Craig Davidson on the Secrets Best Left Out of Memoir

"I’d slipped a gear between living a story and making a story."

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

In my early thirties I spent a year driving a bus for children who had, as the nomenclature held at the time, special needs. One of the boys on my bus had been the victim of a tragic hit-and-run. He and his mother were out for a walk—the boy was in his wheelchair—and a drunk driver hit them. The boy’s injuries necessitated a medical coma, while his mother died on impact.

Three years later, looking to write about that boy, I sat with my messy notes—jotted on Post-Its, back pages ripped out of old paperbacks, yellow foolscap, even wrinkled gum wrappers—and found a tape I’d recorded the night I’d decided to confront the man who’d irrevocably changed the boy’s life.

The man’s actions over the course of that fateful afternoon were a matter of public record. The papers detailed the bars he’d drunk at, his meandering path home. I decided to retrace his steps: to go to those dismal bars, drink what he drank, eventually shamble up to his door… and knock.

I set off on a Friday afternoon, cabbing it from joint to joint. I had a Sony M430 Dictaphone, with the microcassettes, into which I hissed my increasingly drunken and disjointed thoughts. Evil, fate, guilt and punishment. How the world failed to cohere or make rational sense—because here was this man under house arrest, allowed to attend his daughter’s soccer games once a week, while the boy’s family was shattered.

I staggered from the final bar, towards confrontation. But the tape holds no record of that, as it never occurred.

It’s not that I lost my nerve, though the worthiness of the plan did dwindle as my intoxication skyrocketed. It was that I realized I’d slipped a gear between living a story and making a story.

One of the most dangerous traps a memoirist can fall into is the sense that their story isn’t enough. Instead of faithfully recording, the urge comes to sweeten events, even fabricate them, or—my failing—to rig them, ginning up confrontations or emotional highs and lows. I found myself doing so with all the raven-eyed avidity of a reality TV producer. When a writer mines their life for story, they must avoid the urge to summon veins of gold where none exist.

I now cringe at my craven desire for extra—for the addition of something poignant, or hilarious, or profound, rather than the quotidian and human things we all say and do. This hope that events might magically spiral towards epiphany or grace. I occasionally caught myself stage-managing my interactions like an overwrought theater director: energy UP, eyes UP, smiles UP, everything UP!

None of the slurred, wild-eyed contents of that microcassette ever made it into the book I wrote about my year driving that bus … but it dogs me to this day what did make it in. Some confidences—some secrets—ought to be kept close to the listener’s heart. They belong to nobody but the teller and the listener. The listener has a duty to keep it so.

There’s a fine, gauzy line. Between the life we live as writers and the life we think others would want to read about. Between the stories we feel entitled to tell seeing as they’re our own lived experience and those that are part of a communal experience … who owns those? Who has the right to tell them? Does anyone?

The rest of my life I’m going to wonder this.

*

Read more on writing memoir:

T Kira Madden on why memoirs are not “cathartic” for writers.

Melissa Stephenson on using notecards to write a memoir.

Neal Thompson on talking to his family about his memoir.

Chavisa Woods on documenting sexism and harassment.

*

3 Well-Crafted Memoirs

RECOMMENDED BY CRAIG DAVIDSON

Tobias Wolff, This Boy’s Life

Mary Karr, Lit

Russell Wangersky, Burning Down the House

__________________________________

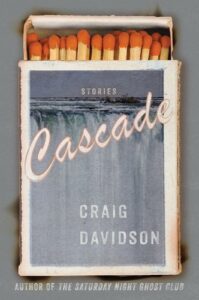

Cascade by Craig Davidson is available via W. W. Norton & Company.

Craig Davidson

Craig Davidson was born and grew up in St. Catharines, Ontario, near Niagara Falls. He has published three previous books of literary fiction: Rust and Bone, which was made into an Oscar-nominated feature film of the same name, The Fighter, and Sarah Court. Davidson is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and his articles and journalism have been published in the National Post, Esquire, GQ, The Walrus, and The Washington Post, among other places. He is the author of The Saturday Night Ghost Club and Precious Cargo. He lives in Toronto, Canada.