starts her Indian sojourn as “a beautiful place of worship, surrounded by grace. Take this time, every minute of it. Let things work themselves out here in India.”

At that line, the quietude of Gilbert’s time in India, and its consequent artificiality, becomes striking: in exposing herself to spiritual truth, the overmastering fact of India’s population, its crammed density—”the crowd,” as Salman Rushdie put it in a 1987 essay, “The Riddle of Midnight,” on the separation of India and Pakistan—is nowhere to be seen. She’s in perpetual peace, with other seekers. From most accounts I’ve read, extending from the Raj to the present day, peace and quiet in India is an expensive commodity. In the country that Gilbert has allocated the role of finding her inner truth, she’s strictly averse to any outer experience. Her resistance to getting out of her Indo-spiritual mode by engaging with the country emerges as a reluctance to taste it:

A few times a week, Richard and I wander into town and share one small bottle of Thumbs-Up—a radical experience after the purity of vegetarian ashram food—always being careful not to actually touch the bottle with our lips. Richard’s rule about traveling in India is a sound one: “Don’t touch anything but yourself.”

This may not be explicitly racist, but it is hilariously cautious—100 pages ago, Gilbert was dining on the intestines of a newborn lamb, but in India she’ll decide that her needs are best served by staying in the ashram for the full term of her spiritual education. Like Amit Chaudhuri, with his aversion to the street food of Calcutta because it wouldn’t dovetail with his idea of a necessary experience of the city, Gilbert has a clear idea of what she’s there for. She didn’t come to India to eat. Where Italy was a place for gustatory hedonism, India is a place of spiritual honesty and reconstruction, and damned if she’s going to allow it to be anything else. Her time in the country, after her days of self-confrontation and looking for the yogic God in herself, ends with a flight out of “India at four in the morning, which is typical of how India works.” Maybe it is typical—I haven’t been, myself. And it’s likely that Gilbert has been back and experienced a fuller version of the country since. But can she make the call of what’s typical of the country or not after having spent a few weeks meditating in a series of quiet rooms?

Jhumpa Lahiri’s experience of Italy, a country she moved to in order to deepen a long-standing relationship with its language, speaks to another aspect of the inescapable realities of travel. In Other Words (2015), Lahiri’s written-in-Italian account of a mature writer coming to grips with a different language, can’t help but become a travelogue, as her Italian can only make the final leap toward fluency by her moving from America to Rome—a trip back to someone else’s old country, in pursuit of a language she wanted to make her own. Despite her advanced level of proficiency in the language, Lahiri’s white husband was taken by Italians to be the real native speaker in the family: “But your husband must be Italian. He speaks perfectly, without any accent,” a saleswoman tells Lahiri, ignoring her husband’s clearly Spanish accent and Lahiri’s higher level of fluency. The saleswoman can’t hear Lahiri’s better grasp of the language, simply because she doesn’t look like her Italian should be better than her white husband’s.

While Elizabeth Gilbert’s Americanness is often called to her attention in Italy, in relation to her body, her manner, and her clunky use of language, the sense of rejection is never as profound as the one Lahiri takes from her experience of her language being deemed inferior to her husband’s. Gilbert wanted to visit Italy to eat, to nourish herself in this place-away. Lahiri wants to absorb the country, to inhabit its language and ultimately the place itself. She’s confronted with the fact that her race disallows this from occurring once she leaves the domain of pure language and enters the life of the country: on the Italian pages she writes and reads, she can belong, she can have an authentic experience and be accepted by the language as her mastery of it increases. But in the streets, she’s still a brown woman among white Italians. Gilbert’s whiteness allows her to shape Italy to fit the preconceived experience she needs to extract; Lahiri can’t. To get the Indian experience she needs, Gilbert also has to shut out the country outside and stay in her ashram the whole time—even privilege and whiteness aren’t enough to corral the actual life of India on the other side of the meditation gates.

Nothing beats actual travel for a real education, they say (“they” quite often being bartenders or servers or students who spend off-seasons fucking hot Australians or Swedes in hostels and reporting back on markets and forest temples seen along the way). But entering the subjectivity of a novel or a travel memoir is a crucial supplement to a worldly education. Elizabeth Gilbert’s India is one I’ll never see, because I can as little imagine myself spending weeks in an ashram as I can envision going to astronaut camp or being good at sports. As a minor character says in the film Total Recall: “What is it that is exactly the same about every single vacation you have ever taken? . . . You! You’re the same. No matter where you go, there you are.” There’s a subtle difference between travel and tourism—one deeply bound up with authenticity. Elizabeth Gilbert largely accepts her role as a tourist, as she’s shaping each place she visits to the brand of experience she wants to emerge with. Jhumpa Lahiri’s sojourn in Rome (where she still lives, writing in Italian) is a purposeful inhabitation of another culture, a visit that’s meant to turn into a stay, and maybe one day into a kind of homecoming. Belonging and authenticity aren’t quite the same thing, and Lahiri, on account of race, cannot ever completely belong to this other place.

Great travel writing allows you to travel as someone else. And certain brands of writing about food or culture allow you to remember yourself as someone else. Part of the appeal of authentic-Indian cookbooks like Monsoon Diary and diasporic narratives like Sabrina Dhawan’s script for the Mira Nair film Monsoon Wedding, in which members of a dispersed Punjabi family return to Delhi for a wedding and end up confronting past traumas, is the chance to enter someone else’s remembering. We want to trace a journey backward, to its completion in the past. The more often a tale of returning to the real in past and homeland is told, however, the greater the chance is that its recurring elements start to ring false. It doesn’t help when the publisher’s marketing moves, such as inserting Monsoon into the title of a memoir-cookbook released a couple of years after Nair’s hit movie, transparently commercialize South Asian recollections and nostalgia.

This idea of traveling as someone else drew me to another Italian journey, a fictional one by a contemporary of Rushdie’s. In his novel The Comfort of Strangers, Ian McEwan talks about the moment of entering the authentic, as his husband-and-wife protagonists enter a space they realize they’d been dreaming of throughout their trip to Venice. Robert, the man who befriends the couple and eventually lures them into an experience so unpleasantly real it involves passing through sex into death, tempts them with the promise of a “very good place” for food. The place where they end up offers only booze, but even if their stomachs stay empty it nonetheless gives them something they truly crave. It’s the real deal, a place where people like them—outsiders—aren’t supposed to be.

Then, despite the absence of food, and helped on by the wine, they began to experience the pleasure, unique to tourists, of making a discovery, finding something real. They relaxed, they settled into the noise and smoke; they in turn asked the serious, intent questions of tourists gratified to be talking at last to an authentic citizen.

This is precisely the same experience-request that books by brown people are often asked to fulfill, and not only for the audience—often, the author also seems to want that experience of becoming an authentic citizen. A trip to the subcontinent is supposed to be more than a holiday, and a book about people of South Asian descent is supposed to be more than a novel. An audience may demand that it fulfill the function of literary tourism, offering not just a glimpse of another place and time, but an experience of authenticity. And for the diasporic writer? He or she gains the experience of that pleasure, unique to tourists, of making a discovery, finding something real. The disconnected experience of being a person in the West, let alone a person of color in the West, doesn’t lend itself to a sense of comfort or peace: fitting your own story to a narrative where answers are to be found in a familial, national past can be extremely soothing.

Is there a problem with these expectations existing in the genre? Only that they constrain and limit the potential methods of expression for brown writers. No page can be entirely blank when you have a general idea of the shape of what you’re supposed to write. For a diasporic writer, the hidden demand to play both tour guide and tourist could lead to a fulfilling negotiation of identity, family, and place—and it could also seal off other paths of exploration, other stories the writer may feel more driven to tell, to an audience that he or she may suspect doesn’t exist. A tacit request from readers to create an authentic experience can, ironically, result in the opposite: false stories, or stories with false elements burying truthful details and experience, built on conventions created by other writers and the categorizations of the publishing industry.

__________________________________

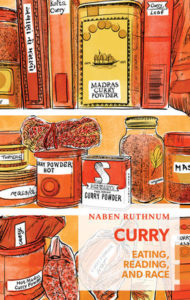

From Curry: Eating, Reading and Race. Used with permission of Coach House Books. Copyright © 2017 by Naben Ruthnum.