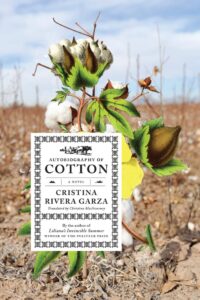

Cristina Rivera Garza on Writing a Genre-Blending Excavation of Family History

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of Autobiography of Cotton

I have long admired the work of Cristina Rivera Garza, the much lauded writer of novels, short stories, poetry, essays and criticism, translator, University of Houston Distinguished Professor, founder and director of the first Ph.D. program in Creative Writing in Spanish in the US. I featured her dazzling speculative noir novel The Iliac Crest as a best book of 2018 in my BBC Culture column. In 2019, she won a MacArthur “genius” grant for “innovative, transnational fiction that investigates memory, gender, and language,” and published Grieving: Dispatches from a Wounded Country, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle award in criticism. She won the Pulitzer Prize for her heartbreaking and powerful memoir, Liliana’s Invincible Summer: A Sister’s Search for Justice (2023). This, after countless international awards, including the Roger Caillois Award for Latin American Literature, the Anna Seghers Prize, and winning the International Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize twice.

We first met in 2017 when I was moderating a panel celebrating the centennial of Juan Rulfo at the Bay Area Book Festival. She was well versed in the work of the Mexican author known as the father of magical realism (he ushered in the Latin American “boom” of the 1960s and 1970s), having recently published a critical book on his work, Había mucha neblina o humo o no sé qué. She described reading Rulfo’s classic novel Pedro Paramo in high school—an assigned book which seemed more appealing once it was banned, and richer in influence upon rereading multiple times. “Rulfo gives voice to the rural people, those who have had no voice,” she noted.

Her own fiction often centers characters on the margins. Her novel No One Will See Me Cry (1999, English translation by Andrew Hurley 2003) features a photographer at an insane asylum in 1920s Mexico, and his obsession with a patient, a former prostitute he believes he knew when they were younger. In his El Pais review, Carlos Fuentes called it “one of the most notable works of fiction not only in Mexican literature but in the literature of the Spanish-speaking world at the start of the twentieth-first century…Rivera Garza imagines, like no one else has done in Mexico since José Revueltas, the tragic options and the psychic turmoil caused by revolutionary theory and action.”

In Autobiography of Cotton, first published in 2020 and launching this month in an English translation by Christina MacSweeney, Rivera Garza follows Revueltas’ trail through the past and present of a Mexico-US border town. His novel Human Mourning is central to the weave. “The agrarian experiment has already failed when the novel opens,” she writes of Human Mourning. “A small group of impoverished peasants witnesses the death of a child, and death—the presence of death, the bitterness of death, the sweetness of death—impregnates their surroundings. Repeated flashbacks let the reader see and feel the cotton fields, especially the labor that transformed tracts of dry land into meadows of white gold.” At one point, she imagines Revueltas locking eyes with her grandfather, José María Rivera Doñez, one of the thousands of striking cotton workers he has come to support.

In the finely connected layers of Autobiography of Cotton she also includes archival papers, history, contemporary road trips in the borderlands, nuanced references to dozens of intellectual treatises, revelatory details about the shifting of the land, and a personal narrative embedded with the myriad discoveries she makes about her own family. “We come here to live together with our dead,” she writes. And later, “Sometimes a book is a form of return: a refamiliarization and a reparation. This conversation that starts up again after years of silence.”

What inspired Autobiography of Cotton? I asked Rivera Garza in our email conversation. “When discussions about immigration and the US-Mexico border became increasingly vicious, I almost instinctively turned to my own history as heir to entire generations of working-class migrants in the United States,” she noted. “I knew—and had lived through—a radically different experience of the border but realized, and quite painfully so, that I did not know enough. I had overheard plenty of stories at home but knew little for certain. What began as a curiosity at first, and then became a raw desire to honor the lives of the people that had made space for me in this country, catapulted me into years of research and writing. We turn to the past when the present is unbearable. We turn to the past, dashing through the dark, carrying questions that flare like messages set on fire.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: You frame Autobiography of Cotton with José Revueltas’s novel Human Mourning, which resurrects a story lost to time. You open with a scene from March 16, 1934, as 19-year-old Revueltas arrives on horseback at Estación Camarón. He has come from Mexico City to support the imminent strike by thousands of agricultural workers. The surroundings, the wild northern wind, the design of the cottonfields in the desert of the northern territory of Mexico, the silence of the striking workers, inspire his novel, which includes the 1937 exodus from Estación Camarón after a devastating flood and drought. In your conclusion you make note of “the banishment of Estación Camarón, and particularly the strike of 1934, from the collective memory,” a punishment of sorts, as it becomes a ghost town, never spoken of, kept alive only by Revueltas’s novel. When did you first read Human Mourning? How would you describe José Revueltas’s influence on your work?

Cristina Rivera Garza: José Revueltas is the great radical writer of the 20th century. He not only was a self-taught communist activist who went to jail at least twice in his lifetime, but also, and perhaps because of this, a writer of uncompromising freedom and incredible range. I have described him (in a long essay included in Geological Writings, a book not yet translated into English) as an avant-garde political neo-materialist and unapologetic experimentalist. His prose—muscular, incantatory, of religious overtones—has no parallel in Mexican literature, contemporary or otherwise. Human Mourning, the novel he published in 1943, was read, and tediously criticized, by his contemporaries (such as Octavio Paz) as a faulty work of fiction.

Fiction is the amalgam that allows disparate elements to forge a whole. It is less a blend and more a sustained collision.

When, thanks to a conversation with my colleague and friend Max Parra, I went back to this book, I realized that Human Mourning was way more or other than fiction. In it, Revueltas boldly marshals forms of writing we associate with anthropology or social sciences or the grammar of political manifestoes. His emphasis on the materiality of emotion, the agency of rocks and other living and non-living entities, as well as his understanding of deep time as a “thick time” or tiempo denso, mark him as a thinker of our times. His meanderings through Estación Camarón not only gifted me precious pieces of information about a place in which he coincided with my grandparents but, most importantly, offered me a larger convulsive approach to both materials and writing. Long live Revueltas!

Let´s not forget Gloria Anzauldúa, another guiding light in this book. This legendary Chicana feminist writer and healer led me through the US side of the US-Mexico border with her wit and rage and infinite wisdom. Her writing, which is also convulsive, taught me how to move freely and fearlessly through the seven or so layers of the Spanish English trenza I speak now, and with which I write. Her experience with cotton and with cotton fields in southern Texas accompanies the evolution of the character of my paternal grandmother, Petra Peña, a double rock embedded in her very name.

JC: Autobiography of Cotton also seems in conversation with Juan Rulfo, not simply his ground-breaking 1955 novel Pedro Páramo, but his work life and travels throughout Mexico, including his decades with the National Institute for Indigenous People. Was he a companion on this journey through intimate personal and powerful global history?

CRG: I’d written a book about my reading of legendary Mexican writer Juan Rulfo way before I embarked on Autobiography of Cotton. For Había mucha neblina o humo o no sé qué (a work yet to be translated into English) I consulted materials others had overlooked and focused on Rulfo’s polemical years as employee of the Comisión de Papaloapan, the state agency responsible for the massive hard-infrastructure project of the Miguel Aleman Dam in Southern Mexico.

At the center of the controversy laid the forced displacement of indigenous communities brought about by this project. Rather than side-stepping the issue, I confronted directly and with archival documents in hand—which, incidentally, did not gain me the favor of the powerful Juan Rulfo Foundation. Había mucha Neblina o humo o no sé qué is not only the predecessor of Autobiography of Cotton, but also the start of what I conceive as a materialist family trilogy that starts with Autobiography, follows with Liliana´s Invincible Summer, and closes with a book I’m currently writing.

JC: You describe archival work tracking down your own family’s past. What sources were most valuable?

CRG: My research was manifold and extensive. I consulted local and federal archives both from Tamaulipas, the state in northern Mexico where I grew up, and Mexico City. Documents ranged from official descriptions of the cotton experiment led by engineer Eduardo Chávez on the Mexican side of the US-Mexico border to inventories listing of the belongings carried by deportees returning to Mexico. I famously confirmed José Revueltas’ participation in the 1934 strike in Estación Camarón by combing through telegrams exchanged among local and state police authorities. What a moment of bliss this was! I travel through the affected areas, conducting what others would call field research. I interviewed and filmed old members of the community. And I, of course, made use of family materials—which I would now describe as items of an affective archive—such as photographs taken by my father or mere gossip. Never underestimate the value of gossip both as an informational tool and as an epistemology!

JC: You mention that the violence in northern Mexico today made your research travels risky at times. (It’s not safe to drive after dark, and at one point you realize you’re within miles of Allende, the site of the 2011 massacre of civilians by a group from the Los Zetas cartel.) Was the question of your personal safety the most difficult part of your research?

CRG: Once brimming with opportunity, the places I explore and go through in Autobiography of Cotton lie now devastated by the so-called War on Drugs. I’d like to tell you that I faced no real danger while wondering through the Mexican and US borderlands, but that would be a lie. On the other hand, I was no hero—many people confront extreme violence and terror in their daily lives with far greater dignity and grace. One of the most emotionally striking parts of this research includes my realization that only one generation separates me from my indigenous past—a fact that was not common knowledge in my family until now.

It was also difficult, to say the least, to uncover that my paternal grandfather had “eloped” with his third and much younger wife, my father’s mother. The difficulties in translating the legal language of the time—was it eloping or kidnapping?—only gestures toward the turmoil I went through upon reading the marriage certificate. Placed in the context of rural Mexico, this was a common way for poor people to evade both the cost of a civil marriage and, at times, the authority of the family. But this document, which compelled me to interrogate my past more fully, unlocked the doors for a discussion on gender violence in my family history, most urgently the history of my sister’s femicide.

JC: How did you develop your agricultural details—the irrigation, planting, harvesting of cotton, then, after the boll weevil destroys that option, sorghum, and ultimately, in the 21st century, fracking arrives.

CRG: Local and national archives are awash with documents dense with agricultural details. Since I wanted to preserve and listen to the language of cotton in this book, I had no alternative but to rely on the many documents where this voice, the voice of cotton, had left a distinctive mark. While “untranslated,” documents on agricultural techniques, fertilizers, bank maneuverings, and the like offered me an entry—narrow and tilted, perhaps, but an entry nonetheless—into this language.

JC: How do you think of its blend of fiction and memoir? Documentary fiction?

CRG: Genres are not well-defined or stable territories but porous living entities that mutate and challenge us at will. If we think of genre as a host—and I do—you can see how fiction as that which hosts, that is, welcomes and embraces, other genres to better serve the materials I’ve congregated. Fiction is the amalgam that allows disparate elements to forge a whole. It is less a blend and more a sustained collision. It less a display of (cultural) might and more an exercise of (formal) shapeshifting. Fiction does not compensate for a lack of information but makes room for—and adapts itself to—the formal possibilities and modes of engagement opened by other genres. Ultimately, what matters are the materials. Formal decisions are rarely made by authors alone; they emerge through close engagement with—and often in contention against—the materials themselves.

JC: I was fascinated by your connections to Houston. How were you able to discover and interweave the historic threads in this part of the book?

CRG: Life and writing interweave in mysterious ways. I was offered a job at the University of Houston—running a Ph.D. program in creative writing in Spanish, the first of its kind in the country—just as I was conducting research for this book. I had already traveled through the region and done much of the archival work when I accepted the offer, but I had yet to encounter face to face with a city that was central for my family history: Houston. True, I had lived in Houston during my PhD years, but back then I was not thinking or problematizing my family migration or my own. Returning to Houston allowed be to conduct interviews, for example. But it did something even more consequential: I placed my feet on the footprints left by my ancestors. I brought my body to the site of belligerence and bliss. Memory is seldom an intellectual feat.

JC: How did you select the series of narrative insets that reinforce the themes in Autobiography of Cotton—James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the work of Lebanese theoretician Jalal Toufic, American historian Sven Beckert, and others.

Change me, drastically if possible. Transform me. Make me other. That’s what I ask of books—both when I read them and when I write them.

CRG: Books are not forged in isolation. I’m interested in a disappropriative aesthetics (an approach I explored in The Restless Dead, published in English not too long ago) that discloses and openly engages with the materials I employ as a writer. I move here in countercurrent with traditional fiction, which all too often denies this productive relationship with others, through stratagems such as the “author’s genius.” I’ve said elsewhere that research is a form of caring, and caring the only disposition that allows writers to come close to the materials they’ve chosen, especially if these materials relate to poor or disempowered peoples frequently overlooked by official narratives. It is not identity, I’d argue, what “gives me permission” to delve into my family history, but the care I have devoted to their histories and their bodies. Others have navigated similar ethical quandaries, and I wish to honor that work. My book belongs to ongoing discussions that live in and outlive literary dilemmas.

JC: One section of this book is called [Coming from a place that isn’t on the map]. Your narrative throughout grapples with the question of nomadic life, erasure of history and family history, the questions you are answering (including the fact your grandparents who worked the fields at Estación Camarón were indigenous). “We are still those nomadic farmers,” you write at one point. “We like leaving. We like producing the distance in which memories and writing later fit. Melancholy. Rage. We like to disobey. Whenever there is conflict or the situation becomes unbearable, we open the door and out we go.” Did your work on this book give you a stronger sense of the place you come from, the fluid structure of yourself?

CRG: Change me, drastically if possible. Transform me. Make me other. That’s what I ask of books—both when I read them and when I write them. I came to look at, understand, and envision my I, both as a first-person singular pronoun but also as a first-person plural pronoun, in unexpected ways when I wrote Autobiography of Cotton. My relationship with my ancestors and with my son has been altered forever because of it. My engagement with the United States, a country I feel in my bones because it lies in my bones, has sharpened. The sorrow and rage I feel as I bear witness of the unleashed war against migrants now comes from someone who knows she belongs. This is also my war—my resistance to it, my torment over it, my struggle against it. This is the beauty and dangerousness of literature, isn’t it—it can transform lives. Such potency.

JC: How has your 2024 Pulitzer Prize for your memoir Liliana’s Invincible Summer affected your life and work?

CRG: Awards have the virtue of shedding light on issues that matter profoundly to authors. I’m glad Liliana´s Invincible Summer has contributed to an often-neglected discussion in the English-speaking world: gender violence, more specifically femicide, what some experts have deemed as a silent epidemic. Three women in the United States are killed by their intimate partners every single day, and numbers grew exponentially during the pandemic. As I say in conjunction with my feminist friends in Mexico and elsewhere: Justice for Liliana, Justice for All. !Ni Una Más!

JC: What are you working on now/next?

CRG: I’m slowly writing the closing volume of my materialist family trilogy—but I will get to it when I write the last sentence.

__________________________________

Autobiography of Cotton by Cristina Rivera Garza is available from Graywolf Press.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.