Creating the Cafe Society I Always Dreamed Of

On Starting a Literary Salon in New York City

Somewhat improbably, I moved to New York in 2004 to start a literary salon and writers’ space in a grand, but run-down mansion on Gramercy park, the home of a larger 19th-century arts and social club. They leased a space to me and my best friend for practically nothing, a derelict former artists’ studio that we renovated ourselves from top to bottom. We carted away 50 years’ worth of junk, redid damaged floors, hung ornate, absurd toile wallpaper and, admiring the impressive, if slightly ersatz, elegant space that we were now in possession of, decided it would be a reasonable business venture to start a members’ club for authors and literary-minded people. I had grown up in the thrall of 19th-century French novels with their tales of salons and the glittering urban life of artists and writers and glamorous women and this was my way of bringing into being the life I had always thought I wanted.

The worst of this illusion I blame on reading Proust in college. I had wanted to be a writer for as long as I could remember, but at 20 found myself, much like narrator of In Search of Lost Time, bursting with intensely felt moments and literary ambition, yet somehow not quite getting around to writing that masterpiece I had planned. My identification with the prickly, overwrought young man, as well as a general predilection for all things Second Empire (realist novels! courtesans! swan’s neck chairs!) made me take this book to heart—my personal template, a model for the writer’s life. I already had the sickly constitution, an embarrassing fascination with dukes and duchesses, a tendency to lapse into purple prose, and wild lurches between equally crushing arrogance and insecurity. At the time, young and foolish as I was, I thought that all I lacked on my journey to be a writer, was the world. That bright and sparkling life of the metropolis, where important things happened, fame, celebrity, brilliant writers and artists, the ferment of intellectual and social life. I wanted a salon. But we also wanted to pay our rent so my friend and I came up with the idea of charging membership fees. In return, we would offer places to write during the day and host readings and lectures at night—creating the café society that I had always dreamed of, more or less from scratch, with a lot of moxie and a few wine sponsors.

The idea sounds totally absurd now, and was pretty audacious even then. That my friend and I were both attractive, clever, 25-year-olds, blonde and brunette, appealing in that eternal Betty and Veronica, Gentlemen prefer Blondes dialectic, or that my friend was already well placed in a certain slice of the upper echelons of the kind of downtown scene where artists and heiresses had been mixing ever since Warhol, all certainly helped our endeavor. But the success of our salon once it opened was so surprising, so unlikely that only looking back now does it seem so clearly exemplary of its time and place—just one of the many bubbles rising in the strange effervescence of those years in New York. The city had risen on waves of capital from the dot com boom of the decade before and it still felt like there was money everywhere.

It wasn’t just that temp jobs were plentiful, or that the internet still seemed a place of wild opportunity and venture capitalists were circling over the bright young people looking for the next big thing to invest in, but something seemed to have happened in the years after 9/11, a kind of eagerness to reassert the communal, artistic life of the city that looking back seems painfully earnest. Articles were written wondering whether the end of irony had arrived. The heroin chic nihilistic 90s were passé. Bars were trading out their sleek white modular interiors for walls of books. Freemans was the hottest restaurant in town with its taxidermy and we, in our raggedy Victorian mansion, baking homemade scones for weekly poetry readings, all seemed to be part of this wave of longing for a tactile, authentic past.

Everyone wanted to participate. n+1 had recently started, Lapham’s Quarterly was new, the New York Observer still served as a kind of campus broadsheet. We all read Gawker for gossip about the people we saw at parties the night before and there was a palpable sense that the life I had always read about with longing was happening and happening right around us. Advertisers were just catching on to the idea of cultural capital. The notion of influencers, while it hadn’t yet reached the slick, monetized heights of Instagram on the horizon, was in the air and it seemed every corporation wanted to be associated with the cool, young things, and fought for the privilege of funding all our parties. Starting a magazine? Hosting a happening? Opening a gallery? Someone wanted to pay for it. Every night we floated from one cross promotion to another, Adidas paid for our beer at one book party, a new brand of rum provided free sushi at another, corporate largesse poured into Manhattan and we all rose on its tide, still at a delicate remove where it felt commendable, this hustling to make our artistic dreams a reality, a pre-lapsarian idyll before everyone had learned to turn the tricks of spon-con.

“Were we, bright, privileged, intellectually minded young people guilty of a lack of attention, a callous distraction in pursuit of an imaginary New York.”

But nostalgia is a tricky thing of course, and to take as a model the artistic and cultural flowering of the Belle Epoque and Gilded Age is to also tarnish yourself by association to a period of infamous economic inequality, a comparison that our subsequent decades have only proven accurate. We knew what was coming, in a way; the storms had been gathering over the city. Loathing the mayor was one of the things that bound us together and “Giuliani is ruining New York” was the refrain that echoed through the 90s. His broken windows policing and discriminatory housing policies caused irreparable harm to huge parts of New York, engendering enormous suffering. But despite his obsession with law and order, his racially motivated persecution, his music hall villainy, twirling a mustache and enforcing cabaret laws to literally stop New Yorkers from dancing, he hadn’t totally eradicated the sense of possibility that pulsed through the city. His over-the-top fascism (as we liked to call it) called forth pockets of resistance—the illegal art space, the punk venue, out of the way spaces where one could still scratch out remnants of an alternative, creative life. Bloomberg and his developers would wipe these last spaces of transgression from the map with a bureaucratic efficiency that has rendered the stories of New York of my youth sounding like fairy tales.

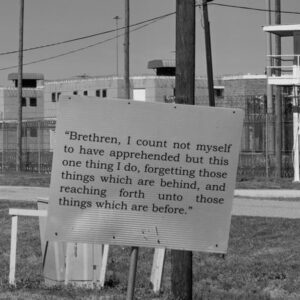

But then, Proust’s story also ends in a darker time. The final volume takes place with the WWI Gothas dropping their bombs over Paris, the war being the calamity that gave lie to all that remarkable confidence of the Belle Epoque. And it’s hard not to draw similar conclusions about my own golden youth. Not that the election of Trump is quite comparable to the carnage of the First World War, but with climate disaster imminent, and the horsemen that accompany it—inequality, war, famine, displacement on the move, I can’t help but feel a kind of retroactive shadow, the sense that we were all dancing while the darkness loomed. Were we, bright, privileged, intellectually minded young people guilty of a lack of attention, a callous distraction in pursuit of an imaginary New York that now casts all my champagne-drenched memories of parties and readings and launches in the chill light of a new reality?

As Proust’s narrator looks around at the final party of the book, he realizes with some surprise that he and everyone he admired in this social blaze have aged. The glittering society figures he idolized have been revealed as corrupt, infirm, debauched, inconsequential while a new crowd has risen in their places. The circle of parties continues. The narrator, my erstwhile guide to this writer’s life, realizes that to write his book, he must leave the world and dedicate himself to the study of memory, well that’s a simplification—he invented a whole artistic and philosophic schema to describe that process, but even for the less brilliant, the simpler truth stands out. That the pursuit of deeper artistic endeavors does not take place with a disco ball over head and cocktail in hand.

And so, I sit typing in a quiet room on a quiet street in Brooklyn, a baby sleeping in the next room, retired to the private, the domestic, my hours consist of writing, thinking, remembering those long-ago parties, translating them into the pages of a novel. I know the world will keep turning and the parties will keep happening and it’s only the misapprehending egotism of age that leads us to think the carousel stopped as soon as we stepped off. The brilliant young people are dancing in Bushwick, though perhaps now at a fundraiser for the Democratic Socialists of America, and someone has started a literary salon in Long Island City, but now in the service of diversity and inclusion in the literary world and New York abides, to be written about by a new generation of melancholy observers before they too bow out and turn to their desk to try and make sense of it all.

Iris Martin Cohen

Iris Martin Cohen grew up in the French Quarter of New Orleans. She holds an MFA from Columbia University and studied Creative Nonfiction at the Graduate Center, CUNY. She currently lives in Brooklyn. The Little Clan is her first novel.