31 Movies Based on Short Stories

Or How to Turn a Nine-Page Story into a Feature Film

Literary adaptations have always been popular on the big screen, though every year it seems they’re more popular than ever. Most of them are based on novels, or novel series, which only makes sense—there’s often a ton of material to work with—and things usually have to be cut, but when movies are based on short stories, there’s the trickier business of expansion.

I did my best to limit this list to films truly adapted from single short stories, excluding adaptations of groups of stories (like Julieta), adaptations of full collections, and adaptations of novellas or anything else long enough to be typically published as a standalone book (other than as a film tie-in), which means you won’t see Stand By Me (a.k.a The Body) or The Shawshank Redemption (both novellas collected in King’s Different Seasons, by the way, along with Apt Pupil and The Breathing Method—adaptation coming in 2020) or Breakfast at Tiffany’s or Arrival (a.k.a. Story of Your Life) here, though they are often included in similar lists.

As a point of interest, I’ve also compared the lengths of the original short stories to the lengths of their film adaptations, and organized them from widest to least difference—but be warned that editions vary, so the page lengths listed here are from whatever book I could get my hands on (or preview online) and may not match your own version. Hopefully, they’re all at least in range.

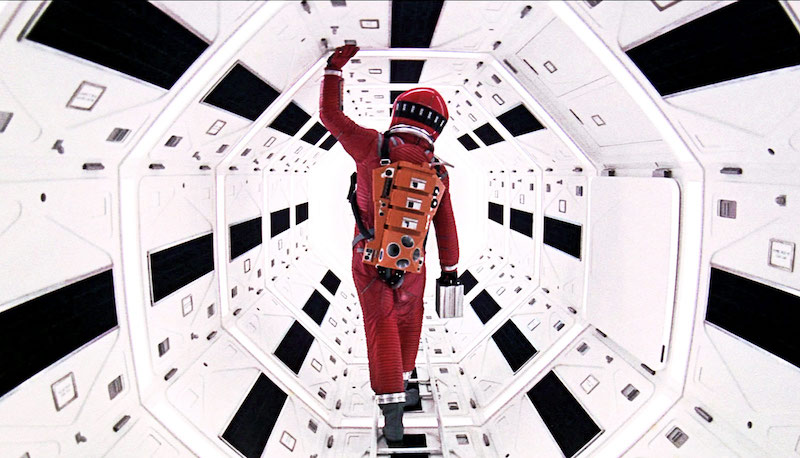

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), based on Arthur C. Clarke’s “The Sentinel” (1948), published in Ten Story Fantasy as “Sentinel of Eternity” (1951)

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), based on Arthur C. Clarke’s “The Sentinel” (1948), published in Ten Story Fantasy as “Sentinel of Eternity” (1951)

Length of short story: 8 pages

Length of film: 161 minutes

Minutes per page: 20.125

Strangely, Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick developed the film 2001: A Space Odyssey and the novel 2001: A Space Odyssey at the same time, both based in part on Clarke’s “The Sentinel,” which was originally written for a BBC contest (it was not a finalist). Though it seems Clarke would have objected to this characterization of the relationship of story to film. In a 1984 issue of Heavy Metal he wrote: “I am continually annoyed by careless references to “The Sentinel” as “the story on which 2001 is based”; it bears about as much relation to the movie as an acorn to the resultant full-grown oak. (Considerably less, in fact, because ideas from several other stories were also incorporated.) Even the elements that Stanley Kubrick and I did actually use were considerably modified.” Still, he refers to the story as “the seed from which 2001: A Space Odyssey sprang, twenty years after it was written,” so we’ll let it squeak through on a technicality.

All About Eve (1950), based on Mary Orr’s “The Wisdom of Eve,” originally published in Cosmopolitan (1946)

All About Eve (1950), based on Mary Orr’s “The Wisdom of Eve,” originally published in Cosmopolitan (1946)

Length of short story: 9 pages

Length of film: 138 minutes

Minutes per page: 15.3

In the mid-40s, Mary Orr, then a young actress, sold a short story (based on a true story apparently related to her by the actress Elisabeth Bergner, whose assistant tried to steal her career) to Cosmopolitan for $800. It was optioned by Twentieth Century Fox for about $5,000 and was eventually developed into a screenplay written by Joe Mankiewicz, who, according to Sam Staggs, writing about the film in Vanity Fair, “kept not a line of dialogue from Mary Orr’s story, but he did retain what served him better: the breezy, brittle tone.” It worked. In 1950, All About Eve won six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Screenplay.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), based on Brian Aldiss’s “Supertoys Last All Summer Long,” originally published in Harper’s Bazaar (1969)

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), based on Brian Aldiss’s “Supertoys Last All Summer Long,” originally published in Harper’s Bazaar (1969)

Length of short story: 11 pages

Length of film: 146 minutes

Minutes per page: 13.27

Aldiss’s story was originally optioned by Stanley Kubrick in 1982, and the two worked together for years to develop the project, but they clashed on the ultimate vision. In an introduction to a 2001 edition of his collection, Aldiss described the challenges of adapting his story at all—at first, he says he couldn’t see his “vignette” as a feature film—and working with Kubrick: “He would never half accept anything, turn it around, see if there was not some merit in it. While this was the sign of a clear sighted man, perhaps there was also a weakness in the approach.” Kubrick gave Aldiss a copy of the story of Pinocchio, but Aldiss “could not or would not see the parallels.” But Kubrick saw the parallels: he wanted the android child to become human, and he also wanted a Blue Fairy. Even more troubling, he wanted to cast a real android in the part. “I tried to persuade Stanley that he should create a great modern myth to rival Dr. Strangelove and 2001, and to avoid fairy tale,” Aldiss wrote. “It was absurd of me. I was wheeled out of the picture.”

The movie was never made, and after Kubrick’s death, his friend Steven Spielberg took up the project. By then, Aldiss had written two more stories in the same world as the first, and Spielberg bought them and made A.I. Fittingly, some have considered the final movie, released almost 20 years after Kubrick optioned it, as a self-conscious ode to the director, noting some visual similarities between it and the rest of Kubrick’s oeuvre.

Jindabyne (2006), based on Raymond Carver’s “So Much Water So Close to Home,” published in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981)

Jindabyne (2006), based on Raymond Carver’s “So Much Water So Close to Home,” published in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981)

Length of short story: 10 pages

Length of film: 123 minutes

Minutes per page: 12.3

Before this story was a film, it was a rock album—released by the Australian band Paul Kelly and the Messengers in 1989, a year after Carver’s death. Well, the album is called So Much Water So Close to Home, but it’s technically only one song, “Everything’s Turning to White” that is based on the Carver story in question, in which a woman begins to identify with the corpse her husband and his friends found on a fishing trip and failed to report for several days. Paul Kelly would go on to co-write the score for Jindabyne, making him probably the biggest fan of this story in the world (or at least in Australia).

Everything Must Go (2010), based on Raymond Carver’s “Why Don’t You Dance?,” published in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981)

Everything Must Go (2010), based on Raymond Carver’s “Why Don’t You Dance?,” published in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981)

Length of short story: 8 pages

Length of film: 97 minutes

Minutes per page: 12.125

Technically, this story was first adapted as a short film, the award-winning Everything Goes (starring Hugo Weaving and Abbie Cornish, no less). Its incarnation as a feature had a more middling reception (Will Ferrell as a Carver hero? I don’t know), but Roger Ebert thought it was pretty good. “Carver was an alcoholic who lost most of the things in his life and then found them again through recovery and the love of his wife, the poet Tess Gallagher,” he wrote in a review of the film. “In his story, the hero simply has a sale to sell everything he owns, which as we all know is better than dealing with the movers. In the film, the (never seen) wife is the deciding factor, but as the days and nights slide past, Nick gradually clears out not only his valued possessions but his excess inventory. . . . The movie doesn’t trick up this story much more than it needs. The spartan solemnity of the Carver story seems buried within it.”

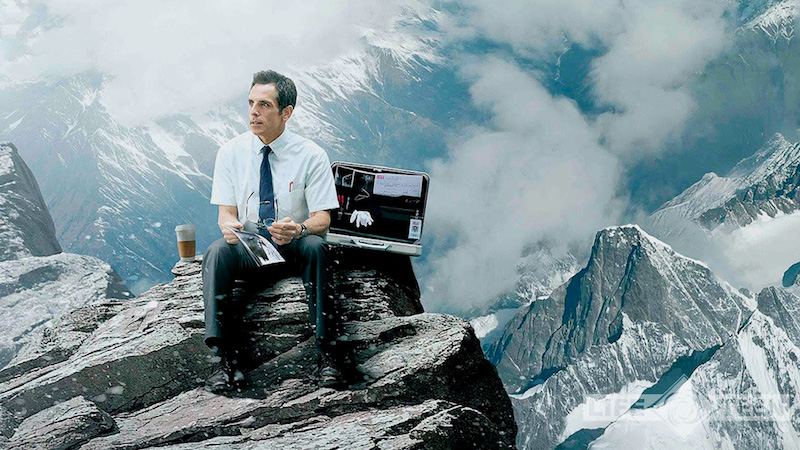

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013), based on James Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” originally published in The New Yorker (1939)

Length of short story: 10 pages

Length of film: 114 minutes

Minutes per page: 11.4

This is actually the second film adaptation of Thurber’s beloved and very short story about a daydreaming everyman, after one in 1947 which Thurber, despite being consulted on, wound up hating. This one finally came to fruition after almost 20 years of development hell, with Jim Carey, Owen Wilson, Zach Braff, and Sacha Baron Cohen all attached at one point or another. Like the first version, it is quite different from the original story.

The Swimmer (1968), based on John Cheever’s “The Swimmer,” originally published in The New Yorker (1964)

The Swimmer (1968), based on John Cheever’s “The Swimmer,” originally published in The New Yorker (1964)

Length of short story: 9 pages

Length of film: 95 minutes

Minutes per page: 10.5

It’s hard to imagine how this short story—lovely, elegiac, and ultimately surrealist—could have been made into a film, but turns out the film is much the same, if rather stretched (ten minutes per page!). Roger Ebert called it “a strange, stylized work, a brilliant and disturbing one,” and also noted:

The Swimmer is based on a John Cheever story from the New Yorker, and it’s the sort of allegory the New Yorker favors. Like assorted characters by John Updike and J.D. Salinger, Cheever’s swimmer is a tragic hero disguised as an upper-class suburbanite. There are a lot of tragic heroes hidden in suburbia, I guess, perhaps because so many of them subscribe to the New Yorker. You are what you read.

Harsh but fair. After all, the film’s original posters read: “When you talk about The Swimmer will you talk about yourself?”

The Killers (1946), and The Killers (1964) based on Ernest Hemingway’s “The Killers,” originally published in Scribner’s Magazine (1927)

The Killers (1946), and The Killers (1964) based on Ernest Hemingway’s “The Killers,” originally published in Scribner’s Magazine (1927)

Length of short story: 11 pages

Length of film: 103 minutes (1946), 95 minutes (1964)

Minutes per page: 9.36 (1946), 8.63 (1964)

“That story probably had more left out of it than anything I ever wrote,” Hemingway famously said about this widely anthologized story. “I left out all Chicago, which is hard to do in 2951 words.” It’s also very few words to turn into a feature film, but that hasn’t stopped Hollywood from making two (plus a short film by Andrei Tarkovsky, no less). The 1946 adaptation stars Burt Lancaster and Ava Gardner, and the 1964 adaptation features Lee Marvin, John Cassavetes, Angie Dickinson and (fun fact!) Ronald Reagan in his last film role.

Secretary (2002), based on Mary Gaitskill’s “Secretary,” from Bad Behavior (1989)

Secretary (2002), based on Mary Gaitskill’s “Secretary,” from Bad Behavior (1989)

Length of short story: 15 pages

Length of film: 111 minutes

Minutes per page: 7.4

This adaptation of one of the darkest stories in a very dark (and very good) collection takes an unbelievably happy turn at the end—a relief, in one sense, but doesn’t exactly make for a faithful adaptation.

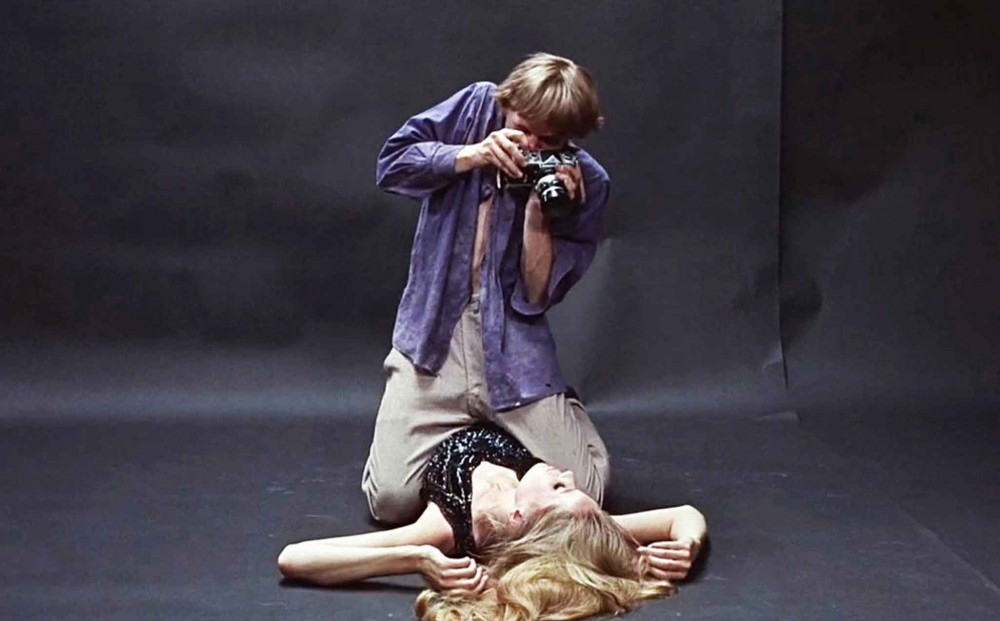

Blow-Up (1966), based on Julio Cortázar’s “Las babas del diablo” (“The Devil’s Drool”) (1959), published in End of the Game and Other Stories, tr. Paul Blackburn (1967)

Blow-Up (1966), based on Julio Cortázar’s “Las babas del diablo” (“The Devil’s Drool”) (1959), published in End of the Game and Other Stories, tr. Paul Blackburn (1967)

Length of short story: 16 pages

Length of film: 111 minutes

Minutes per page: 6.94

In his introduction to the Everyman Library collection of Cortázar’s work, Ilan Stavans called it “arguably the most challenging of Cortázar’s stories, and perhaps the most rewarding . . . It is a narrative told in the first, second, and third person, all at once, a story about the quest to tell a story that can’t really be articulated in sequential, coherent fashion: a story about the defeat of literature.” Michelangelo Antonioni’s adaptation stars Vanessa Redgrave and David Hemmings and was a sensation upon its release—not only “for its frank view of sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll in swinging London,” as one writer put it, but because it grossed over 10 times was it cost and thereby “helped liberate Hollywood from its puritanical prurience.”

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008), based on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” originally published in Collier’s (1922)

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008), based on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” originally published in Collier’s (1922)

Length of short story: 26 pages

Length of film: 166 minutes

Minutes per page: 6.38

You already know all about this horror movie, I presume. More interesting is the Cambridge edition of Tales of the Jazz Age, which includes Fitzgerald’s brief commentary on the story. It was inspired, he writes, “by a remark of Mark Twain’s to the effect that it was a pity that the best part of life came at the beginning and the worst part at the end. By trying the experiment upon only one man in a perfectly normal world I have scarcely given his idea a fair trial. Several weeks after completing it, I discovered an almost identical plot in Samuel Butler’s Note-books.” He goes on to quote a letter he received after the story’s original publication from “an anonymous admirer in Cincinnati”:

Sir—

I have read the story Benjamin Button in Colliers and I wish to say that as a short story writer you would make a good lunatic I have seen many peices of cheese in my life but of all of the peices of cheese I have ever seen you are the biggest peice. I hate to waste a peice of stationary on you but I will.” [sic x 4]

Rashomon (1950), based on Ryūnosuke Akutagawa’s “In a Grove,” originally published in Shinchō (1922)

Rashomon (1950), based on Ryūnosuke Akutagawa’s “In a Grove,” originally published in Shinchō (1922)

Length of short story: 14 pages

Length of film: 88 minutes

Minutes per page: 6.28

Fun fact: the title of Kurosawa’s classic is taken from Akutagawa’s story of the same name, along with a few details from the framing narrative—but the bulk of the film, including the plot and the form, was actually adapted from a different Akutagawa, “In a Grove.”

Total Recall (1990), and Total Recall (2012) based on Philip K. Dick’s “We Can Remember it For You Wholesale,” originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (1966

Total Recall (1990), and Total Recall (2012) based on Philip K. Dick’s “We Can Remember it For You Wholesale,” originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (1966

Length of short story: 18 pages

Length of film: 113 minutes (1990), 118 minutes (2012), 130 minutes (2012 extended director’s cut)

Minutes per page: 6.27 (1990), 6.5 (2012), 7.2 (2012 extended director’s cut)

It took about a decade for Total Recall to come together. Somewhere in there, David Cronenberg was attached to direct. “I worked on it for a year and did about 12 drafts,” Cronenberg told WIRED. “Eventually we got to a point where Ron Shusett said, ‘You know what you’ve done? You’ve done the Philip K. Dick version.’ I said, ‘Isn’t that what we’re supposed to be doing?’ He said, ‘No, no, we want to do Raiders of the Lost Ark Go to Mars.'” A few changes later—it was going to be Swayze, not Schwarzenegger—and the movie was made. It was a huge hit. “The whole phenomenon of Philip K. Dick short stories selling for a lot of money started with Total Recall,” Dick’s agent Russell Galen said.

In the Bedroom (2001), based on Andre Dubus’s “Killings,” originally published in The Sewanee Review (1979)

In the Bedroom (2001), based on Andre Dubus’s “Killings,” originally published in The Sewanee Review (1979)

Length of short story: 21 pages

Length of film: 131 pages

Minutes per page: 6.24

A harrowing story about a man looking for revenge after his son’s murder becomes an equally harrowing film in Todd Field’s hands. When asked in a 1993 interview with Olivia Carr Edenfield whether his use of water in “Killings” was symbolic, Dubus said:

Let me give you a message. He didn’t get his life back. He violated nature. He’s out in the Neverland. I only use water in that story because the actual location of the story is a real place I can write about. It seemed an obvious place to bury a body and dispose of a gun. It’s called “Killings” because everybody is getting killed in that story. He doesn’t gain his life; he does something terrible. Of course, I didn’t know that he would do it. . . . I put the water there because they drove along the river there. That wasn’t symbolic. I’ve never that I can recall in my life used water as a symbol. I refuse to see Frederic Henry [in A Farewell to Arms] swimming across the river to get away from the war as a baptism either; it looks like a pretty good escape route.

In the Bedroom was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and Best Writing for a Screenplay Based on Previously Published Material.

3:10 to Yuma (1957) and 3:10 to Yuma (2007), based on Elmore Leonard’s “Three-Ten to Yuma,” originally published in Dime Western Magazine (1953)

3:10 to Yuma (1957) and 3:10 to Yuma (2007), based on Elmore Leonard’s “Three-Ten to Yuma,” originally published in Dime Western Magazine (1953)

Length of short story: 15 pages

Length of film: 92 minutes (1957), 122 minutes (2007)

Minutes per page: 6.13 (1957), 8.13 (2007)

A good old Western with a good old ticking clock: that 3:10 train to Yuma, which needs to leave with a certain outlaw on it. In the original story, a deputy sheriff agrees to keep a prisoner in a hotel room until the appointed time, risking his life against the baddie’s gang. “The question of why the deputy risks his life for the paltry sum of $150 a month goes unanswered,” Kent Jones wrote in a 2013 appreciation of the film. “Leonard himself was initially disappointed that it did not remain so in the film version. This would have been a tall order: the mystery of the deputy’s motivation is made possible by the intense narrative compression of the story and would have been difficult to sustain throughout a feature-length running time.” Ultimately though, Leonard was pleased, and ranked it among the best adaptations of his work, and audiences were pleased enough to warrant a second attempt, with Russell Crowe and Christian Bale.

The Last Time I Saw Paris (1954), based on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Babylon Revisited,” originally published in the Saturday Evening Post (1931)

The Last Time I Saw Paris (1954), based on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Babylon Revisited,” originally published in the Saturday Evening Post (1931)

Length of short story: 21 pages

Length of film: 116 minutes

Minutes per page: 5.52

At least one reviewer in 1954 was not impressed by the translation of Fitzgerald’s semi-autobiographical story to film:

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s poignant story of a father’s lonely love for his little girl, told in “Babylon Revisited,” has “inspired” Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s big color film, The Last Time I Saw Paris, which opened last night at the Capitol. “Inspired” is a polite way to put it. For what has actually occurred is that Mr. Fitzgerald’s cryptic story of a man’s return to the scene of his wantonness—to Paris, that is—in the tense hope of recovering his child by his late wife has excited the picture-makers to an orgy of turning up the past and constructing a whole lurid flashback on the loving and lushing of the man and his wife before she died. Where Fitzgerald did it in a few words—in a few subtle phrases that evoked a reckless era of golden dissipation toward the end of the Twenties’ boom—Richard Brooks, who directed this picture after polishing up an Epstein-brothers’ script, has done it in a nigh two-hour assembly of bistro balderdash and lush, romantic scenes.

Ouch.

The Illusionist (2006), based on Steven Millhauser’s “Eisenheim the Illusionist,” published in The Barnum Museum (1990)

The Illusionist (2006), based on Steven Millhauser’s “Eisenheim the Illusionist,” published in The Barnum Museum (1990)

Length of short story: 22 pages

Length of film: 110 minutes

Minutes per page: 5

I’m always shocked that more of Millhauser’s short stories haven’t been adapted to screen—I had thought this was the only one, in fact, but turns out there was another, in 2014: The Sisterhood of Night. It looks . . . not great. Do better by this American master, please, Hollywood.

Minority Report (2002), based on Philip K. Dick’s “The Minority Report,” originally published in Fantastic Universe (1956)

Minority Report (2002), based on Philip K. Dick’s “The Minority Report,” originally published in Fantastic Universe (1956)

Length of short story: 32 pages

Length of film: 145 minutes

Minutes per page: 4.53

Originally conceived of as a sequel to Total Recall, but now a Tom Cruise classic. Apparently, director Paul Verhoeven “envisioned Total Recall II: The Minority Report as a whiz-bang, action-packed, “theological-philosophical challenge” to the Calvinist concept of predestination.” This project also had a few hills to climb before it came together, and when it did, it was pretty dissimilar to the original story. “It’s very difficult to be true to Phil Dick and make a Hollywood movie,” screenwriter Gary Goldman told WIRED. “His thinking was subversive. He questioned everything Hollywood wanted to affirm.” Which didn’t stop Hollywood from making several more adaptations of Dick’s stories—but I’m going to stop here. There are several more I could include—The Adjustment Bureau, Next, Paycheck, etc—but I think I’ve hit the most important ones.

Brokeback Mountain (2005), based on Annie Proulx’s “Brokeback Mountain,” originally published in The New Yorker (1997)

Brokeback Mountain (2005), based on Annie Proulx’s “Brokeback Mountain,” originally published in The New Yorker (1997)

Length of short story: 30 pages

Length of film: 134 minutes

Minutes per page: 4.46

Certainly one of the most successful short story to film adaptations—or at least successful enough that Annie Proulx grew to resent it deeply. “People saw it as a story about two cowboys,” she said in 2009. “It was never about two cowboys. You know you have to have characters to hang the story on but I guess they were too real. A lot of people have adopted them and put their names on their license plates. Sometimes the cart gets away from the horse—the characters outgrew the intent.”

The Fallen Idol (1948), based on Graham Greene’s “The Basement Room” (1936)

The Fallen Idol (1948), based on Graham Greene’s “The Basement Room” (1936)

Length of short story: 22 pages

Length of film: 95 minutes

Minutes per page: 4.32

According to David Lodge, writing in the Guardian, The Fallen Idol was Graham Greene’s favorite film adaptation of his own work—even rating it above The Third Man, which was also directed by Carol Reed, because “it was more, I felt, a writer’s film, and The Third Man more a director’s film.” Lodge calls the film “a model of what the development of a movie should be, but very seldom is: a close collaboration between a writer and a director who enjoyed complete rapport, supported by a producer (Alexander Korda) who did not interfere with the creative process.” Still, when Greene was originally approached about an adaptation, he had his doubts: “It seemed to me that the subject was unfilmable,” he said.

A murder committed by the most sympathetic character and an unhappy ending which would certainly have imperilled the £250,000 that films nowadays cost. However, we went ahead, and in the conferences that ensued the story was quietly changed, so that the subject no longer concerned a small boy who unwittingly betrayed his best friend to the police, but dealt instead with a small boy who believed that his friend was a murderer and nearly procured his arrest by telling lies in his defense.

In the end, and after many changes, the film was a success, and Greene was nominated for an Academy Award for his screenplay adapting his own story, which you can read in Zoetrope.

Johnny Mnemonic (1995), based on William Gibson’s “Johnny Mnemonic,” originally published in Omni (1981)

Johnny Mnemonic (1995), based on William Gibson’s “Johnny Mnemonic,” originally published in Omni (1981)

Length of short story: 23 pages

Length of film: 96 minutes

Minutes per page: 4.17

Few things are more delicious than classic ’90s Keanu Reeves trash. Or more disgusting, depending on your temperament. Gibson himself wrote the screenplay for the adaptation, but the film came out a lot different from the original text, and a lot different than he had intended. “I wanted [Johnny Mnemonic] to be like all of the really great moments in all of the really bad science fiction movies that I’ve watched over the years,” Gibson said in a 1998 interview. “A dangerous strategy. . . . Basically what happened was it was taken away and re-cut by the American distributor in the last month of its prerelease life, and it went from being a very funny, very alternative piece of work to being something that had been very unsuccessfully chopped and cut into something more mainstream.” Oh, for the Johnny Mnemonic we might have known!

By the way, after the film was released, Terry Bisson wrote a novelization out of the screenplay that was published separately under the same title, and if you think a novelization of a movie based on a short story sounds ridiculous, then you really haven’t seen this film.

Sleepy Hollow (1999), based on Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” originally published in The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. (1820)

Sleepy Hollow (1999), based on Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” originally published in The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. (1820)

Length of short story: 33 pages

Length of film: 105 minutes

Minutes per page: 3.18

There are a million and one adaptations of this classic short story across media, so in the interest of not losing my head (ha ha), I’ll just mention the most famous one, the middling Tim Burton movie (that nonetheless won an Academy Award for Art Direction) in which Christina Ricci is inexplicably blonde, Johnny Depp has Cool Goggles, and Christopher Walken needs serious dental work. A loose adaptation of the original story, to be sure—but aren’t they all.

Smooth Talk (1985), based on Joyce Carol Oates’s “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?,” originally published in Epoch (1966)

Smooth Talk (1985), based on Joyce Carol Oates’s “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?,” originally published in Epoch (1966)

Length of short story: 32 pages

Length of film: 96 minutes

Minutes per page: 3

In an essay about the adaptation of her most anthologized work, Joyce Carol Oates mostly praises director Joyce Chopra and screenwriter Tom Cole’s work—”they were required to do a good deal of filling in, expanding, inventing,” she writes, “Connie’s story becomes lavishly, and lovingly, textured”—as well as the acting chops of both Laura Dern and Treat Williams.

My difficulties with Smooth Talk have primarily to do with my chronic hesitation—about seeing/hearing work of mine abstracted from its contexture of language. All writers know that Language is their subject; quirky word choices, patterns of rhythm, enigmatic pauses, punctuation marks. Where the quick scanner sees “quick” writing, the writer conceals nine tenths of the iceberg. Of course we all have “real” subjects, and we will fight to the death to defend those subjects, but beneath the tale-telling it is the tale-telling that grips us so very fiercely. The writer works in a single dimension, the director works in three. I assume they are professionals to their fingertips; authorities in their medium as I am an authority (if I am) in mine. I would fiercely defend the placement of a semicolon in one of my novels but I would probably have deferred in the end to Joyce Chopra’s decision to reverse the story’s conclusion, turn it upside down, in a sense, so that the film ends not with death, not with a sleepwalker’s crossing over to her fate, but upon a scene of reconciliation, rejuvenation.

A girl’s loss of virginity, bittersweet but not necessarily tragic. Not today. A girl’s coming-of-age that involves her succumbing to, but then rejecting, the “trashy dreams” of her pop teenage culture. “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” defines itself as allegorical in its conclusion: Death and Death’s chariot (a funky souped-up convertible) have come for the Maiden. Awakening is, in the story’s final lines, moving out into the sunlight where Arnold Friend waits:

“My sweet little blue-eyed girl,” he said in a half-sung sigh that had nothing to do with [Connie’s] brown eyes but was taken up just the same by the vast sunlit reaches of the land behind him and on all sides of him—so much land that Connie had never seen before and did not recognize except to know that she was going to it.

—a conclusion impossible to transfigure into film.

Fair enough.

A Face in the Crowd (1957), based on Budd Schulberg’s “Your Arkansas Traveler,” published in Some Faces in the Crowd (1953)

A Face in the Crowd (1957), based on Budd Schulberg’s “Your Arkansas Traveler,” published in Some Faces in the Crowd (1953)

Length of short story: 42 pages

Length of film: 125 minutes

Minutes per page: 2.98

Schulberg wrote the screenplay for A Face in the Crowd based on his own short story, the opener to his 1953 collection. Directed by Elia Kazan, it was the film that launched Andy Griffith’s career—and also one that’s been getting mentioned a lot lately, concerning as it does a charismatic drifter who cons his way into national TV stardom. Last year, Dan Piepenbring called it “a film so perfectly suited for our moment that a toothless, vacuous remake must surely be on the lips of studio execs as I write this,” and points out the original poster, which reads: “Power! He loved it! He took it raw in big gulpfuls . . . He liked the taste, the way it mixed with the bourbon and the sin in his blood!” He’s not the only one who has connected it to Trump, either, but don’t let that put you off—it’s a great film, and in 2008 was entered into the National Film Registry.

The Fly (1958) and The Fly (1986), based on George Langelaan’s “The Fly,” originally published in Playboy (1957)

The Fly (1958) and The Fly (1986), based on George Langelaan’s “The Fly,” originally published in Playboy (1957)

Length of short story: 32 pages (estimated based on my count of 12,377 words)

Length of film: 94 minutes (1958), 96 minutes (1986)

Minutes per page: 2.94 (1958), 3 (1986)

You don’t really think of body horror being based on literary fiction, but hey, that’s Cronenberg for you. Langelaan’s story won Playboy‘s award for Best Fiction of the year before being adapted for the first time, and was also adapted into an opera in 2008.

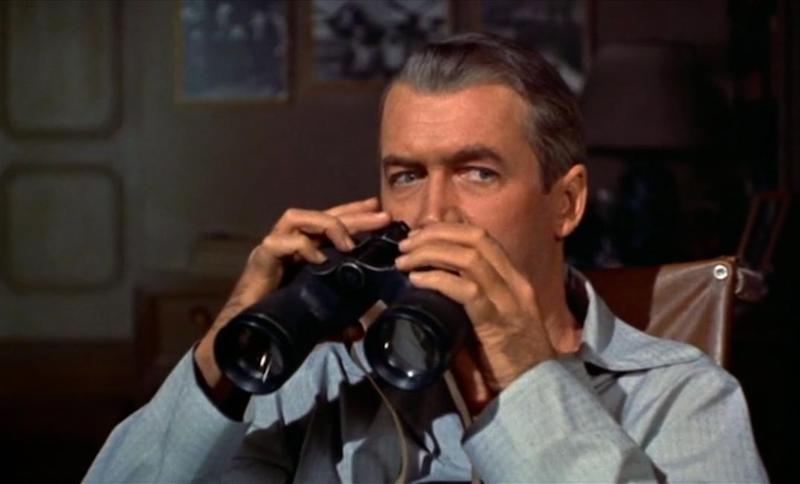

Rear Window (1954), based on Cornell Woolrich’s “It Had to Be Murder,” originally published in Dime Detective Magazine (February 1942)

Rear Window (1954), based on Cornell Woolrich’s “It Had to Be Murder,” originally published in Dime Detective Magazine (February 1942)

Length of short story: 40 pages

Length of film: 112 minutes

Minutes per page: 2.8

Fun fact: Hitchcock’s classic film is based on Cornell Woolrich’s “It Had to Be Murder” (which Woolrich first published under the name “William Irish”), which is itself based on another short story: H. G. Wells’ “Through a Window” (1894).

Away From Her (2007), based on Alice Munro’s “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” originally published in The New Yorker (1999)

Away From Her (2007), based on Alice Munro’s “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” originally published in The New Yorker (1999)

Length of short story: 42 pages

Length of film: 110 minutes

Minutes per page: 2.62

It’s always tricky to adapt something that’s already pretty perfect into something else that’s any good, but first-time director Sarah Polley did it well here, and the film has achieved universal acclaim, especially in Canada, where Alice Munro is kind of a saint. As she well should be.

The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962), based on Alan Sillitoe’s “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner,” published in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner (1959)

The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962), based on Alan Sillitoe’s “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner,” published in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner (1959)

Length of short story: 48 pages

Length of film: 104 minutes

Minutes per page: 2.16

Well, at least someone knows a good title when they see it. Sillitoe—one of the literary “angry young men” of the 1950s, like Kinglsey Amis and John Osborne—adapted the screenplay for this film from his own short story, in which a troubled and rebellious young man finds a kind of solace in running. Oddly, the film and story have been very popular with bands, several of whom, including Belle & Sebastian, Iron Maiden, Chumbawamba, Fugazi, have borrowed elements in their own titles and songwriting.

Don’t Look Now (1973), based on Daphne du Maurier’s “Don’t Look Now,” originally published in Not After Midnight (1971)

Don’t Look Now (1973), based on Daphne du Maurier’s “Don’t Look Now,” originally published in Not After Midnight (1971)

Length of short story: 56 pages

Length of film: 110 minutes

Minutes per page: 1.96

Pauline Kael called this film, which opened to mixed reviews but is now considered a cult horror classic, “the fanciest, most carefully assembled enigma yet put on the screen. Nicolas Roeg is a chillingly chic director; the picture is an example of high-fashion gothic sensibility. . . . Using du Maurier as a base, Roeg comes closer to getting Borges on the screen than those who have tried it directly, but there’s a distasteful clamminess about the picture. Roeg’s style is in love with disintegration.”

Of course, in the Daphne du Maurier department, there’s also “The Birds,” which Hitchcock made famous—but I’ll just assume you already know about that one.

The Dead (1987), based on James Joyce’s “The Dead,” published in Dubliners (1914)

The Dead (1987), based on James Joyce’s “The Dead,” published in Dubliners (1914)

Length of short story: 43 pages

Length of film: 83 minutes

Minutes per page: 1.93

Almost certainly Joyce’s most taught work, “The Dead” is also among his best, and The Dead is among John Huston’s best too. As Nick Laird put it in The Guardian, the tagline for the movie “is: “A vast, merry, and uncommon tale of love.” Well, it’s neither vast nor merry, but the uncommon tale makes an uncommon, and uncommonly good, movie. . . . Using a screenplay written by his son Tony, Huston managed to create something worthy of Joyce’s masterwork, and not simply by being faithful.” The camerawork, the acting, and the directing make it something special.

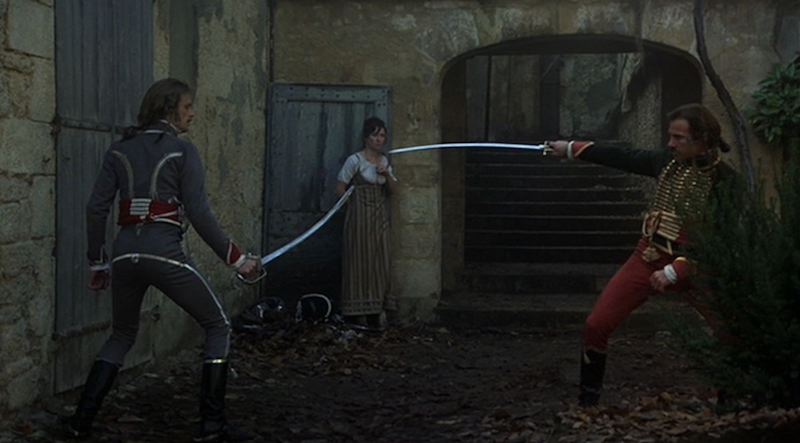

The Duellists (1977), based on Joseph Conrad’s “The Duel,” published in A Set of Six (1908)

The Duellists (1977), based on Joseph Conrad’s “The Duel,” published in A Set of Six (1908)

Length of short story: 130 pages

Length of film: 100 minutes

Minutes per page: .77

Fun fact: this adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s “The Duel” (sometimes titled “Point of Honor”), was Ridley Scott’s first ever feature film, and it won the prize for best debut at Cannes that year. The tagline is: “Fencing is a science. Loving is a passion. Duelling is an obsession.” Ok!