In the late 1970s, I stumbled upon an old, long abandoned, Oliver typewriter stored away in the back room of a typewriter repair shop where I worked in New York City. The Oliver was unlike anything I had ever seen: an odd-shaped, green-colored monster with three rows of keys and typebars—U-shaped metal rods with type attached to them—positioned high above its carriage. It was old and deserving of greater appreciation than it was receiving there. It begged me to rescue it from that dark room—and potentially the trash heap. So, I packed up the 30-pound orphan and carried it home on the subway during my standing-room-only rush-hour commute.

Once home, I began to explore this beauty a little further. The Oliver opened a door to a new world for me, one that ignited my curiosity about the early history of the typewriter. Before this point, I had never given a thought to the early days of the typewriter industry. Back then, interest in old typewriters was almost nonexistent and most machines were disposed of at the end of their useful lives.

Odell’s Type Writer (First Model), 1887

Odell’s Type Writer (First Model), 1887

Shortly after the Oliver discovery, I was leafing through the classified section of a monthly typewriter trade magazine when another vintage machine caught my eye: a Blickensderfer typewriter from the 1890s was being offered for sale. The Blickensderfer was a small manual typewriter that used a type element similar to the modern IBM Selectric typewriters that were popular in the 1970s. It was so much like the modern Selectric that I was repairing for a living back then, yet the 75 years that separated them made me curious about its history. There was so little information available on old typewriters at that time, so I acted on instinct, and I took a road trip across two states to purchase and pick up my prize. After all, I thought to myself, when would I ever see another one? On my return trip, a voice inside kept telling me that not only had I just acquired something special, but also, on that day, I had become a collector.

I went on a buying spree for the next few decades, searching for and acquiring as many interesting typewriters as I could track down. From flea markets, to auction houses, to estate sales, I crisscrossed the country in search of elusive machines. I believed anything could be anywhere and searched almost everywhere. In forty years of collecting, my only regrets are for the ones I didn’t buy, the ones that got away.

When I first became interested in vintage typewriters, collecting them was not a popular hobby. Finding another typewriter collector was almost as difficult as finding the actual machines. But over the past few years, there has been a resurgence of interest in mechanical typewriters—a renaissance of sorts. An object that had been deemed useless after the emergence of computers and relegated to the junk pile is now being celebrated. This revival seems to be both a combination of nostalgia and a desire to escape from modern technology. Unlike a computer, with all its word processing strengths and amenities, the typewriter offers a straightforward approach to the task of typing. A typewritten document isn’t merely typed, it’s created. Each key depressed immediately becomes a permanent imprint on paper. Mistakes are not easily removed, generating a greater need for concentration and requiring an undistracted, direct connection with the hardware responsible for producing a document. Driven by the force of the creator’s own fingers, and coupled with the unique characteristics of the machine being used, every document produced has its own personality and charm.

The Sholes & Glidden Type Writer, 1874

The Sholes & Glidden Type Writer, 1874

Some remained faithful to their typewriters during a period of technological change that began in the 1980s with the introduction of the personal computer. They were the holdouts who refused to part with their trusted friend as technology marched forward, always keeping a place on their desks for tasks that a typewriter could perform more efficiently than their computer. For these people, the filling in of forms, addressing of envelopes, and other small tasks always seemed to get done more quickly on a typewriter, giving the machines an extended life as a secondary writing instrument in many offices.

And then there are the collectors who see beauty in old, twisted, and often rusted metal. It is not uncommon for a dedicated collector to travel great distances to procure an ancient typewriter for his or her collection. Filling basements, attics, and storage sheds with these old unwanted relics is routine for typewriter collectors on their quest to assemble a collection and research the typewriter’s past. Some collectors have glass showcases in their homes to display the aristocrats in their collections. “History preserved,” as it is often said.

All the machines pictured here are from my personal collection in Garden City, New York. So many of us have a typewriter story to tell—whether we used the machines for papers in high school and college, or watched our grandparents type out letters on their cherished machines—stories that evoke fond memories of a much simpler time.

Anderson’s Shorthand Typewriter, 1889

Anderson’s Shorthand Typewriter, 1889

The Simplex, 1892

The Simplex, 1892

Bar-Lock No. 4, 1895

Bar-Lock No. 4, 1895

The Oliver (No. 1), 1896

The Oliver (No. 1), 1896

Sholes Visible, 1899

Sholes Visible, 1899

Underwood Standard Portable, 1919

Underwood Standard Portable, 1919

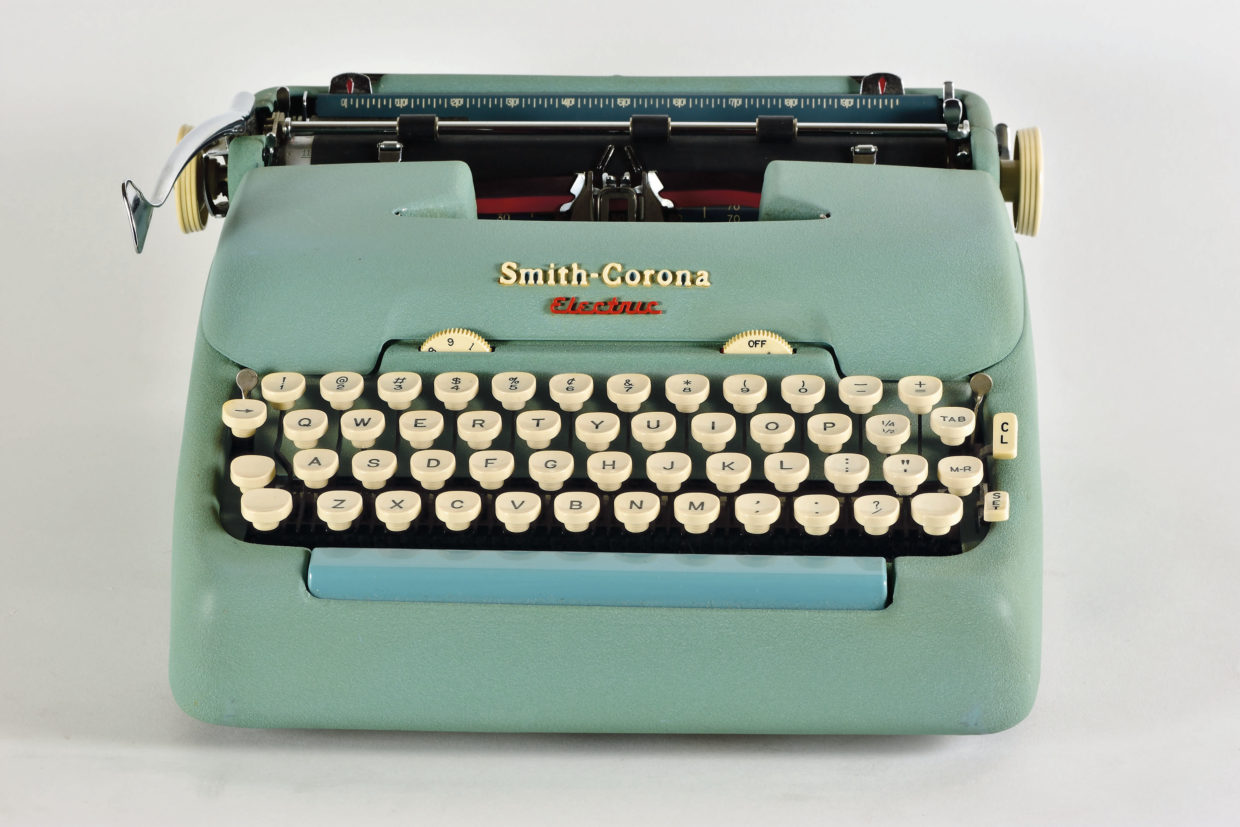

Smith-Corona Electric Portable, 1957

Smith-Corona Electric Portable, 1957

All photographs by Bruce Curtis and Anthony Casillo.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Typewriters: Iconic Machines from the Golden Age of Mechanical Writing by Anthony Casillo, published by Chronicle Books 2017.