Confessions of an Undercover Novelist

Abigail Hing Wen on Difficult Family Conversations

For years, I kept my writing a secret from my family.

I am a dreamer. Out of necessity, my parents are practical people.

My dad left Indonesia for the United States at thirteen. As the eldest son of a poor family, he was sent to find a better life for his six siblings, a charge he’s taken seriously his entire life. My mom’s father had taken his college money and left China to start a cement company in the Philippines. My maternal grandparents passed away when my mom was only seventeen, and she soon fled for the United States in search of a better life as well.

Our childhoods couldn’t have been more different. Not only had they grown up in different countries and cultures, they came from business families. My parents had read perhaps one of the English and American novels my sister and I discovered in our school libraries. They were even less familiar with the games we played and the television shows we watched. They were focused on vitamins, dental appointments, car insurance—or at least, it seemed that way to me.

As a result, I shared more of myself—favorite books, crushes, hopes—with my friends than I did them. While I admired Laura Ingalls and dreamed about writing stories like her, I never shared that with anyone, let alone my family.

My parents wanted me to go into politics and give the community a voice. In their spare time, they were local community activists who went to bat for underdogs around them. I remember them meeting with my high school administrators, not for me or my siblings, but for an immigrant boy in trouble. They helped translate across cultures.

As for me, I tried to fulfill their dream. I interned for a US Senator and worked for a Presidential exploratory campaign. I went to law school and started down the path to becoming a professor. But while on maternity leave, I did something I had never done before.

I began to write a novel.

I wrote while I breastfed, and I wrote instead of sleeping, and, when my husband and I moved from DC to California to be closer to family, I stayed under the radar a few years to raise my boys and continue to write. I found critique partners and kept writing, more novels, getting feedback and getting rejected, never telling my parents what I was so busy doing with my limited spare time.

But several years into my secret writing habit, my siblings accidentally outed me. One day my mom and dad asked me with wrinkled-brow confusion, “Achi,” which means “big sister” in Hokkien, “Are you writing a book? About what?”

I printed out my novel and gave it to my dad. I redacted the intimate scenes for good measure. And I gave him a practical reason to read it: “Can you check the Mandarin?”

I played it down. It was my heart, and I couldn’t share it. Not with them. Not yet. I had enrolled in an MFA program in writing, a degree that would cost more than I’d made in my first years out of college. That math, to them, would simply be irresponsible.

When I returned home from the Vermont College of Fine Arts, my mom picked me up from the airport. I wasn’t expecting her—I hadn’t even wanted her to know I was traveling for a writing program. But she’d found out somehow.

As we pulled from the curb, she said exactly what I’d feared, “You shouldn’t waste so much money.”

But a few weeks later, she surprised me. She’d come over to drop off a pot of Adobo chicken, my favorite Filipino dish.

“I told my dad I would write a book about our family,” she said. “Maybe you’ll write it instead.”

That was the end of that conversation, but it was also a beginning. She was a storyteller, too—I’d grown up entertained by her tales of her twelve brothers and sisters, her rags-to-riches father, never fully appreciating what it meant to her to lose the protection and love of her parents at such a young age, and how far she’d come in her own fight for gender equality.

That moment brought it home for me. It gave me a surprising window into a part of her I hadn’t known existed. It made me a little less guarded about my own aspirations.

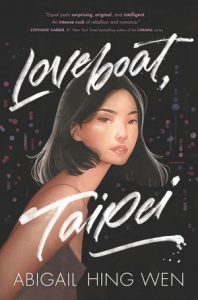

After I sold my first novel, Loveboat, Taipei, I went to my parents’ house for our holiday dinner. They’d gotten wind of the book deal from my brother.

My mom hugged me, her face glowing.

“You got a million dollars?” she exclaimed.

“Um, no, Mom.” I pulled back slightly. “I didn’t get a million dollars.”

“Oh,” she said, crestfallen.

At an earlier time, I might’ve felt let down, but this time, I laughed. Her aspirations for me in writing, it seemed, were even greater than my own.

They wanted to read my novel, of course. But my book had a girl with big dreams. It had romance: four love triangles. It even had sex and I still had yet to watch a kissing scene on television with my dad without him changing the channel.

But it felt like the right thing to do. I printed out my novel and gave it to my dad. I redacted the intimate scenes for good measure. And I gave him a practical reason to read it: “Can you check the Mandarin?”

He read the book in a few days, gave me feedback on the Mandarin, and translated the story for my mom. We haven’t spoken about its themes in depth—the topics are still delicate ones between us. But they’re my biggest supporters now. Their practical business advice is coming in handy as I go to launch.

Best of all, my book continues to unlock more stories from their lives. My dad as a college student, it turns out, used to drive two hours to buy Chinese groceries, then resold them at cost to his fellow classmates, just so they could all have a taste of home. In his own ways, I’m discovering, he’s a dreamer, too. They both had to be, to have taken the chances they took on America. Maybe in the same way I hid behind the practical “Can you check the Mandarin?” they’ve hidden behind the practicality of vitamins and dental appointments.

I’m no longer writing in secret. I’m talking to them about my ideas, even picking their brains for their experiences in Asia. I’m no longer dreaming alone.

And now, armed with their practicality, hand in hand, maybe we’ll be able to fulfill some dreams together.

__________________________________

Loveboat, Taipei is available January 7, 2020 from HarperCollins.

Abigail Hing Wen

Abigail Hing Wen holds a BA from Harvard and a JD from Columbia. She also earned her Master of Fine Arts in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Like Ever, she is obsessed with musicals. When she’s not writing stories or listening to her favorite score, she is busy working in venture capital and artificial intelligence in Silicon Valley, where she lives with her husband and two sons. Loveboat, Taipei is her first novel. Visit AbigailHingWen.com.