Constantine Cavafy: The Making of a Poet

Gregory Jusdanis and Peter Jeffreys on the Artistic Journey of Modern Greek Literature’s Most Distinguished Poetic Voice

“Voices”

Idealized, beloved voices

of those who have died or are

lost to us like the dead.

Sometimes they speak in our dreams;

and our mind hears them in our thoughts.

And with their echo for an instant

echoes of the first poetry in our lives come back like

music that fades into the distant night.

(1903/1904)

*

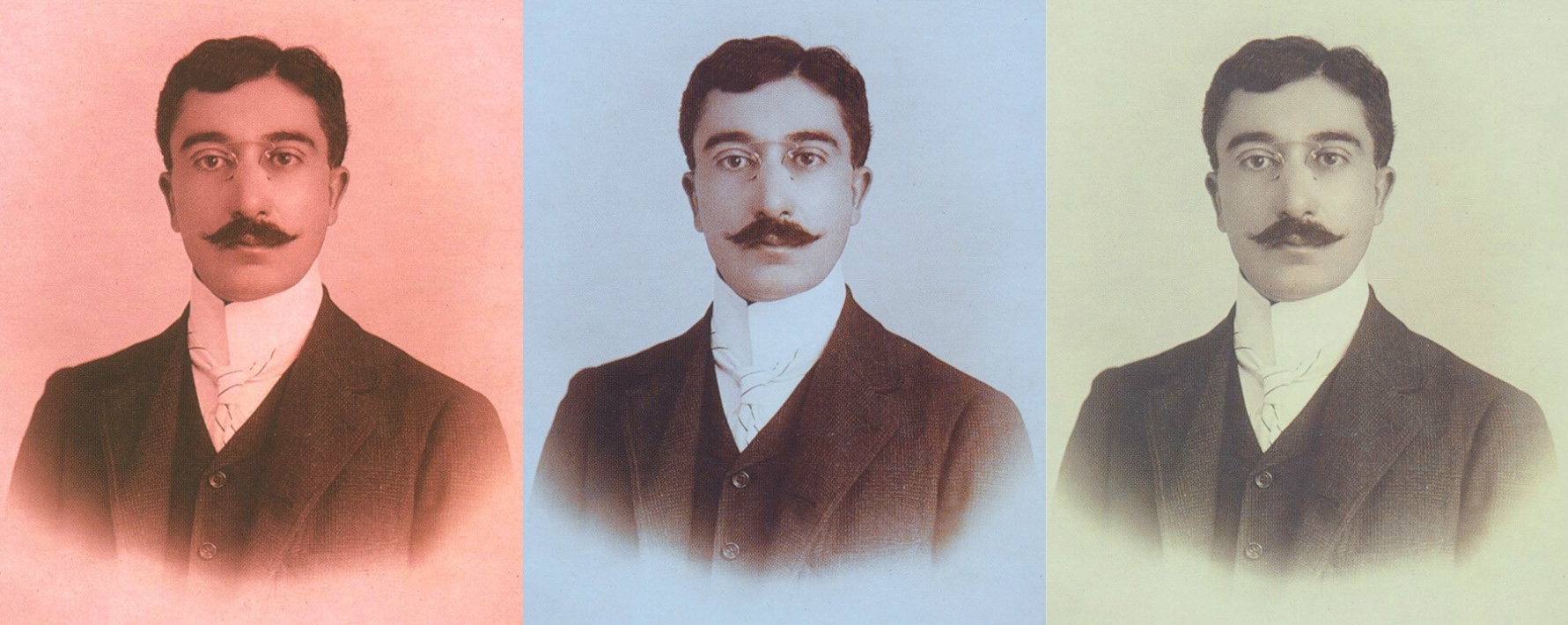

No one who knew Constantine as a young man in the 1880s and 1890s would have expected him to turn into a world poet. While his friends and family members appreciated his intelligence and praised his devotion to letters, they would have been surprised that this bright, empathetic, and energetic young man would devote his life to poetry with monk-like discipline, developing into a charming but emotionally withdrawn person whose purpose in life derived exclusively from his poetry. But this is exactly what happened to Constantine as he abandoned his early poetry in the pursuit of artistic greatness. Poetry would become his life and he would live for poetry.

Constantine transformed himself into an artist twice, first in his twenties and then again in middle age. During this second period, Constantine became the poet we know as Cavafy. He remained a bit defensive about his relatively late poetic maturation. He resented, for instance, that Michalis Peridis said in 1915 that Constantine at fifty-two had nothing more to say and that his life’s work had been completed. “Many wrote after their forties,” Constantine said in response: “The great Anatole France wrote his colossal work after turning forty-five. And many others.”

It took Constantine a few decades to free himself from the weight of this tradition, even though there survived, in both his poetry and his speech, traces of the purist language.

Constantine’s early poems, those he repudiated in middle age, revealed little promise of future greatness. While poets like Arthur Rimbaud and George Seferis distinguished themselves with their first collections, Constantine’s initial publications struck few as innovative. They showed little sign of his Promethean ambition or his looming struggle against contemporary poets and the titans of the past. Moreover, these early texts were derivative, reflecting the tastes and aesthetic properties of the Greek poetry he was reading in his youth, as explained in the previous chapter. Eventually he came to see this poetry as cold and rhetorical, heavy in katharevousa and laden with tropes of romantic love, nature’s beauty, and the Greek nation, subjects he would come to abhor in his middle age. It took Constantine a few decades to free himself from the weight of this tradition, even though there survived, in both his poetry and his speech, traces of the purist language.

We don’t know exactly when he began writing his first poems. But in a note written in 1906, he disparaged “the wretched trash” he had written between the ages of nineteen and twenty-two. So it is safe to assume that he embarked upon his first ventures into literature while he was in Istanbul. In his letters to his brother John from this city, Constantine demonstrated an acute interest in words, their meaning and place in a sentence. He had begun compiling a dictionary in 1881 precociously at the age of sixteen, which ended with the entry “Alexander.” To his horror, it was one of the items destroyed in the bombardment of 1882. He referred anxiously in his letters to John about his papers back home, only to receive the reply that all was lost. “It is one of the talents of great stylists,” Constantine wrote much later in 1902, “to make obsolete words cease from appearing obsolete through the way in which they introduce them in their writing.” He might have been thinking here of his aborted lexicographical project.

Contemporaries often reported his near fixation on matters of diction, punctuation, and even spacing in his verses. For instance, when he and a group of young men were discussing a nineteenth-century English poet, Constantine began a meandering passage through the “labyrinth of metrical subtleties.” At one point, one of the visitors intervened: “Certainly, maître, all of these are details,” to which Constantine responded vehemently, “What else is art but details.” As he said in his poem “Of Colored Glass,” “I am much moved by a detail.” The editor, critic, and friend Giorgos Papoutsakis claimed that, although Constantine had crafted his own innovative poetry, he never abandoned his “devotion to the choice of words.”

Indeed, Papoutsakis remembers him saying around 1931 that the “majority of Greek poets have not given sufficient attention in their work to the issue of lexical exactness [kyriolexia].” To achieve this expressive precision, Constantine carefully worked on poems, polishing each and every word sometimes for close to fifteen years before sending them to the printers. He began “Orophernis,” for instance, in 1904 and kept working on it until 1916.

Despite the exhilarating exposure to Greek poetry, journalism, and critical thinking he encountered in the Greek community of Istanbul, Constantine was not happy to be away from his own books and manuscripts and expressed uncertainties about his own talents. For this reason, John, trying to encourage him, lauded his brother’s well-written letter, adding that he would “very soon outlimit my knowledge of the [English] language” (January 16, 1883). This was a very generous comment given his own ambitions for fame, especially in writing an experimental poem in the manner of the French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé (1842-98) totaling four thousand lines. John’s literary talents were evident in his letters, some of which he even composed in verse: “I’ll answer yours of twenty-nine / October, not in prose but ‘worse.’ / The Muse directs ecstatic verse, / The thoughts are hers,—the rhymes are mine” (November 7, 1882).

Of course, John too suffered from insecurity, stemming perhaps from the comparisons he made between himself and Constantine: “I lack your versatility of genius and the power to give interest to a mere nothing” (January 16, 1883). In the following letter, John expressed doubts about his own “poetical talents (for such you will have them), they are, I am sorry to say, of the ‘touch-and-go’ nature. No man is the same under all circumstances; and least your humble servant, who is subject, in the highest degree, to outward objects and the inclemency of the winds” (January 23, 1883). He would later confess that he was not able to write at all: “My poetical vein is at present desultory and spasmodical [sic]: I have not much leisure time” (June 5, 1883). By characterizing his efforts to write poetry as “desultory” and “spasmodic,” was John implying that his poetic career was coming to an end?

Whatever his feelings at the time, the publication in Alexandria of his Early Verses made no stir. Sadly, this was the only book he published and eventually he stopped seeing himself as a poet. Around 1890-91, he printed a few poems like “Pygmalion Meditateth” as loose sheets, which he later published in Rivista Quindicinale. But that was it. Toward the end of his life, John cast himself largely as a flop. But he remained proud of Constantine and how hard he worked to make his name known among his small circle of friends and acquaintances. Outwardly there seems to have existed no overt competition between them, given that they were nearly two years apart and each possessed grand artistic ambitions. But one wonders if John ever begrudged his brother’s surpassing him as a poet.

John’s failure could not but have stood to Constantine as a fate he had to avoid. If we look at a couple of John’s verses, we can see how derivative they are in versification and subject matter, resembling Constantine’s early poems that he eventually disowned. The first stanza of “Pygmalion Meditateth” begins with the following lines: “My poem! It shall be a paradigm, / In marble cadence, of the beautiful, / And therefore true,—perfect in every limb.” And it ends with the lines “And so I rise; My poem shall express / The beautiful in marble cadences.” Unfortunately for John, these poems did not “rise” at all. In their meter, diction, and themes, they were thoroughly Victorian. No wonder they found no audience, no critics, and no appeal, a silence Constantine could not have failed to notice. He could see that John’s work was old-fashioned and unexceptional. It was not, in other words, the type of poetry that could change the “minds of millions,” as he hoped to do himself.

In addition to thinking about how to escape John’s imitative poetry and scholasticism, Constantine had to consider his own future. What was he going to do when he and his mother returned from Istanbul? During his stay in the Ottoman capital, he thought about a career in political journalism. We surmise this from a letter (November 22, 1883) his godmother and paternal cousin, Amalia Pitaridou-Papou, wrote from Athens in response to his own, which does not survive and which probably sought advice about his career plans. She cautioned him that “success in politics requires studies in law…and neither is journalism appropriate for you.” Young men nowadays, she continued, went increasingly into banking or business and she encouraged him to pursue this line of work. It appears also that Constantine expressed his desire to write poetry, for she continued, “From your letter I understand that you have an inclination for poetry and I am sure that Constantinople with its beautiful nature can inspire you.” This well-meaning but innocuous piece of advice demonstrates that his family did not really understand poetry at all beyond these rudimentary parameters.

When Constantine arrived home in October 1885 at the age of twenty-two, he had few prospects for work and for many years held no firm job, a situation that forced him to rely on his mother for financial support and one that could hardly continue given the family’s ever-dire financial circumstances. Yet he was not destined for professional life, certainly not in the cotton business that attracted talented young Greeks. Like many men in their twenties, he was in search of gainful employment without however possessing a particular purpose. One possibility was to engage in journalism, as he had told his aunt. Publicly at least he thought of himself as a journalist, having written, as noted earlier, his first piece (1882) on the poet Athanasios Christopoulos the year the British fleet bombarded Alexandria. So with all the other brothers gainfully employed, Constantine began to work at the Bourse in 1886 as a journalist for the newspaper Telegraphos.

As stimulating as it must have been to breathe in the competitive air of the exchange, he never saw himself as a financial reporter. Thus, he returned to his real love—literary and cultural criticism. He wrote many critical essays both in katharevousa and in English, most of which remained unpublished. A few dealt with political issues, such as the Cyprus question and the return of the Parthenon marbles. While he demonstrated some talent as a book reviewer, translator, and cultural critic, he abandoned the idea of becoming a professional journalist by 1897. Yet for most of the 1890s, he did not present himself exclusively and publicly as a poet either, even though it was a very productive decade for him poetically.

Increasingly he was turning his energy toward poetry, and he was thrilled when his first poem, “Bacchic,” appeared in the Leipzig periodical Hesperus in 1886. This was no doubt a great accomplishment for a young man of twenty-three living in provincial Alexandria. Yet his first little triumph, inspired by the Phanariot poet Athanasios Christopoulos (1772-1847), gave little impression of the demoticist revolution taking place in Greek poetry at the time, namely that poets were turning to the vernacular as their medium of expression. He went on to publish a series of poems in katharevousa, with titles like “The Poet and the Muse” (1886), “Builders” (1891), and “Voice from the Sea” (1898).

From now on attention would fall on his poetic creations, an increasing focus that brought with it greater public recognition but also distance from those dear to him.

At this time, he also embarked on many other intellectual ventures. In 1891, as a carryover from his aborted dictionary project, he began work on a lexicon—a dictionary of citations. Although it did not seem like a long-term venture then, it would develop into one over time. As he wrote in a draft introduction to this work many years later, he had been using a very good Greek dictionary (without identifying it), which had many more demotic entries than others he had consulted. (He would refer to at least thirteen dictionaries when compiling his catalogue of citations.)

But this book had many shortcomings. For this reason, he thought it would be useful to supplement it with his own entries. Thus, during his readings, whenever he encountered a “beautiful or expressive word,” demotic mostly but also in purist and ancient registers, he would record it along with the citation and then place the piece of paper in the appropriate page of the dictionary. After a number of years, these entries began to slip out of the volume, so he decided to record them in a notebook “for my own personal use or for the use—if they wanted—of my friends.” Not burdensome at all, this work seemed rather “pleasurable.” But he collected these words primarily because they were useful to him “as an author,” by which he meant a poet. In other words, he pursued this project as a personal resource rather than as a linguistic venture to be published in the form of a book. Some of the words he selected seemed predictable and many were gleaned from his reading of Greek poetry and folk songs. Others showed his linguistic curiosity. Thus, we have entries for the word “vampire,” and for the Greek aperitif “ouzo” with its two variants (tsipouro and zibib).

When he ended the project around 1917—that is, nearly thirty years later—he had assembled some 561 entries that collectively constituted a book. Even though he never published it, he showed himself an accomplished lexicographer with a zeal for both the Greek language and an exactitude for expression. Not trained as a linguist, he certainly could have become one, as he could similarly have developed his penchant for history by turning into a historian. This intellectual prowess and range were a mark of his genius and illustrate that, without any university education, he possessed a scholarly knowledge of the Greek language and of Greek history that impressed professional linguists and historians alike.

About two years after he started his dictionary of citations, he developed another useful tool for his poetic craft, a Rimario (rhyming dictionary). Written on paper from the Office of the Irrigation Service and following the example of other poets in the nineteenth century, he compiled lists of rhymes that he culled from various dictionaries. In 1897/98, he began a second catalogue of rhymes he himself gathered from the poets he read. He relied on these two catalogues when composing his poems, and it is possible to identify eighteen of these rhymes in his poems. They were less useful to him after 1900, however, when his poetry relied less on rhyme.

Constantine’s primary focus, if not fanatical preoccupation, from 1890 on was poetry. While his family and friends did not see the results of his creative labor in published poems, he recorded the titles of 131 new poems in his catalogue between August 1891 and December 1898. Between January 1899 and December 1903, he listed thirty-two, of which nine were previous drafts.

In the following year, his records indicate twenty-seven compositions, the only one of which that survived being the famous “Candles,” published in 1899. Dealing with old age, it is an unlikely topic for a man of thirty. The speaker stares at a row of candles representing his life and is distressed at the sight of the long row of snuffed-out wicks: “I don’t want to look at them; their sight saddens me, / I am saddened also to remember their previous light. / I look ahead at my lit candles.” Constantine was so pleased with this poem that he wrote about it to Pericles Anastasiades, saying that this was “one of the best things” he had ever written. He repeated his sense of pride to John, who at that time was rendering it into English, characterizing it as “good” and easy “for translation.” This three-page draft of a note, composed sometime between 1897 and 1899, reveals how sophisticated his aesthetic theory had become by then. Although the poem appeared to him slightly allegorical, Constantine continued, it was actually “dramatic” and thus different from “Walls” and “The Windows,” poems that were “clearly allegorical.”

What is striking about the text, however, is not only the maturity of his poetics but also his own self-confidence as a poet. He was no longer beholden to John for advice and guidance and, in fact, reversed the power dynamic of their relationship. In contrast to their correspondence in the early 1880s about John’s poetry, in which the older brother seemed to be in command, here the situation was the opposite. In the 1880s, John appeared destined for poetic glory and Constantine’s deferential posture tacitly accepted this outcome.

By the end of the decade, however, Constantine had overtaken his brother as the artist of the family. From now on attention would fall on his poetic creations, an increasing focus that brought with it greater public recognition but also distance from those dear to him.

__________________________________

From Constantine Cavafy: A New Biography by Gregory Jusdanis and Peter Jeffreys. Copyright © 2025. Available from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, an imprint of Macmillan.

Gregory Jusdanis and Peter Jeffreys

A Distinguished Arts and Sciences Professor at the Ohio State University, Gregory Jusdanis is the author of The Poetics of Cavafy, Belated Modernity and Aesthetic Culture, The Necessary Nation, Fiction Agonistes, and A Tremendous Thing. He has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Peter Jeffreys is an associate professor of English at Suffolk University in Boston and has written, translated, and edited a number of books about and by Cavafy: Eastern Questions: Hellenism and Orientalism in the Writings of E. M. Forster and C. P. Cavafy; The Forster– Cavafy Letters: Friends at a Slight Angle; C. P. Cavafy: Selected Prose Works; Reframing Decadence: C. P. Cavafy’s Imaginary Portraits; and Approaches to Teaching the Works of C. P. Cavafy. He is a member of the Cavafy Archive Academic Committee at the Onassis Foundation and has served as an exhibition consultant for the Cavafy House in Alexandria and the Cavafy Archive Building in Athens.