Elisabeth’s hands are resting on her stomach. She feels every vibration under her skin. The hands rest there with the same expectation as during her pregnancy—that movement is on its way, that the child will swim towards the hands, that it will turn there, twist, push, roll. Movements that get stronger every day. But later, when the child was supposed to be somewhere else, the hands stayed there and there was always a vibration, a shudder, movement. The child had never gone away. Elisabeth closes her eyes and feels the miniscule movements underneath her fingers. Then a bang. Something falls upstairs. She hears Coco swearing.

‘Stay away,’ Elisabeth whispers. Upstairs something large is pushed across the floor. Elisabeth sits up. Will come in a minute. Will want to talk. She hears a door and she is already sighing, that will be her. No footsteps follow.

I just want to lie down for a bit. Can’t a person just lie down? It’s quiet again now. What is she up to? Elisabeth throws off the covers, sits on the edge of the bed.

Will need coffee for sure. What a lot of coffee that child drinks. Everything runs out quicker with her in the house. Where has she got to?

Elisabeth struggles to her feet and grips the rollator. She rolls it across the room, lifts it over the doorstep, goes along the hall, listens from the bottom of the stairs.

‘Coco?’ No reply.

‘Coco?’ Again nothing. She must realise it’s tiring, that shouting.

‘Coco?!’ Does she want coffee or not? It’s much too cold in the hall.

‘Cooocooo?!’ Finally a door and footsteps.

‘Yes, what is it?’ Coco stands at the top of the stairs. ‘Do you want coffee or not?’

‘Coffee?’

‘Is it such a difficult question?’

‘Have you already put it on?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Are you putting coffee on?’

‘If you want coffee.’

‘Do you want to have coffee. . . ? Together?’

‘Do you want coffee?’

‘I’d be happy to have some coffee, but I’m studying. But if you already have some or you’re putting some on. . . ’

‘Well, then I’ll put some on, if you want coffee.’ Elisabeth sighs, turns her rollator, and goes to the kitchen.

‘What’s the matter now?’ Coco calls after her.

‘I’m just not used to it,’ Elisabeth calls back as she enters the kitchen, ‘having to make coffee for someone else all day again. I drink two cups in the morning, myself.’

“Later, when the child was supposed to be somewhere else, the hands stayed there and there was always a vibration, a shudder, movement. The child had never gone away. Elisabeth closes her eyes and feels the miniscule movements underneath her fingers. Then a bang. Something falls upstairs. She hears Coco swearing.”

Coco comes stomping downstairs, walks past her into the kitchen. ‘You’re the one who suggested coffee!’

Elisabeth fills the kettle. Puts the full kettle onto the rollator and wants to walk to the other end of the counter with it. The water sloshes out.

‘Can’t you just put the coffee on? It’ll be much quicker.’

‘If you want coffee, Mum, you can just ask for it, you know. I’m more than happy to make coffee for you.’

‘No thanks, I don’t drink coffee in the afternoon.’ Coco stares at her, the kettle in her hands. Dark look. Away with her, away. Don’t ask, don’t try to understand what it is this time. ‘What?’ she shouldn’t have asked. Leave it, leave it. Let it go.

‘I was studying.’

‘Yes, and I was having a lovely rest in my bed. I don’t mind being on my own.’

‘Luckily. I’ll leave the coffee then, I have to cut down anyway. I’ll go back upstairs.’

Elisabeth experiences panic at the thought of Coco going back upstairs. As though Coco is cycling on the other side of the Overtoom again and there’s constantly something wrong. Away with this, with this wrongness, this unseemliness. But Coco goes out of the kitchen, and each step she takes away from her she makes everything more unseemly and because ‘go away’ isn’t possible, because ‘disappear, don’t exist,’ isn’t an option for a mother, she uses words she finds ugly, Wilbert-words, Coco-words. She’s already in the hall.

‘Maybe it’s not working.’ The footsteps stop. The child understands these words. ‘Maybe it’s not working, Coco.’ Coco comes back, her expression different now. Elisabeth sits down on her rollator. Onwards now. Coco back in the kitchen. ‘It doesn’t matter if you can’t cope with me. Martin wouldn’t mind helping you move back out. I’ve already asked him.’

‘What have you already asked him?’

‘That, when, as soon as—that he. . . ’

‘You want me to leave?’

‘I want you to be happy.’ This is true. One of the things. One of the true things. Oneofthethings oneofthethings ofthethings.

Coco sits down at the kitchen table and says, ‘I want to be here.’

Buffer. The wooden buffer for the toy train. That’s what Coco’s sentence is like.

A bigger buffer now. ‘I want you to go.’ It has been said. It’s done. Don’t fight it. Failure. Now wait for the words, everything passes. Just let the story become: Things were never resolved between the mother and daughter.

Coco stays calm.

‘Go.’ Her daughter will shout in the end. Silence still. Come on.

‘I don’t have anywhere to live right now.’

What is happening? Where is the shouting, the wailing, the stamping?

‘I don’t have anywhere to live right now.’

‘Yes, that’s what you said.’

‘My room. I had to move out.’

‘You have to move out?’

‘I’m already out. I already had to leave. I told you, didn’t I? That I had to move out?’

Tumbling. Elisabeth scarcely knows what is tumbling, only that it’s tumbling. There are always abstract constructions of thoughts that she thought didn’t exist, but which suddenly can tumble and therefore do exist. Now her daughter’s dedication collapses and tumbles.

‘I did tell you, though,’ her daughter says.

Elisabeth can only nod along now and replies, ‘Yes, you said that. . . on the Overtoom.’ Because she does have a good memory. It’s just she should have thought more, made connections. It’s her own fault.

‘Where are all your things?’

‘I don’t have that much.’

‘And when did that all happen?’ Elisabeth asks, and she remembers similar sentences from years ago: And when did you see her then? And how long has it been going on?

‘Does it matter?’ her daughter asks.

‘That’s what your father said too,’ Elisabeth says.

‘Huh?’

‘“Does it matter?”. . . “It’s not about the other person. It’s about what we have. Or don’t anymore.”’

‘What are you going on about now?’

‘Oh, that whole business, back then.’

‘The divorce, you mean.’

‘Yes, that whole business with Miriam.’

‘Was he already seeing her then?’

‘That doesn’t matter. It wasn’t about that.’

‘Christ, Mum, you split up ages ago.’

‘Yes.’

‘Christ.’

‘So you had to move out, but. . . it doesn’t matter.’

‘I had to move out, yes.’

‘And you wanted to be with me.’

‘Yes.’

‘And you had to move out.’

‘Yes.’

‘But you also wanted. . . really did. . . to be with me. That’s what you wanted.’

‘I could have moved back in with Dad.’

‘And Miriam’s massage parlour then?’

‘You mean the shiatsu practice.’

She waits and then asks, ‘Is it working out for her?’ Coco says nothing. Ask again is the rule, to prove that she’s genuinely interested. Ask again, otherwise you prove to them that you’re not interested at all. That you have a good memory, but can’t remember the word ‘shiatsu’ because you don’t want to remember it. Too tired. Tumble then. Let all the interest drop too. She gets up, the question still hanging in the air: Is it working out for her?

‘I’m going for a lie-down.’ Rollator. Past the daughter.

Don’t touch her.

‘What’s the matter now?’ her daughter calls after her.

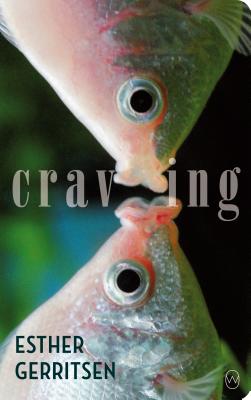

‘Very tired!’ is true. Very tired. Back to bed with her hands on her stomach, let the child swim. The little fish in her.

__________________________________

From Craving. Used with permission of World Editions. Copyright © 2018 by Esther Gerritsen. English translation copyright © 2018 by Michele Hutchison.