It was difficult to be me in 2007. I was, to my disappointment, much shorter than the average height. Our finances forced my parents to choose between a pediatrician and a dentist, which meant that I never got braces to correct the space between my front teeth or my right-side snaggletooth. I was desperately addicted to the internet, from the edgelording of 4Chan to the privilege-checking of Tumblr (though we didn’t have names for edge-lording or privilege-checking back then) to the unremitting capitalism of YouTube (we’ve always had a name for that). I made very little eye contact, preferring instead to study the textures of the ground and my shoes. This wasn’t because I was shy—I actually could start a conversation with anyone willing to talk to me—but because my eyesight was so bad that at seventeen, I was halfway to being legally blind, and making eye contact meant showing whomever I was looking at the disturbing degree to which the lenses of my glasses magnified my eyes. The glasses were the worst thing about me, possibly the worst thing about anyone. I had begun wearing them at age two, and my eyesight had deteriorated in the intervening fifteen years so that I had 20/100 vision by the time I was a junior in high school and reading was only possible with bifocals. Pretty girls in ribboned pigtails and Aéropostale approached me in the hallway, asking with polite concern how I’d done on some trigonometry quiz or AP US history test. They did this as if being kind to me would guarantee them entry into a top-tier college. I told them—truthfully—that I’d received a 98 or 99 (I’d always received a 98 or 99), which infuriated them. I wasn’t supposed to be self-sufficient, and I certainly wasn’t supposed to be capable of outperforming them.

Things got worse when I arrived at Last Chance Camp, where even the younger prisoners towered over me, muscular, shadow jawed. The camp, which was really called Wellspring, was run by a former pastor, an ex–Navy SEAL, and a group of early-twenties “counselors” who were supposed to discipline us by forcing us to do hard work. It was located on a farm in rural Colorado, on land we cultivated by ourselves with only shovels and hoes as though we were medieval serfs. We would be awakened at 5:00 in the morning by the ex–Navy SEAL blaring a police siren from his Honda Civic as he drove down the gravel road behind our cabins. Then a lucky quarter of us would be placed on mess duty, making breakfast while the rest of us performed “inspection,” which meant cleaning every inch of every cabin and standing outside while the former pastor and the ex–Navy SEAL inspected each of them. Both the former pastor’s and the ex–Navy SEAL’s names were Doug, so we referred to them by their last names: Mr. Kimborough (the former pastor) and Mr. Sledge (the ex–Navy SEAL). Kimborough would sometimes compliment us on our cleaning, but Sledge always found something out of place, some crumb or pocket of dust untouched by our washcloths and brooms, and for these small errors he would make us run three times around the entire property. This happened so often that I couldn’t remember going to breakfast not sweating, too hot and dizzy to eat whatever warm mash those on mess duty had prepared. We would be worked so hard for the rest of the day that I should have had an appetite, but I never did. I typically ate a boiled egg or a rock-hard potato for lunch, and then I choked down half of whatever protein-rich mash was being served for dinner. Being rotated onto mess duty didn’t help the problem, either, because I didn’t know how to cook—no one did, really. I lost twenty pounds I didn’t have to spare.

Last Chance Camp was supposed to be the final stop before juvie, but its price tag suggested that whoever went there had parents who could pay their way out of juvie. The cost was prohibitive for my family, but my dad insisted I apply for a scholarship after the incident. I tried to tank the essay but I was required to submit my transcripts, and there was no way to pretend that I didn’t have a near-perfect GPA. This was because the material in high school was easy to master without taking notes or spending more than ten minutes glancing over a textbook. I was able to quickly diagnose each teacher’s particular brand of laziness. If they were enamored of their own cults of personality, they’d assign massive tests that were worth half the grade. If they were timid and bored, they’d assign frequent quizzes that someone with a memory worse than mine might have needed to study for. And if they were bitter about their unglamorous work, as most of them were, they arranged the class so they’d have to do as little grading as possible: one big project that was easily bullshit-able, one big test that there was no need to study for. Last Chance awarded me a full scholarship, much to my horror and disappointment.

I landed at Last Chance because of a hustle. My family lived in an apartment on the border of a wealthy school district, and my parents had lobbied to let me attend the wealthy school instead of the overheated, overcrowded, and understaffed public school in our district. I was granted access to the kingdom, which meant that I was the only student wearing shirts with too-short sleeves, carrying a backpack with frayed straps, entirely without a car or a good-looking cell phone. I biked the five miles to school because the bus was a moving shark tank: if I was cornered, there would be no escape. I wanted at least half an hour of peace before I was surrounded at the school, shoved, elbowed, stared at. I ate alone in the cafeteria and was frequently the object of pity for kids of moderate social standing who had been taught by their liberal parents to mime empathy. They were worse than the Aéropostale girls because they thought they were being charitable. “Do you want my sandwich? Do you need me to buy you some milk?”

One day, I bought a $10 pair of white sneakers from the bottom of the clearance bin at the Payless in the mall. I brought them home, took my mom’s sewing kit from its place in the utility cabinet we’d dedicated to everything we didn’t have space for: a wrench, a discolored plunger, tattered washcloths. As my parents slept, I stitched the sneakers up to look like Adidases. It wasn’t as difficult as I thought it would be: I’d been coveting other people’s Adidases my entire life, and I had a surprisingly steady hand. This took several nights, and when they were finished, I wore them to school. I drew looks in the hallway and cafeteria and pretended to be oblivious to them. I ate the bologna and cheese sandwich my mom had packed for me and stared ahead as Hayden Pritzker and his friends swarmed around me.

“Hey, bruh,” Hayden said. He was white but desperately wanted to be Black.

I looked up as though I’d just noticed him. He was flanked by Tyler Scarpone and Nick DeQuist, both of whom drove SUVs to school.

“Those shoes are tight as hell,” Hayden said.

I looked from my shoes to Hayden to my shoes again. “They’re limited edition,” I said. “Like not in stores yet. I know a guy.”

“How much they cost?”

I took a moment to think of a realistic number. “Three-fifty.”

The three of them exchanged looks. That I should be wearing a pair of

$350 shoes made little sense to them, but there I was, wearing them. The fact couldn’t be questioned. Neither could it be questioned that they wanted them.

“So you have a hookup?” Tyler asked. I nodded.

I had saved up $100 doing yardwork over the summer, which I then spent on ten pairs of white Payless sneakers. I spent a month stitching these sneakers up. I told Hayden that my connect was “laying low” in Hawaii, and that he’d hit me up the minute he got back. At the end of the month, I sold Hayden, Tommy, and Nick three pairs for the discount price of $300. I sold the rest to their friends.

“What else your hookup got?” Hayden lisped through his fake grill.

My hookup had XiX, the perfect blend of coke and molly that was really just my dad’s ground-up Sudafed and sea salt. XiX sold for $40 an eighth and $75 a fourth. Hayden bought a fourth from me and invited me to his party, where he said he and his friends planned to snort the entire bag. I respectfully declined, making up some pressing homework assignment, and Hayden shrugged and said, “You still cool, man.” The next night, a Saturday, he texted me: i’m hallucinating off this shit!!! I texted back: just do little pinkie bumps.

I told my parents that I’d picked up some “odd jobs” after school, raking the leaves and cleaning the gutters of families richer than us. What I really did was ride my bike to Hayden’s neighborhood and look at the towering McMansions there, the lawn crews mowing grass and trimming hedges, the children speeding down the streets on Vespas. I rode down every street and around every cul-de-sac several times, waiting for an hour to pass until I could return home and give my parents $100. My dad was agog. He wanted to know how I’d made that much in a single afternoon.

I shrugged. “They tip well in that neighborhood,” I said.

After a year of Adidases and XiX, I’d made $2,500, which I gave to my parents in installments of $100 and $200. No suspicion from administrators, who were too checked out to care about anything we were doing. I stressed that everyone take XiX in the smallest amounts possible—it was so potent—and because I’d become “that guy,” people listened to me. Except for Jordan Pinkerton, who was desperate to impress her boyfriend, a soccer player who’d won a scholarship to Harvard and was known for being able to drink anyone under the table.

I was in gym class with Jordan on the day it happened. We all had to change into uniforms that were our school colors, the T-shirts gray and the mesh shorts primary blue. I had sold Jordan an eighth of XiX the night before, and she looked dazed. She may have been doing bumps or even lines throughout the school day, possibly to convince her boyfriend that she was as hard-core as he was. As we ran laps around the gym, I considered breaking out of our lackluster formation and asking her if she was all right. This was the first time that I thought I might have crossed a line, that these people who had so much more than me were still human. It was in that moment that Jordan developed a raging nosebleed. She stopped running, saw the blood forming dark crimson dots on her gym shirt, and fainted on the spot. When she woke up, she told the principal where she’d gotten the XiX. I was expelled. The Pinkertons agreed not to press charges on the provision that I served some sort of time, be it in juvie or somewhere else that would “straighten me out.” And so I spent my summer at Last Chance.

__________________________________

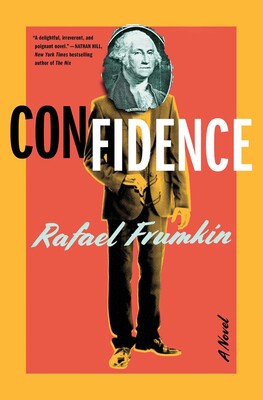

From Confidence: A Novel by Rafael Frumkin. Copyright © 2023 by Rafael Frumkin. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.