Crossing the Atlantic During Britain’s Darkest Hour in World War II

Doug Most on the Voyage of the RMS Scythia and the Beginning of America’s Preparation For War

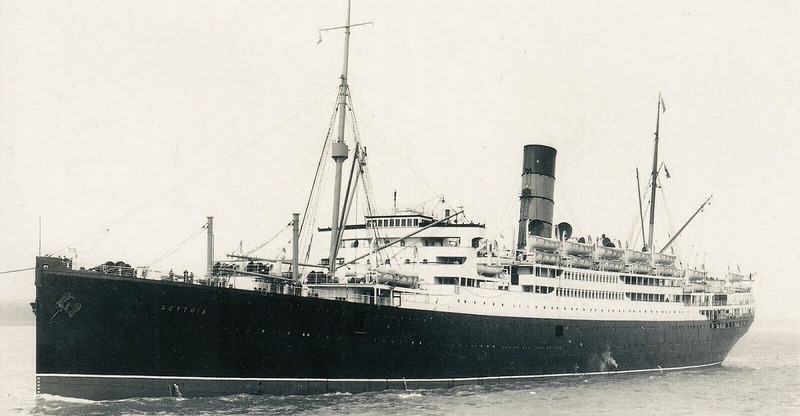

Housewives and civil servants, students and engineers, merchants, authors, and government officials, they came from the city and the countryside, from every corner of Great Britain. They arrived on a gray autumn Saturday, September 21, 1940, with all the anxiousness expected before a long journey. A stream of passengers, 806 of them to be precise, lined up at the Customs Shed at the Port of Liverpool, tickets and paperwork in hand, to board the Cunard White Star luxury ocean liner RMS Scythia.

She was loaded up with everything from engine grease to asparagus, dishrags to lightbulbs, noodles to pillowcases. An army of polishers, painters, cleaners, plumbers, upholsterers, and even a piano tuner finished preparing her for the trip, and the crew got ready as well. Chefs who had to provide their own kitchen knives sharpened each one for meal prep, and the women officers made sure their evening dresses were ironed and hanging.

Transatlantic crossings were routine journeys for steamships like the Scythia, a 600-foot, black-hulled vessel that featured an elegant dining hall and a movie theater, and could cross from England to New York City in less than two weeks. In the days after her maiden voyage in 1921, she was described as “the ship of the future” with her size, speed, and the capacity to carry more than 2,300 passengers.

For the passengers boarding the Scythia, the question seemed to be, where would they be safest: At home in England….Or out on the ocean?

As the passengers continued boarding—third-class passengers first and first-class last—the ship’s crew checked each person’s papers to confirm their age, occupation, native language, permanent residence, and marks of identification like scars or birthmarks. If their ship was attacked, that’s how bodies could later be identified.

Blending in among the passengers were two sharply dressed men, one of them taller, stockier, and older, the other more athletic-looking and toting a brown briefcase. They were not wearing uniforms or badges, any hint that they were traveling on behalf of the British Admiralty. The older one seemed more serious, business-minded, while his companion tended to smile and laugh more easily. The briefcase was the only hint that they were traveling on a work matter rather than for pleasure.

As the ship continued to fill, something different about the passenger manifest became apparent. There were so many children boarding. From toddlers to teenagers, there were 260 of them on the list, almost one-third of the total number of passengers. The majority of them were traveling as a group of refugees organized by United States First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

Just before boarding, many of the children had been filled up with ice cream to help distract them from what lay ahead. It seemed to work. They ran up the ramp onto the deck of the ship and flashed a thumbs-up sign to people back onshore before scrambling off to play. Keeping their spirits up on the journey would fall to their escorts or parents, and to a ship orchestra that was prepared to lead them in song. It would not be easy. Cunard’s ships displayed evidence all over of the danger that lay ahead.

Posters alerted passengers on what they should do in the event of an attack. One urged them to keep flashlights and life preservers on their body at all times, to sleep in their clothes for the first two days after leaving England, and to be sure to attend dinner on time so that the watertight doors separating the dining room and kitchen could be kept closed. A second poster was more grave. “If an enemy attack is anticipated, the following signals will be used: Four blasts on the ship’s whistle and four rings on the electric gongs. At this signal, passengers must take cover below C Deck in the nearest dining room and remain under cover until the attack is over or the signal is made for the boat stations.” For the unaware, that terror-filled signal would be six short blasts followed by one long one.

Only a few days earlier, German submarines had torpedoed the SS City of Benares as it carried British families to Canada, killing seventy-seven children. Now, for the passengers boarding the Scythia, the question seemed to be, where would they be safest: At home in England, where a German invasion seemed imminent, where bombs were raining down and the London Underground was being used as an air raid shelter? Or out on the ocean, sailing on a ship crossing the Atlantic, where German U-boats lay in wait, torpedoes at the ready?

*

A year had passed since Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Britain declared war on Germany two days later, launching a second world war a little more than twenty years after the first one ended. Using precision aircraft assaults and relentless submarine attacks, Germany swiftly seized control of the European coast, from the northernmost region of Finland south through Sweden and Denmark, down past Paris, and all the way to the Pyrenées Mountains, a stretch covering 2,500 miles. German chancellor Adolf Hitler had France, Denmark, and Sweden all in his hands. But he recognized he would never control Europe until he had seized its largest country, and he had fixed Great Britain in his crosshairs.

In a recent speech to the House of Commons, Prime Minister Winston Churchill had used words like “slaughter,” “ruins,” and “casualties” in describing the state of the war. He asked his fellow countrymen and women to remember those fighting to protect them. “Never was so much owed by so many to so few,” he said.

For a leader just three months into his term, Churchill exuded confidence in his address. He said forcefully that Britain would defeat Germany. “Our geographical position, the command of the sea, and the friendship of the United States enable us to draw resources from the whole world and to manufacture weapons of war of every kind,” he stated. In the days following his speech, Britain’s situation grew more bleak.

On Sunday, August 31, two Royal Navy destroyers were sunk off the Dutch coast, German planes continued their assault on British airfields, and Nazi fighters dropped bombs across England, marking the beginning of the London Blitz. The toll just for the Royal Air Force over the month was staggering—344 aircraft downed and 139 pilots and crew members killed—and it was about to get worse. German U-boats sank 47 British merchant ships in 1939, vessels that carried precious food, raw materials, weapons, and supplies to troops. Britain was on its way to losing another 395 cargo ships in 1940, not including the hundreds more that sustained so much damage they were out of service for months.

As Germany’s attacks across Europe intensified, the U.S. president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, faced the most challenging crisis of his eight years in office. Roosevelt was a distant cousin of Theodore Roosevelt, the nation’s twenty-sixth president, whose two terms in the first decade of the 1900s were marked by prosperity and excitement of the new century. The America that Franklin Roosevelt inherited in 1932 looked nothing like that. President Herbert Hoover’s words at his 1929 inauguration, “In no nation are the fruits of accomplishment more secure,” proved tragically inaccurate.

Ten months later, Americans saw their savings vanish almost overnight and the arrival of the Great Depression. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, after peaking at 381 points in September 1929, plunged to 41.22 in the summer of 1932, its lowest mark of the century. It would not surpass its pre-crash high until 1954, an entire generation of anguish. By 1940, FDR, now fifty-eight, had steered the economy mostly straight after eight years of New Deal programs. But now he faced an entirely different kind of crisis that challenged his unrivaled intellect and blue-blooded background—from boarding school in Groton, Massachusetts, to Harvard College to Columbia Law School. He spoke German and French. He was the son of wealthy, sixth-generation Americans, a former governor of New York, assistant secretary of the Navy during World War I, and a survivor of polio.

If Hitler was going to build more submarines, Roosevelt believed America needed to race to build more ships.

And he’d come to despise all that fighting stood for.

“I have seen war on land and sea,” he once said of his experiences. “I have seen blood running from the wounded. I have seen men coughing out their gassed lungs. I have seen the dead in the mud. I have seen cities destroyed…I hate war.” Now war seemed inevitable. America’s closest ally was teetering on the precipice of collapse to a maniacal leader, which would give the Nazis control of Europe. But Roosevelt’s hands were tied. He could not fire first, even if he wanted to. The Neutrality Act of 1939 forbade American ships from entering a combat area and firing on any vessels if it was not at war with their country.

But it did not forbid Roosevelt from readying America for war with a new maritime strategy. He told Admiral Emory Scott Land, the director of the United States Maritime Commission, to begin drawing up a plan for an unprecedented expansion of the nation’s moribund shipbuilding industry. Roosevelt’s motivation came from the intelligence he was hearing about what was happening across the Atlantic, where Germany was ramping up its own production of hundreds of U-boats. If Hitler was going to build more submarines, Roosevelt believed America needed to race to build more ships. The two countries were not yet at war with each other. But that day was coming.

*

While the Neutrality Act restricted Roosevelt’s military might, forcing him to wait and watch as the war in Europe escalated, his wife faced no such moral dilemma. Nor did she have the patience to sit idly by as innocent families were torn apart. In the war’s earliest days, Eleanor Roosevelt personally tried to sponsor a single refugee out of Europe. As the situation worsened, she broadened her efforts. The first lady saw the threat Nazis posed to British families, and so over the summer of 1940, she, along with a group of child refugee advocates, formed the United States Committee for the Care of European Children, with the mission of admitting orphaned and unaccompanied children.

In its first few months the group successfully relocated hundreds of children, both Jewish and non-Jewish, and it would eventually rescue more than 1,300. One passenger boarding the Scythia seemed unworried by the direction of the war in Europe. The British citizen, journalist, and author H. G. Wells, whose science fiction novels The Time Machine and War of the Worlds had made him something of a national treasure, was traveling abroad on his seventy-fourth birthday. As he prepared to embark on a ten-week lecture tour in the United States and Canada, Wells expressed confidence that Germany’s momentum would stall and Britain would prevail. He told reporters America should stay out of the war. “Your party politics would swamp anything like a reasonable settlement,” he told the newspapers.

If Wells had only possessed the same knowledge of how the war was going as those two sharp dressed businessmen on board the Scythia, he might not have been so brash in his thinking.

A young British shipbuilder named Robert Cyril Thompson—Cyril or RC, he was called—carried the briefcase. Inside were architectural drawings for a new type of cargo ship his company had built, bigger than any cargo ship Britain had ever seen, and with a strangely shaped hull that looked nothing like an ordinary merchant vessel. He was accompanied by an older, experienced marine engineer named Harry Hunter. The blueprints with them had been seen by only a handful of senior officials inside the British Admiralty who believed this ship represented precisely the type that Britain needed.

With all 806 passengers on board and her dock ramp safely pulled away, the Scythia set sail, easing into the Atlantic under the light of the moon, a silhouette in the middle of an air raid. Searchlights beamed into the orange and black nighttime sky while two crew members stood on deck, watching as British antiaircraft guns fired away at German fighters buzzing past like a swarm of bees. Ahead, 3,140 miles of treacherous waters awaited.

__________________________________

From Launching Liberty: The Epic Race to Build the Ships That Took America to War by Doug Most. Copyright © 2025 by Doug Most. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

Doug Most

Doug Most, a native of Rhode Island, is a lifelong journalist and author whose career has spanned newspapers, magazines, and universities up and down the East Coast, with stops in Washington, DC; South Carolina; New Jersey; and Boston. He was named Journalist of the Year while at The Record in Bergen County, New Jersey, for his coverage of a tragic story about two teens charged with killing their newborn, a story he turned into a true-crime book titled Always in Our Hearts. After a stint at Boston Magazine, he worked for fifteen years at The Boston Globe, as the Sunday Magazine editor, and deputy managing editor/special projects. His articles have appeared in Best American Sports Writing and Best American Crime Writing. His 2014 nonfiction book, The Race Underground, told the story about the birth of subways in America, in the late 1800s and was adapted into a PBS/American Experience documentary. The New York Times called the book “a sweeping narrative of late-19th-century intrigue.” He works now as the executive editor and an assistant vice president at Boston University. He holds a BA from George Washington University in political communication.