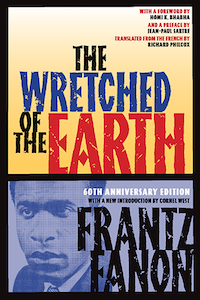

Cornel West on Frantz Fanon, One of the Great Revolutionary Intellectuals of the 20th Century

“Decolonization implies the urgent need to thoroughly challenge the colonial situation.”

Frantz Fanon is the greatest revolutionary intellectual of the mid-20th century. He also is the most relevant for the 21st century. His theoretical genius, literary artistry, and political courage are undeniable. And his personal integrity, wholesale honesty, and self-critical tenacity are indisputable. Like Charlie Parker’s bebop revolution in modern music, Frantz Fanon’s works and witness disrupted and shattered prevailing paradigms in modern philosophy, culture, and politics. Similar to Nina Simone’s subversive sonic intellect, Frantz Fanon made confronting the historical realities of decolonization inescapable. In short, he is a towering figure in our neo-liberal and neo-colonial time because he cast a light on the terrifying and terroristic underside of white supremacist European imperialism—a light that enables us to keep track of how those chickens have come home to roost around the world.

The Wretched of the Earth (1961) was Fanon’s last testament—at the tender age of 36—to his prophetic vocation. This calling was motivated by a profound love of colonized people and grounded in a deep love of the truth of their doings and sufferings. In the first moments of this perennial classic book, he writes, “decolonization, therefore, implies the urgent need to thoroughly challenge the colonial situation. Its definition can, if we want to describe it accurately, be summed up in the well-known words: ‘The last shall be first.’ Decolonization is verification of this.” His biblical allusion to Jesus (Matthew 20:16) and revolutionary declaration of a “murderous and decisive struggle” between the colonizer and colonized, occupier and occupied, makes us confront the naked violence and raw force of the asymmetric power of the dominating over the dominated. Fanon will not allow us to begin our discussion with the counter-violence of the oppressed, but rather with longstanding and often overlooked terror and trauma of the structural violence and everyday horror shot through the colonial realities for precious ordinary people.

When Fanon states, “the colonial world is a compartmentalized world,” he compels us to acknowledge colonialism is a sustained barbaric war waged against colonized people sanctioned by Western values. “Now it so happens that when the colonized hear a speech on Western culture they draw their machetes or at least check to see they are close to hand… In the period of decolonization the colonized masses thumb their noses at these very values, shower them with insults and vomit them up.” Fanon’s indictment of European colonialism is more than a fancy epistemic rejection of Eurocentrism or a mere Nietzschean moment of opposition against a dialectical vision of deliverance.

Similar to Nina Simone’s subversive sonic intellect, Frantz Fanon made confronting the historical realities of decolonization inescapable.

Rather, Fanon is deepening, refining, and “slightly stretching” Marxist analysis by wedding an unrelenting critique of predatory capitalism and its imperial tentacles with an Empire-driven analysis of a war-like white supremacy that permeates the very souls of colonial subjects as well as shapes every sphere of colonial society. Like a great jazz musician, Fanon enacts and embodies modes of counterpoint that creatively fuse Karl Marx’s critique of capitalist economies, Carl von Clausewitz’s philosophy of war (with Mao Zedong’s guerrilla warfare addition), François Tosquelles’s (and to some degree Jacques Lacan’s) rich notions of sociogeny and milieu therapy, and, above all, the inimitable examples of Aimé Césaire (Fanon’s teacher, mentor, and fellow Martiniquean freedom fighter) and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Fanon is first and foremost a revolutionary whose artistry in language, speech, and political praxis bids us to resist and overthrow all forms of dogma and domination that subjugate oppressed peoples. (Note his “final prayer” in Black Skin, White Masks [1952]: “O my body, always make me a man who questions!”). This intense Socratic energy—aligned with what he calls “African self-criticism”—yields a thoroughgoing internationalism that passes through a genuine national consciousness. “Self-awareness does not mean closing the door on communication. Philosophy teaches us on the contrary that it is its guarantee. National consciousness, which is not nationalism, is alone capable of giving us an international dimension… It is at the heart of national consciousness that international consciousness establishes itself and thrives.” Fanon’s revolutionary internationalism—like that of Karl Marx, C.L.R. James, Rosa Luxemburg, Ella Baker, Albizu Campos, B. R. Ambedkar, Emma Goldman, or his comrade Ali Shariati—never reduced the intellectual richness of European history solely to the vicious European crimes against humanity, especially against Third World peoples. He even goes further,

All the elements for a solution to the major problems of humanity existed at one time or another in European thought. But the Europeans did not act on the mission that was designated them…

The Third World must start over a new history of man which takes account of not only the occasional prodigious theses maintained by Europe but also its crimes…

Moreover, if we want to respond to the expectations of the Europeans we must not send them back a reflection, however ideal, of their society and their thought that periodically sickens even them.

For Europe, for ourselves and for humanity, comrades, we must make a new start, develop a new way of thinking, and endeavor to create a new man.

For Fanon, revolutionary internationalism—anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist, anti-colonialist, anti-patriarchal, and anti-white-supremacist—yields a new humanism that puts a premium on the psychic, social, and political needs of poor and working peoples—a solidarity and universality from below.

Women shall be given equal importance to men… in daily life, at the factory, in the schools, and in assemblies.

If the national government wants to be national it must govern by the people and for the people, for the disinherited and by the disinherited. No leader… can replace the will of the people, and the national government, before concerning itself with international prestige, must first restore dignity to all citizens, furnish their minds, fill their eyes with human things and develop a human landscape for the sake of its enlightened and sovereign inhabitants.

Yet Fanon’s revolutionary internationalism and new humanism were betrayed by new national bourgeoisies from every corner of the globe. In his famous and still highly relevant chapter, “The Trials and Tribulations of National Consciousness” (a favorite I recall in our intense discussions with Black Panther Party comrades in the 60s and 70s), he rightly predicted, the “fight for democracy against man’s oppression gradually emerges from a universalist, neoliberal confusion to arrive, sometimes laboriously, at a demand for nationhood.

But the unpreparedness of the elite, the lack of practical ties between them and the masses, their apathy, and, yes, their cowardice at the crucial moment in the struggle, are the cause of tragic trials and tribulations.” In our time—our Obama moment and its aftermath—this neoliberal tragic mishap has become a neoliberal fascist backlash. Big Money—Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and Big Tech (as well as Big Militarism), filtered through the Pentagon and State Department—is in the driver’s seat. Ugly white supremacy is the public face. And patriarchy, homophobia, and transphobia run amok.

Frantz Fanon is one of the few great revolutionary intellectuals who always connected the psychic and the political, the existential and the economic, the spiritual and the social.

The most well-known sentence in Fanon’s canonical work is the first line of “On National Culture”: “Each generation must discover its mission, fulfill it or betray it, in relative opacity.” Let it be said again—surely and strongly—that the national bourgeoisies of the past 60 years since Fanon’s book appeared have indeed betrayed their revolutionary mission. Their “neoliberal universalism” can no longer hide and conceal their capitulation to Big Money, Big Militarism—and political centrism. Furthermore, their levels of corruption, lack of accountability, greed, narcissism, and repression of those who threaten their power have trumped any fundamental transformation.

Fanon’s Algerian context led to his fascinating yet sometimes objectionable formulations about the revolutionary potential of the lumpenproletariat, the peasantry, or even the cathartic effect of armed struggle for colonized people. Yet his crucial claims about the need for strong mechanisms of accountability for leaders, the necessity of self-critical political education for citizens, and the civic institutions that attend to trauma and mental disorders are irrefutable. Like his teacher, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Frantz Fanon is one of the few great revolutionary intellectuals who always connected the psychic and the political, the existential and the economic, the spiritual and the social.

In our present-day moment of imperial decay and capitalist decrepitude (be it in the USA, China, or Russia)—including our ecological emergency, escalating neo-fascism, and pervasive xenophobia (against Muslims, Arabs, Jews, and LGBTQ+ peoples) as well as deep white supremacy—the spirit of Fanon is most manifest in my American imperialist context in the revolutionary internationalist wings of the Black Lives Matter movement and the Palestinian Lives Matter movement aligned with the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions efforts. Yet the task of full-fledged decolonization and wholesale democratization with genuine socialist options remains unfinished. Let us not betray our mission—just as Frantz Fanon never sold his soul nor betrayed his prophetic vocation!

__________________________________

From The Wretched of the Earth. Used with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press. Copyright © 1963 by Présence Africaine. English translation copyright © 2004 by Richard Philcox. Introduction copyright © 2021 by Cornel West. Foreword copyright © 2004 by Homi K. Bhabha. Preface copyright © 1961 by Jean-Paul Sartre. Originally published in the French language by François Maspero éditeur, Paris, France, under the title Les damnés de la terre, copyright © 1961 by François Maspero éditeur S.A.R.L. Revised 60th anniversary edition first published in October 2021.

Cornel West

Cornel West is a prominent and provocative democratic intellectual. He is Professor of the Practice of Public Philosophy at Harvard University and holds the title of Professor Emeritus at Princeton University. He has also taught at Union Theological Seminary, Yale, Harvard, and the University of Paris. Cornel West graduated Magna Cum Laude from Harvard in three years and obtained his M.A. and Ph.D. in Philosophy at Princeton. He has written 20 books and has edited 13. He is best known for his classics, Race Matters and Democracy Matters, and for his memoir, Brother West: Living and Loving Out Loud.