Crafting a Documentary Poetics of Resistance in the Shadow of State Violence

“In situations in which the story of people is being smothered by institutions of power, adversarial documents can provide an opening.”

On. Off. On. Off. I flicked the light switches. Stared at the flush of the toilet. Traced the exposed brick stairwell, and let the dust dress my finger, like my home was the moon. There are no poetics yet in this story.

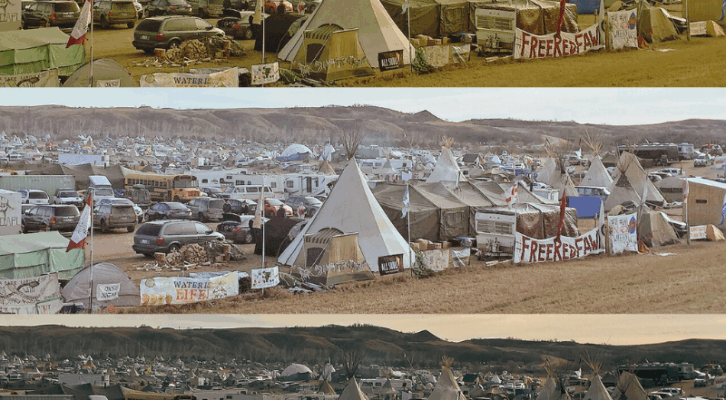

I was back in St Louis, home from the Oceti Sakowin Camp at Standing Rock, where I’d been given the gift of being a guest in the Lakhota and Indigenous-led Water Protector Movement. I supported Alayna Eagle Shield, who founded a school, or rather a place of community and movement-based learning, for the kids who lived there full time. The camp was something beautiful blooming in defiance of colonialism, which is to say, in love, in relationship.

How else could we live here, on the prairie, in this multi-generational space, without taking care of each other—without someone willing to chop wood, someone willing to stay up late to feed the fire, someone cutting a hundred onions and someone else stirring them into a pot as big as a child’s bicycle? Have you ever gone into a porta-potty and found it squeaky clean and smelling of lemon? That’s what community love feels like.

I wasn’t sure what of the story I could tell—but I knew that I had things to say in response to this looking glass world the state was creating.

The camp was also the site of intense state violence. Where private security aimed aggressive dogs at the body of women. Where police threw grandmothers to the ground. Where phones were tapped. Where documents were stolen from the school. Where, as the prairie chilled, tear gas and water cannons became an expected way for the state to interrupt prayer.

And then, my back gave out, winter felt like a fist, and suddenly, I was home in St Louis. I needed surgery and couldn’t return to the last vestiges of camp. I was lucky, I knew. I was safe. But, home was whiplash, or maybe, rather, home was the set of a childhood tv show. Familiar, but perhaps not quite mine? (There are still no poetics here).

And, I couldn’t even think about camp. My brain threw sandbags against the story, did her best to keep it away from me. Any fragile ability I had to pretend I knew who I was felt like it would be bowled over by remembering. But, if I couldn’t fully inhabit my life—couldn’t reconcile it as mine—how could I live? How could I figure out what was next?

I knew that writing, as it always had been, would need to be part of this reconciling. But I didn’t feel ready to open the gates to the intensity of the experience. I didn’t know what parts of this felt right, as a white woman, to share. Plus, everything I read or heard or saw about camp from the media felt off-kilter and like it missed the core truth in the story—the love, the care. How could I begin to counteract that? The starting line for healing, for writing, was not visible from my bed, from doctor’s appointments, from my deep numbness.

And then, in that anesthetized winter and spring, as I tried to do what my doctors called “recover,” I happened to read several amazing books that used documents. Solmaz Sharif’s LOOK, Tyehimba Jess’s Olio, Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas. Of course, I had read poems that used documents before—but these all held such an intense poetic bravery. They didn’t confine themselves to one method of document use, but rather did whatever was necessary to tell the story. Broke them apart and reassembled them new. Gave them new voice. Pried them open until the voices of communities could speak through them.

Then, a friend sent me a report released by the police—just to show me how wildly off-base the narrative was. I began looking at official reports from the camp. I didn’t know how to think about my experiences generally, but became obsessed with these missives. I printed them all out and put them in a lime green folder and started reading each and every one.

In these reports, I would see a story not just that I understood as false (though it very much often was) but more like someone had thrown my experience in the blender of another dimension. Nearly unrecognizable. Beneath these documents, though, I would see a shimmer. Some glimpse of the people I loved. The camp that had been my home. The powerful Indigenous resistance I had been a guest in. This story of the police reports was the story of Whiteness, of colonial power. But that wasn’t the only story.

Even though I didn’t quite feel ready to write poems, I started to experiment, cautiously, with the documents, like dipping a toe into the bathtub to check the temperature. I wasn’t sure what of the story I could tell—but I knew that I had things to say in response to this looking glass world the state was creating. And I knew that if I was going to wrestle with my own whiteness in this space—I needed to wrestle also with the story Whiteness was telling.

I found that the story of the camp knew how to pry apart the cracks. Knew how to grow something more true and more beautiful.

So, I started trying to contend with the documents. The first poem I wrote (which didn’t make it into the book) used a document about a very violent day—in which private security forces unleashed dogs onto peaceful Water Protectors. And yet, when I looked at the text—where were the women who lay down in the path of the bulldozers, their bright skirts like prairie flowers? Where was the triumphant Water Protector on his horse at the top of the mound of churned and desecrated soil? Where were the burial sites? The woman clutching the dog bite on her breast? I tried to tell what I had seen with just the words in the document—and when the story absolutely required a word the document didn’t have (land, attack, sacred, bite, women, Water Protector)—I left a blank.

I started next on a series of documents called By the Numbers. I felt a little bolder. I began putting asterisks or footnotes in the documents—not to refute what they said, but instead to just say what I saw. What this monolith of whiteness missed in their looking, in their telling. And bit, by bit, I became braver. The documents wanted to be concrete—they wanted to tell one official narrative. But when I wrote into them, I found that the story of the camp knew how to pry apart the cracks. Knew how to grow something more true and more beautiful.

My close friend and Water Protector, Kimimila Locke, reminds me often that the project of colonialism is to create disconnection. The state’s narrative asks us not to see joy, not to see tenderness, or care. They don’t see the children carrying bowls of soup to elders. They don’t see folks installing wood burning stoves or sorting endless boxes of donations or the long and laughing conversations by firelight. And the world is full of official documentation of this type—court filings or bad reporting or medical forms or political speeches. Words and numbers and boxes that don’t see, that choose not to see the butterflies rising from the prairie like mist.

I want these poems to chop the firewood. To be willing to stir the soup pot and chop the onions, and yes, even clean the porta potty. I think this space of care means, both seeing what the state is doing, and asserting what we know, what we see. In situations in which the story of people is being smothered by institutions of power, adversarial documents can provide an opening, a way to both see these narratives and simultaneously break them apart—to make space for the butterflies to rise, for the flowers to grow.

__________________________________

Something Small of How to See a River by Teresa Dzieglewicz is available from Tupelo Press.

Teresa Dzieglewicz

Teresa Dzieglewicz is an educator, poet, and part of the founding team of the Mní Wičhóni Nakíčižiŋ Wóuŋspe (Defenders of the Water School) on the Standing Rock Reservation. She was named a Best New Poet of 2018, as well as winner of the 2018 Auburn Witness Prize, a 2018 Pushcart Prize, and the 2020 Palette Poetry Prize. Dzieglewicz has been a fellow at New Harmony Writers Workshop, the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center, the NY Mills Arts Retreat, and Brooklyn Poets. She received her MFA from Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, where she was recognized with an Academy of American Poets Prize.